Atkins’s work is emblematic of a tension in our culture’s current view of what it means to be human

Sometimes artists are diagnosticians of their time, sometimes they are symptoms of it. Over 15 years, Ed Atkins’s videos have offered an acute, often painful manifestation of how the human body, and the human subject it contains, has become a site of uncertainty – a question, or a problem. Atkins’s work is emblematic of a tension in our culture’s current view of what it means to be human, or at least where that meaning might still dwell, after all those old philosophical and existential reassurances – of religion or humanism or romanticism – have been stripped away. Once they’re gone, with what are we left? Maybe just meat-sacks, wired up to the artificial stimulus of images.

Before we get to Atkins’s turn to the use of CGI and motion-captured avatars, the show opens with early works Death Mask II: the Scent and Cur (both 2010), in which the artist sets up some abiding preoccupations; Death Mask is a circling sequence of up-close frame-filling objects, against a black ground, gaudy and enhanced like pumped-up stock imagery: a candle caught in a kaleidoscope lens, the back of a blonde head lit in hot pinks; what might be a watermelon or other round fruit. These are set to a soundtrack that mixes smooth artifice and its opposite – crackling analogue synth, rustles, half-finished sentences, microphone bumps, background noise – punctuated by the recurring, luridly overcoloured shot of a piece of old consumer tech – a silvery little pocket calculator that slowly unfolds itself once a finger presses its catch, a movement accompanied by a snatch of lush, sweeping lounge music, catchy, vapidly emotional. Dazzling in HD, reality and representation are frauds, it seems to imply, while authenticity and sentiment are easy to fake.

Such scepticism about images, bodies and our responses to them shifts to another level of morbidity when Atkins finds his way into CGI and motion-capture. The protagonist of Hisser (2015), a freckled man in T-shirt and shorts, slumps listlessly around his ikea-catalogue apartment, masturbates in a corner and sings melancholic lyrics about how “I didn’t know that life was so sad”, until his flat and all its contents, shaken by tremors provoked by a twinkly announcement-chime, begins to disappear into a hole that opens up beneath it. Occasionally, this scene of contemporary anhedonia is punctured by the chirpy intro of Elton John’s Don’t Go Breaking My Heart (1975).

