From the largest retrospective of Warhol in China to date, to the art of Belgian comic master Hergé, your autumn guide to shows

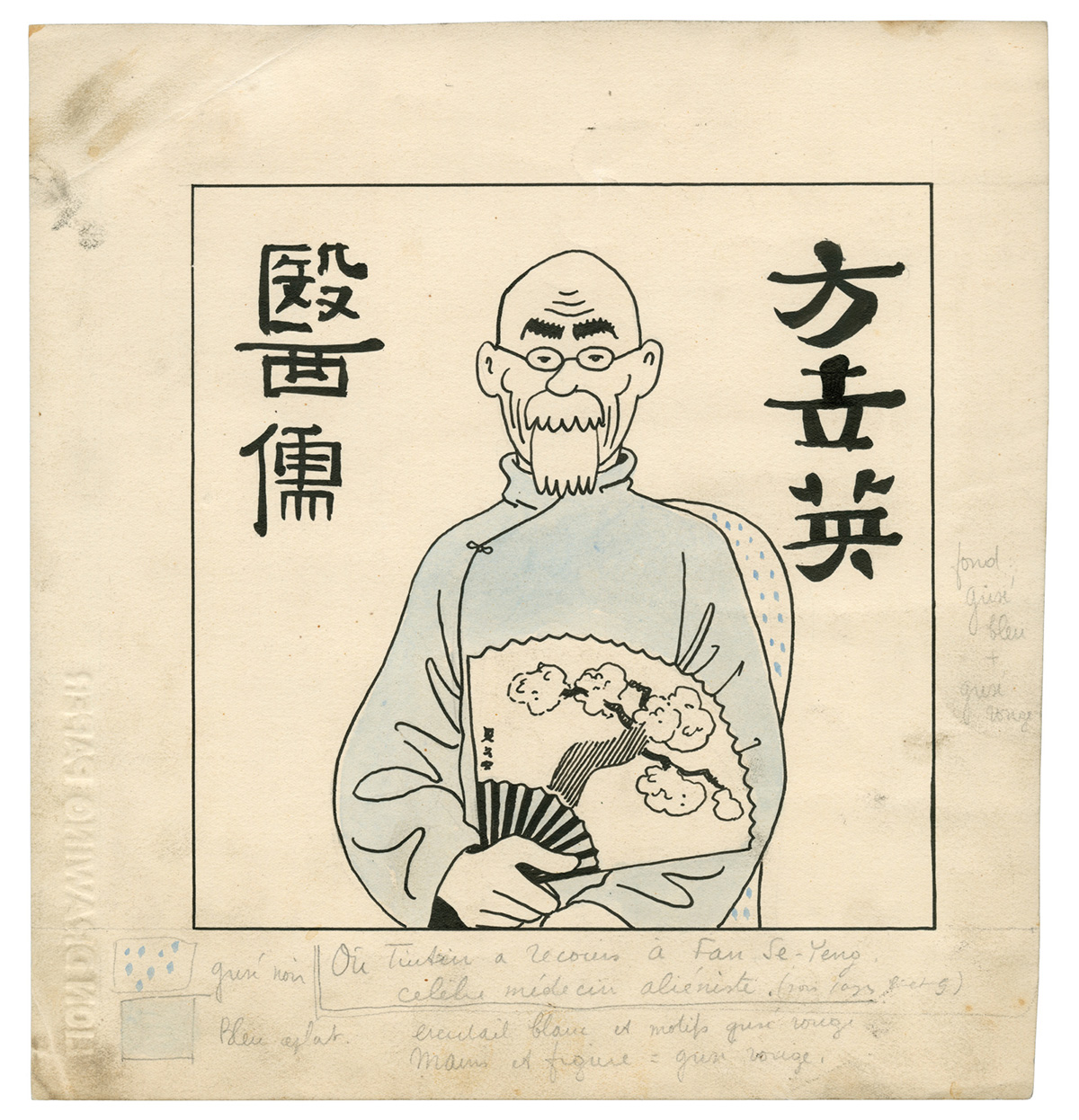

A heady mix of nostalgia and invention is on show at Shanghai’s Power Station of Art, where Tintin and Hergé (until 31 October) showcases the art of the Belgian comic master (real name Georges Remi) and the development of his iconic character. Naturally the attention is focused on The Blue Lotus, generally thought of as Hergé’s first masterpiece and originally serialised in the weekly Belgian newspaper supplement Le Petit Vingtième between 1934 and 1935, and set in China during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, in 1931. While the Japanese are portrayed as buck-toothed brutes, Tintin’s guide, Chang, is based on Hergé’s friend the Chinese sculptor Zhang Chongren (then studying in Brussels), who gave the comic artist advice on creating the China of The Blue Lotus as well as lessons in Taoism and Chinese art and calligraphy. Chiang Kai-shek was so impressed by that depiction (and its positive influence on European perceptions of China) that he later invited Hergé to visit the place he’d imagined for real. Although given that, by that time (the late 1930s), Japan had bombed the country to smithereens and Europe was plunging into its own conflict, it’s understandable that he didn’t take the Nationalist