The self-taught, octogenarian artist’s rise was meteoric, and so a narrative formed that was by turns mythological and frankly racist. It’s time to correct the record

Most people I know would utter her name as if she were a global superstar. A singular name, like Madonna, that could, nevertheless, signify only one person: Emily. She would sign works in permanent black marker: Emlly. Not Emily, but Emlly – a phonetic spelling, the way she’d have pronounced it, with two syllables (Em-lee). But this ‘Christian’ name of hers – a convention imposed by a rapacious artworld unused to the nasal, rhotic and retroflex sounds of Aboriginal given and ‘skin’ names – actually concealed her true identity, as an Aboriginal artist whose work came out of and reflected her community.

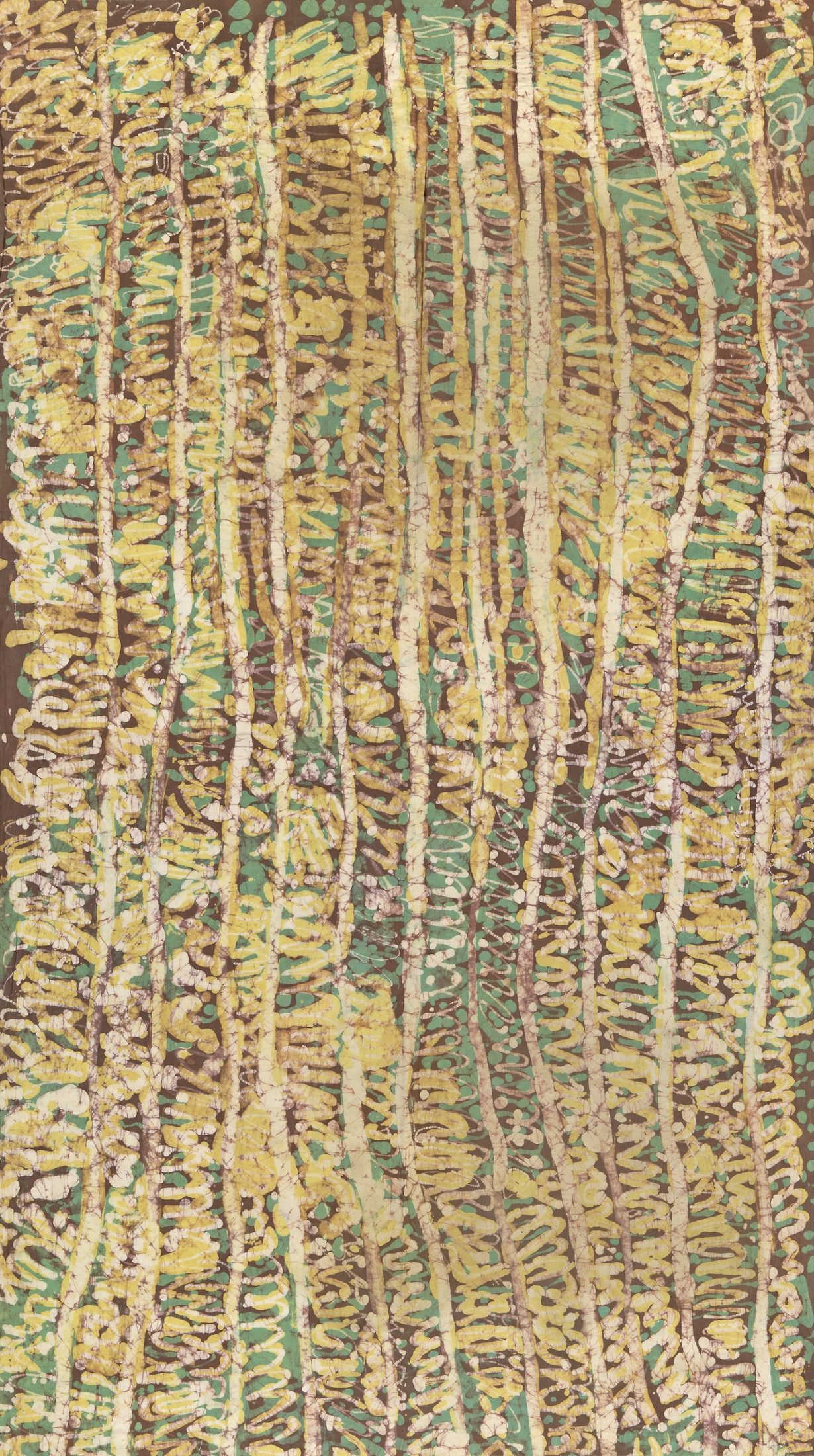

Described as one of Australia’s preeminent artists, whose bold, gestural paintings fetch the highest prices offered for the work of an Aboriginal artist, Emily Kam Kngwarray has almost mythic status in Australia. A senior Anmatyerr woman from Alhalker Country, where she was born circa 1910, west of Utopia – a group of remote clan outstations in the Sandover region northeast of Alice Springs (or Mparntwe) – Emily Kam Kngwarray began painting in her seventies. At the time it was a rare thing for a female Aboriginal artist to be lauded in her lifetime – in fact, it was unheard of. No First Nations woman had been taken as seriously by the critics and the art market as was Kngwarray, who worked outside the gallery system for most of her life. Instead, she produced works on paper, batiks on silk (a traditional Balinese form introduced to her community during the 1970s) and acrylics on canvas for the government-funded art centre at Utopia – one of many established across the farflung Central and Western Desert regions of Australia’s vast inland as a social enterprise and a means of income support in the country’s poorest, most disadvantaged and underserviced communities.

