Mudam Luxembourg hosts Europe’s first major retrospective of the subversive American performance artist

“There’s a way to solve every problem,” says Eleanor Antin earnestly, dressed in a white tutu, in her 1975 video The Little Match Girl Ballet. It’s both the promise and the pretence of so much of her work. The dancer, one of the American artist’s invented personae, dreams of becoming a Russian ballerina. Art makes it possible: across several bodies of work during the 1970s and 80s, Antin conjured the life of Eleanora Antinova, the counterfactual history of a Black ballerina who once performed with the Ballets Russes. In a portfolio of prints here, she even wrote the dancer’s memoir, opening up the past as if it were a machine to be reengineered.

Now ninety, Antin has always been a political artist, pursuing a vision of a more equitable society. But her commitment to problem-solving seems deliberately wayward. At Mudam – her first major retrospective in 25 years and first ever in Europe, spanning 1965 to 2017 – the ballerina pieces are shown with self-conscious drama: the facade of a theatre from Antin’s 1986 installation Loves of a Ballerina leads to a darkened basement gallery, punctuated with dozens of photographs, videos and films, all versions of the artist as Antinova. It has the extravagance of a fantasy, the fragility of an illusion.

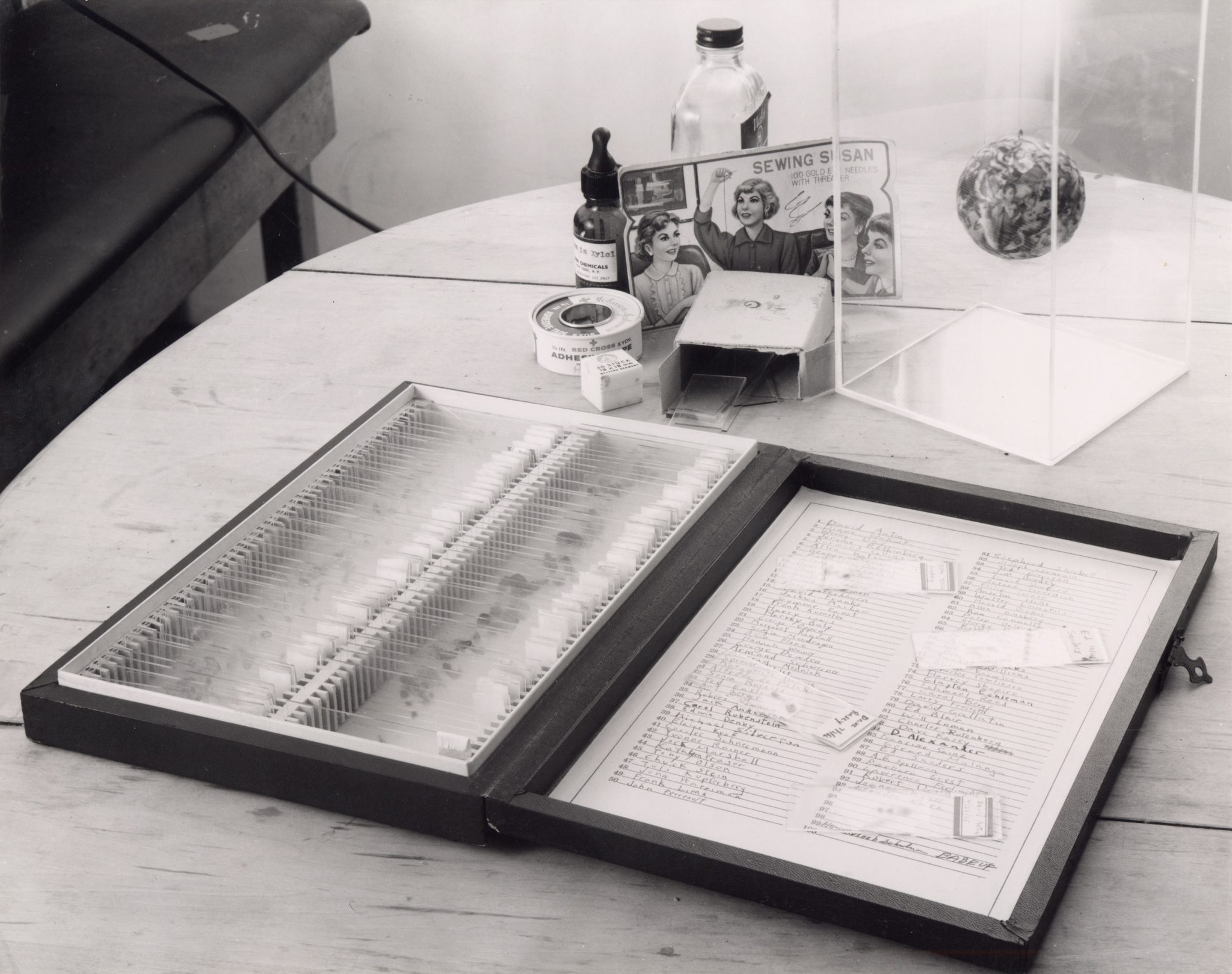