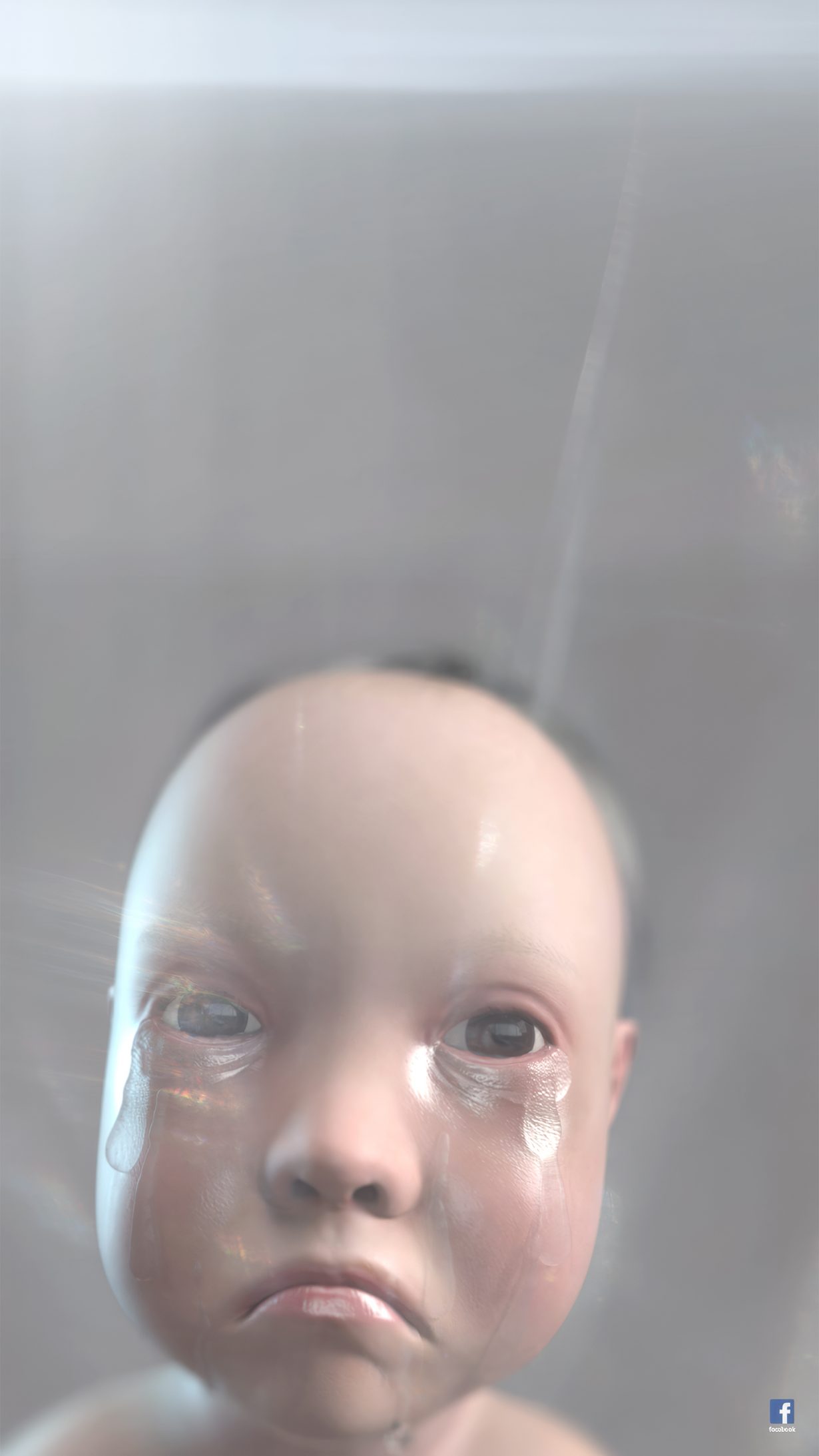

From here on Atkins’s CGI nightmare world grates the toylike visual charm of animation against ever greater gambits of disgust and abjection. The videos in the installation Old Food (2019) shift from paranoid sterility to the styling of a kitschy medieval era. In one, on an empty white plain, we see hundreds of CGI humans run towards each other and gather, only for some violent invisible explosion to burst their mass apart, or else witness a cascade of humans falling into a huge hole. In another, food ingredients and more incongruous, out-of-scale things – suited men, babies, skulls, books, the flayed skin of a human face – tumble from the sky to form bouncy, ketchup-slathered sandwiches (Untitled, 2018). They’re playfully cynical and superficial takes on a philosophical outlook that, in the last decade or so has treated humans as objects, things or matter. The weird and affecting Good Man (2017) and Good Boy (2017) capture Atkins’s complicated negotiation of the conundrum of human interiority in a culture wedded to surfaces. In Good Man, a haggard man in a medieval cloak and hood, stuck in the rain, stares at us and cries floods of tears, moaning wordlessly; its companion piece is a boy wearing a lace collar and doublet, equally tear-drenched, the liquid welling up and dripping off his cheeks, his expression desolately sad and imploring. This simulation of suffering suggests that empathy is a reflex, human experience and expression always a construct. Emphasising the point, surrounding these videos are high scaffold-racks on which hang rows of costumes, apparently acquired from German opera company Deutsche Oper Berlin. Here, such body-containing objects, that once adorned the expressive bodies of opera singers, look fusty and inert.

It can be risky to make overly personalised readings of an artist’s work, but this show is bracketed by the knowledge of Atkins’s attention to his father’s death from cancer in 2009. In the first room the oldest videos are accompanied by embroidered canvases, on which are picked out in tiny lettering lines from Philip Atkins’s own cancer diary, and the show closes with a new two-hour live-action film, Nurses Come and Go, But None For Me (2024), which stars actor Toby Jones reading the text of the diary, in a living room, to a group of young people ushered in by another well-known actor, Saskia Reeves. It is a harrowing watch: Jones is impeccable in bringing out the misery and fear of a man who knows he is going to die, the bureaucracy of healthcare, the hopelessness of those who care for their closest, and the strange epiphanies of love. Freudians and others have long argued that melancholia – or depression – can be the result of grieving that is stuck, remaining unresolved. Other analysts conjecture that depression can make us see ourselves as objects. There are disturbing drawings by Atkins of his head as the body of a giant spider, and a large ink painting of his own foot, in brownish-grey tones, as if it were made of clay. Somewhere through this chronological account of Atkins’s work a personal story intersects with modish thinking about bodies, technology, contemporary life, capitalism, corporeality and affect. Atkins peppers the show with reproductions of anonymous reviews of his work from the online Contemporary Art Daily, which vibrate with the vocabulary of post-humanist, sub-Nick Landian accelerationism – ‘The libertine desire which was co-opted by empire who rerouted its libidinal energy as fast-food addiction,’ and so on.

What gives Atkins a way out, though, from dissociation to something a little more centred is his return to his family. His father, in filmic epitaph; the gentle conversation of The Worm (2021), in which a CGI, motion-captured Atkins speaks through a crop-haired check-suited young man, seated on a stage as if a talk-show host, conversing in what sounds like a real phone-conversation with Atkins’s mum. And lastly, a room of framed Post-it notes, which Atkins made for his daughter during lockdown, to put in her lunchbox. Silly and tender, they’re made to stimulate and encourage life, at a moment at which we were all turned into objects to be administered, whether we liked it or not. Maybe lockdown broke a spell. Maybe we’re all still meat-sacks, but this time with feeling.

Ed Atkins at Tate Britain, London, through 25 August

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.