‘Emily’ was the least significant of her names in terms of identifying who she was and where she fit in the kinship system into which she was born. Kngwarray was the name of her subsection in the kinship system. In the bush, it’s known as a skin name – an Aboriginal English term where ‘skin’ conveys an embodied sense of identity and a spectrum or range of possible classifications. The skin name Kngwarray would accord not only a social identity, but oriented how Kam moved in the world, socially and culturally, imposing upon her certain marriage rules, prohibitions or avoidance behaviours (sometimes precluding direct speech to a close relative of the other gender). Her skin name also attached to her a bundle of heritable cultural rights to access, perform and represent certain stories. The artist exercised this cultural authority by painting certain ‘views’ of her Country and not others, in the same way that she could represent certain ‘dreaming’ stories – primarily, in Emily’s case, those of the yam and the emu – and not others. The term ‘dreaming’ is deliberately active, and refers to the complex tissue of interconnected creation stories that play out in the present, as much as in deep time – stories that carry with them certain caretaking responsibilities to Country and which might be said to overlay existence like a fourth dimension.

Properly, she was Kam – the name given to her at birth by her grandfather. It’s the Anmatyerr word for the seeds and seedpod of the pencil yam – a creeping vine with tangled, edible roots (also known as bush carrot) that grows above and below ground. It’s all over her artwork, less a motif and more a personal origin story – a signature almost. Indeed, by way of explication, she once declared to an interviewer, ‘I am Kam/kam’ – that is, the vine itself.