Before settling in San Diego in 1968, Antin emerged amid the Conceptualism of mid-60s New York, but had a slant relationship to the systems-oriented approach of some of her male peers. One of the earliest pieces here is Blood of a Poet Box (1965–68): 100 samples of blood collected from artists she admired, including, among others, Yvonne Rainer and Allen Ginsberg. Methodical and rigorous, it also won’t let go of romance, a project without clear purpose other than Antin’s personal impulses. Domestic Peace (1971–72) categorises conversations with her mother in annotated graphs, from ‘bored’ and ‘calm’ to ‘hysterical’. These works have faith in art’s power to find answers, to make visible the body, women and everyday lives. But the solutions are usually funny, unsure of their seriousness. In an iteration of one of Antin’s best-known works, 100 Boots (1971–73), 50 pairs of black rubber boots process down a staircase: going somewhere, going nowhere. For the original mail-art project, Antin sent postcards documenting the boots’ journey across the United States.

In a section entitled ‘Melodrama’, the waggishness verges, deliberately, on poor taste. Antin’s video The Nurse and the Hijackers (1977) stages a scenario in which ecological terrorists hijack a plane to hold oil-producing nations to ransom. Lifesize paper-cutout passengers and hijackers are moved around a cardboard set (also displayed), as if Antin hopes artistic experiment might illuminate a route out of the dead ends of history. Reassemble the pieces and another, better version could emerge. Or, the puppet-theatre setup implies, that kind of optimism is just child’s play.