leader up on the offer. Still, he’s here in spirit now, with an exhibition that examines his artistic influences (Hergé collected Jean Dubuffet, André Raynaud, Lucio Fontana and Andy Warhol, among others), as well as showcasing his drawings and photographs and other ephemera. Don’t expect a similar show to take place in the Democratic Republic of Congo, however, a country that the Belgian depicted in a 1931 collection as populated by a people who were backwards and lazy and in dire need of European civilising.

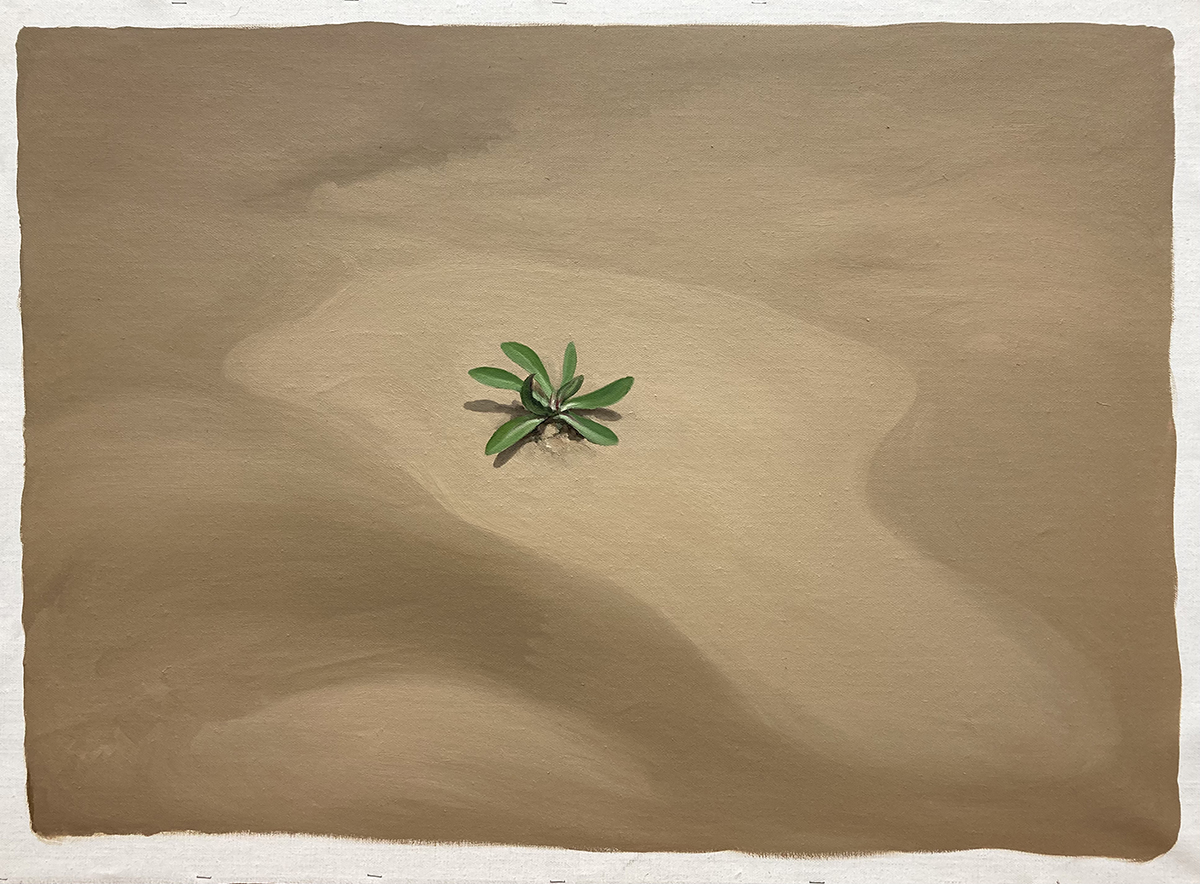

Chinese painter Yan Bing first came to prominence during the late 2000s through works that mixed the raw materials of his homeland (among them earth, grains, pulses and animal hides), found objects (farm tools, for example), installations and figurative oil paintings in a manner that former UCCA director Jérôme Sans once compared to Italy’s Arte Povera. Yan Bing described it as a form or resistance to a world that was increasingly digitalised, abstracted and conceptualised, while at the same time being dominated by a philosophy of anthropocentrism. Or a return to simple truths and the notion of humans as comprising just one part of a living world. Such thinking has only grown in prominence in the decade since, so his latest exhibition, Suddenly Everything Became Clear, will be one to watch at Shanghart’s Shanghai HQ (until 17 October).