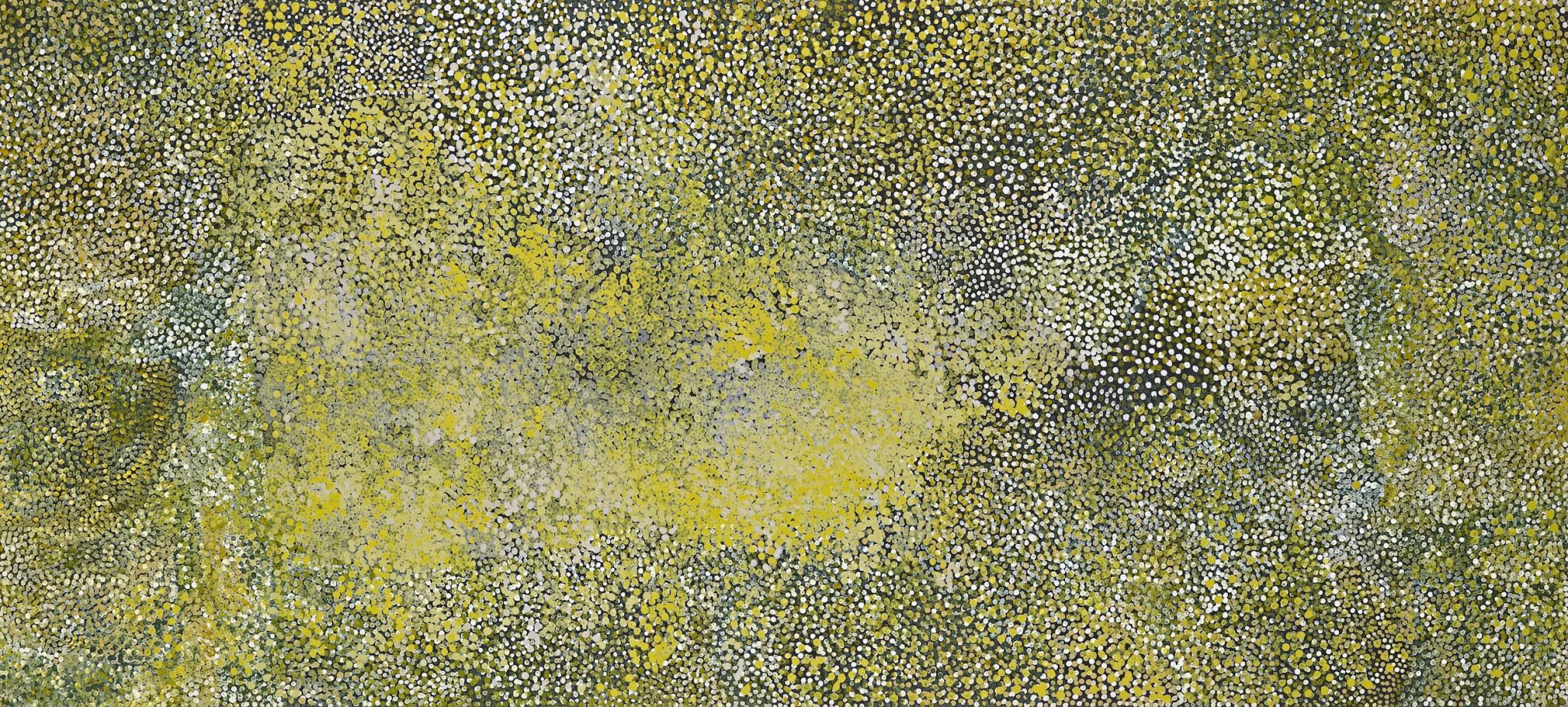

When she started painting in acrylic on canvas in 1988–89, Kngwarray’s distinctive style was noticed immediately. She already had a range of highly developed techniques – stippling, dotting, mazelike linework – for expressing the complex fourth dimension, her spiritual life and the power she drew from her Alhalker Country. Kngwarrray also had at her disposal a muscular visual language – particularly the motifs she painted, the awely, the catalogue of traditional designs that are painted in ochres on the body during ceremony. Designs she knew intimately, because they had been painted onto her body by senior women throughout her life, and which, as a senior woman, she painted onto her kinswomen. Her talent as a colourist, keen eye for composition and visual language can be seen in the multipanel The Alhalker suite (1993) – owned by the National Gallery of Australia (and featured in the most exhaustive survey of her work seen in Europe, which opens at London’s Tate Modern in July) – and in any number of works she titled Awely. Her work seemed to grow ever more assured, featuring broad, gestural arcs that drew comparisons with the Abstract Expressionists or bold, roughly horizontal lines that seem almost self consciously minimalist. Her idiosyncratic, singular vision and prolific output would lead to group exhibitions in Sydney and Melbourne, and eventually solo shows. The National Gallery of Australia purchased one of her batiks, and soon other state-gallery directors, collectors and the media would come knocking. By 1997, a few months after her death, Kngwarray’s iconic ‘stripe’ works would be included in Fluent, Australia’s representative exhibition at the Venice Biennale, during which Emily’s work was featured alongside Judy Watson’s unstretched canvases of blood tides and the tubular woven eel traps of Yvonne Koolmatrie.

By anyone’s standards, Kngwarray’s ‘rise’ was meteoric, and so to explain it, a plausible story emerged. The narrative went something like this: an elderly Aboriginal woman from a remote community paints Modernist masterpieces while sitting in the dirt, and goes on to become a one-woman industry, producing 3,000 paintings in eight years, flooding the market with work of variable quality to fulfil her cultural obligations (to share whatever she had with her extended family). The myth was driven in part by the overheated demand for her work, unleashing a small army of unscrupulous dealers, not to mention fraudsters, a few sycophants and – as her work fetched ever higher prices – presumably a lot of humbug. But in the telling of her story, the writing has often lapsed into mystification or incredulity, sometimes reanimating frankly racist tropes in the process. People couldn’t get their heads around the enigma. When filmmaker Warwick Thornton imagined a love story in his homeland in central Australia in Samson and Delilah (2009), he inserted the trope of an overworked senior woman artist as the beloved grandmother of the film’s titular female lead character; her death is a catalyst for much of the horror that follows in the film. In these media representations, ‘Emily’ has been characterised as an outlier whose extraordinary skill disconnected her from her community, leaving her with the romanticised trope of being ‘torn between two worlds’. In all these versions of her story, the artist is denied one thing: her voice.