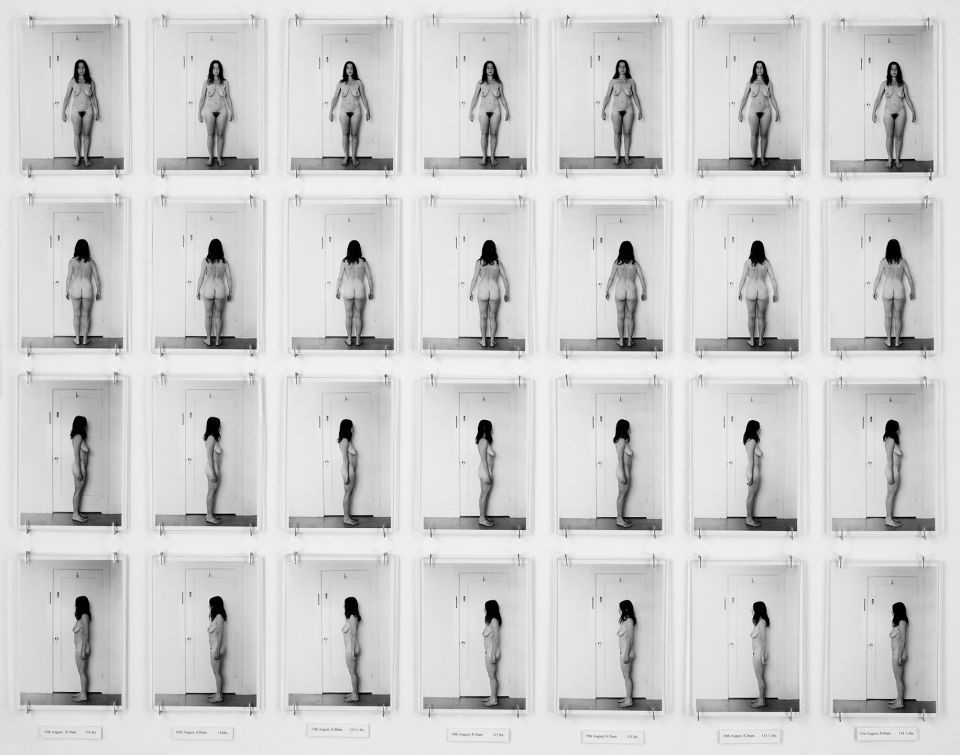

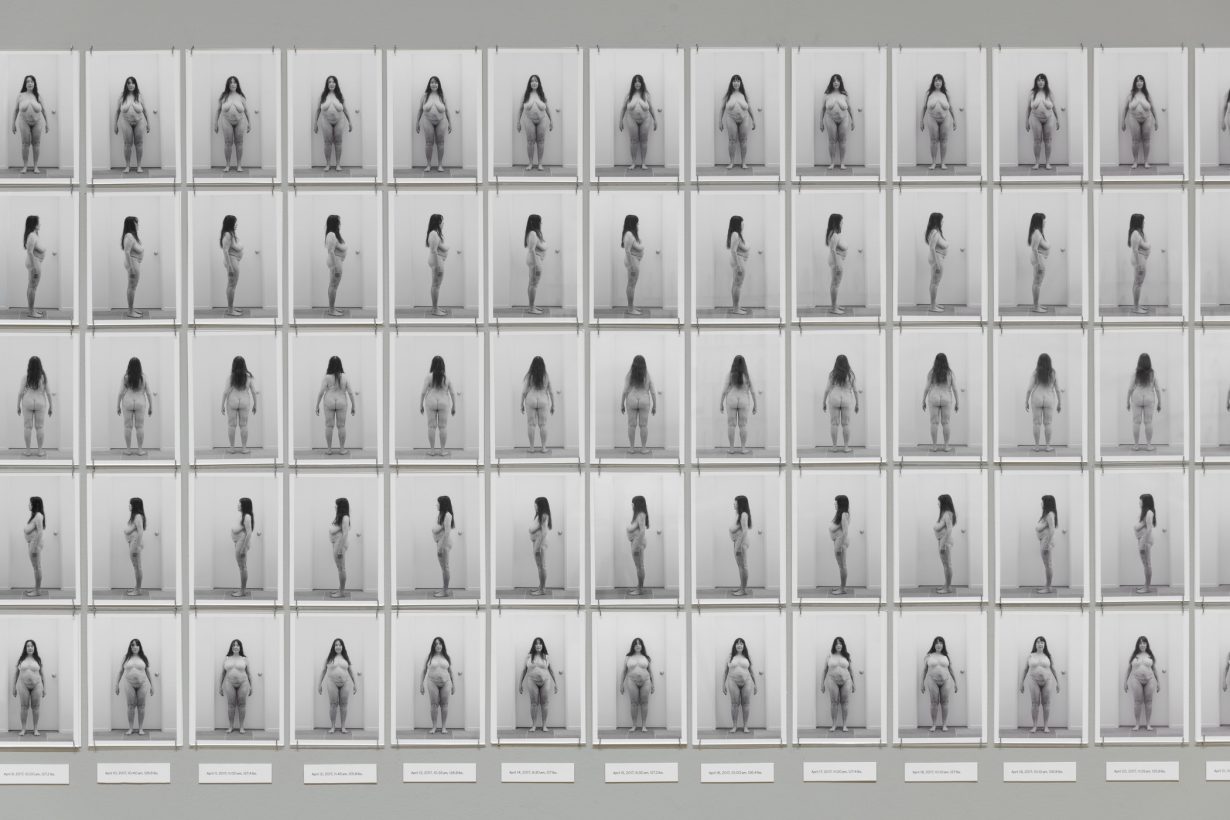

From one angle, Antin’s position can look like a cop-out. Her work imagines political interventions, but a dose of cynicism protects it from the failure of critique. It resists, knowing the system will absorb resistance. But this mix of stuckness and hope is a particularly feminist feeling. Antin’s key feminist works are here, including Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), in which she documented her attempt to lose ten pounds: across 148 monochrome photographs her naked form is gradually chiselled away like a classical nude, transformation also a sorry capitulation to a white patriarchal ideal. In her most recent work, Carving: 45 Years Later (2017), Antin repeated the diet and again documented her weight loss in a series of frank photographs. Grieving after the death of her husband, poet and artist David Antin, her self-scrutiny as an older woman is now full of subversive promise.

Eleanor Antin: A Retrospective at Mudam, Luxembourg, through 8 February

From the November 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next An Ode To Béla Tarr, 1955–2026