The eponymous exhibition Emily Kam Kngwarray in London this summer might feature the name of an individual artist – a trope beloved of the West – but the exhibition, which was first curated by Hetti Perkins and Kelli Cole for the National Gallery of Australia in 2023, revisions Emily’s work and wrests back the narrative popularised in the media of a singular genius working alone, seemingly inspired by the gestures of modernism but otherwise untouched by modernity. It recasts Kngwarray not only as a much-loved member of her community but a practitioner – and innovator – of its highly distinctive artmaking traditions, which is also expressed in the virtuosic work of her nieces, Kathleen and Gloria Petyarre. Kngwarray’s kin have had strong input into this show, endorsing a new rendering of the artist’s Anmatyerr bush and skin names, in what is more or less phonetic English (our languages are spoken, not written). But when she started painting, the critics didn’t have the language to describe her work or read the iconography within it – they had no road map, let alone a pronunciation key for her bush and skin names. For a considerable time, her art – rightly or wrongly – would be ‘decoded’ by white anthropologists.

“We’re trying to turn the narrative around, to strip back a lot of that international-acclaim-mythologising of the artist and to really ground her work back in Country,” Perkins told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Kngwarray was a traditionalist when it came to representing her beloved country, Alhalker, and the stories that animate it – stories that she returned to again and again: the deeply personal big yam dreaming, for instance, or that of the emu that harvests the plant, or the ceremonial body designs, or awely, which she transferred to fabric and later to canvas. The strongest impression I was left with after visiting the 2023 exhibition at the NGA was of a highly motivated, energetic artist with a clear sense of purpose and almost superhuman physicality, a sublime, if risk-taking, colourist, and an extraordinarily confident maker who knew precisely what she was doing. There is nothing abstract about her vast canvases or works on paper, which she only began to make when she gave up on batik’s labour-intensive, wax-resist dyeing method as her eyesight began to fail.

As an exhibition, Emily Kam Kngwarray at the NGA unfolded in a way that I’ve never quite seen before. Eighty-nine works drawn from public and private collections all over the world, which survey a big life, and a much deeper story – the supernatural odysseys of totemic animals and life-giving plants across time to the present. Everything is spiritualised, even colour. Displayed in chronological order, you could follow the artist’s trajectory from those unfurling works on textiles, mazelike scrolls hung from the ceiling, to compact works on paper and monumental canvases of a size that would make most true painters shrink. From the first painting, you could track the tentative first steps of Kngwarray’s practice as it arched into self-confidence with the overblown even lairy midcareer paintings that are laden with colour. At some point, it all gets distilled to its essence: it is in Kngwarray’s worldview, painted in monochromatic works, such as in Untitled (awely) (1994) – horizontal black lines on a starkly white background – that I see a lasting testament to the cultural knowledge and forces that shaped her. Although by no means her final works, they do act as dramatic signposts in the dramaturgy of the exhibition, as though immovable set pieces that seem to resonate with the totality of everything that came before, harmonising the efflorescence of her practice – if not its sheer volume – in an economy of line and absence of colour.

Her kinswomen, most of them practising artists themselves, are not immune to the strange power of her work a quarter of a century after her death. Two of them, Jedda Purvis Kngwarray and Josie Petyarr Kngwarray, are quoted in a text that lines the walls of the exhibition. ‘If you close your eyes and imagine the paintings in your mind’s eye, you will see them transform. They are real – what Kngwarray painted is alive and true. The paintings are dynamic and keep changing… The Country transforms itself, and those paintings do as well. That’s why the old woman is famous.’

Emily Kam Kngwarray is on show at Tate Modern, London, 10 July – 11 January. Work by Emily Kam Kngwarray, My Country, is also on show at Pace London, 6 June – 8 August

Daniel Browning is a Bundjalung/Kullilli artist, writer and radio broadcaster

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.