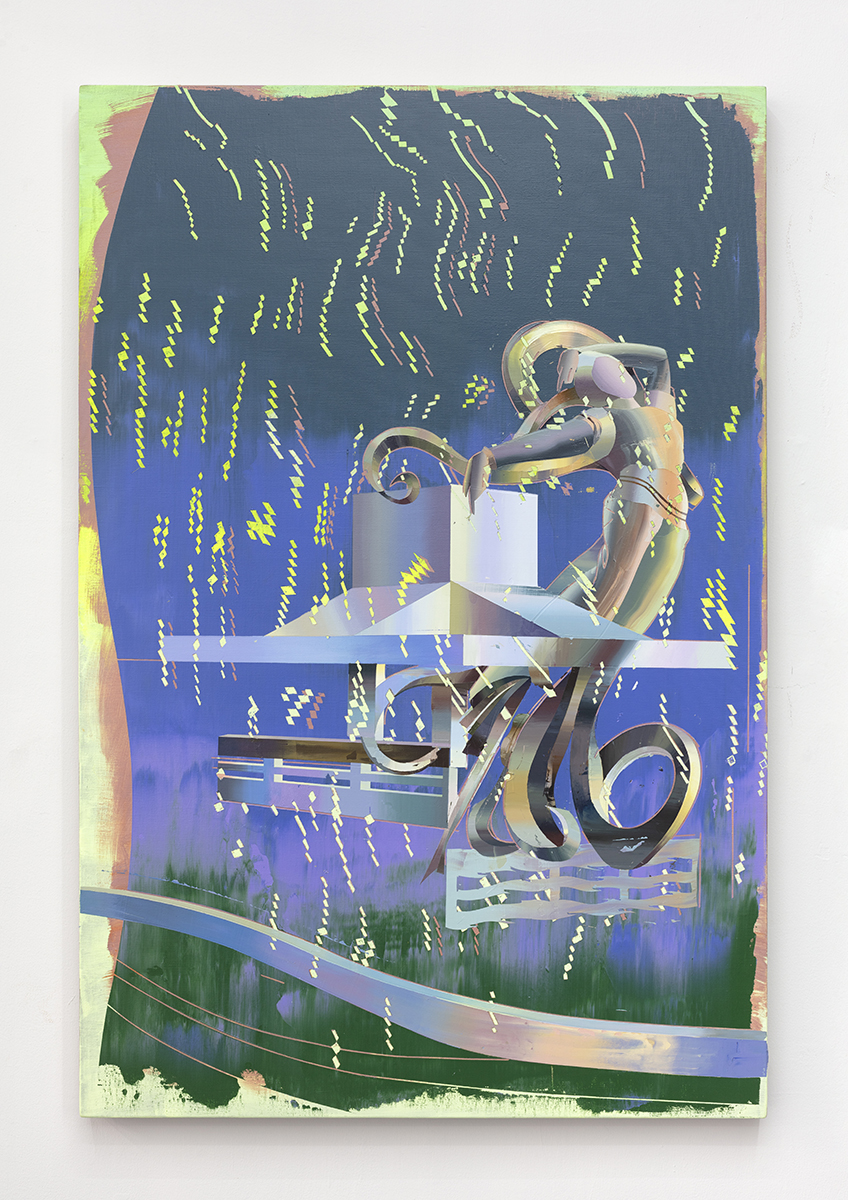

Those of you who want to experience the flipside of that, however, will want to head to Shanghai’s Chronus Art Center, where AI Delivered: The Abject (until 17 October) corrals the work of nine artists and collectives alongside the theoretical legacies of computer scientist Alan Turing, philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett, and art-theorist Hal Foster to explore the epistemological limits of artificial intelligence and to explore a world that’s saturated by it. Works by Sofian Audry and Istvan Kantor (aka Monty Cantsin), H E Zike, Lauren Lee McCarthy, Casey Reas and Jan St Werner, Devin Ronneberg and Kite, and Tonoptik investigate neural networks, machine learning, the nature of subjectivity and the relationship between humans and nonhumans. Or pretty much – again – the reduced world of lockdowns. A second chapter of AI Delivered launches in November.

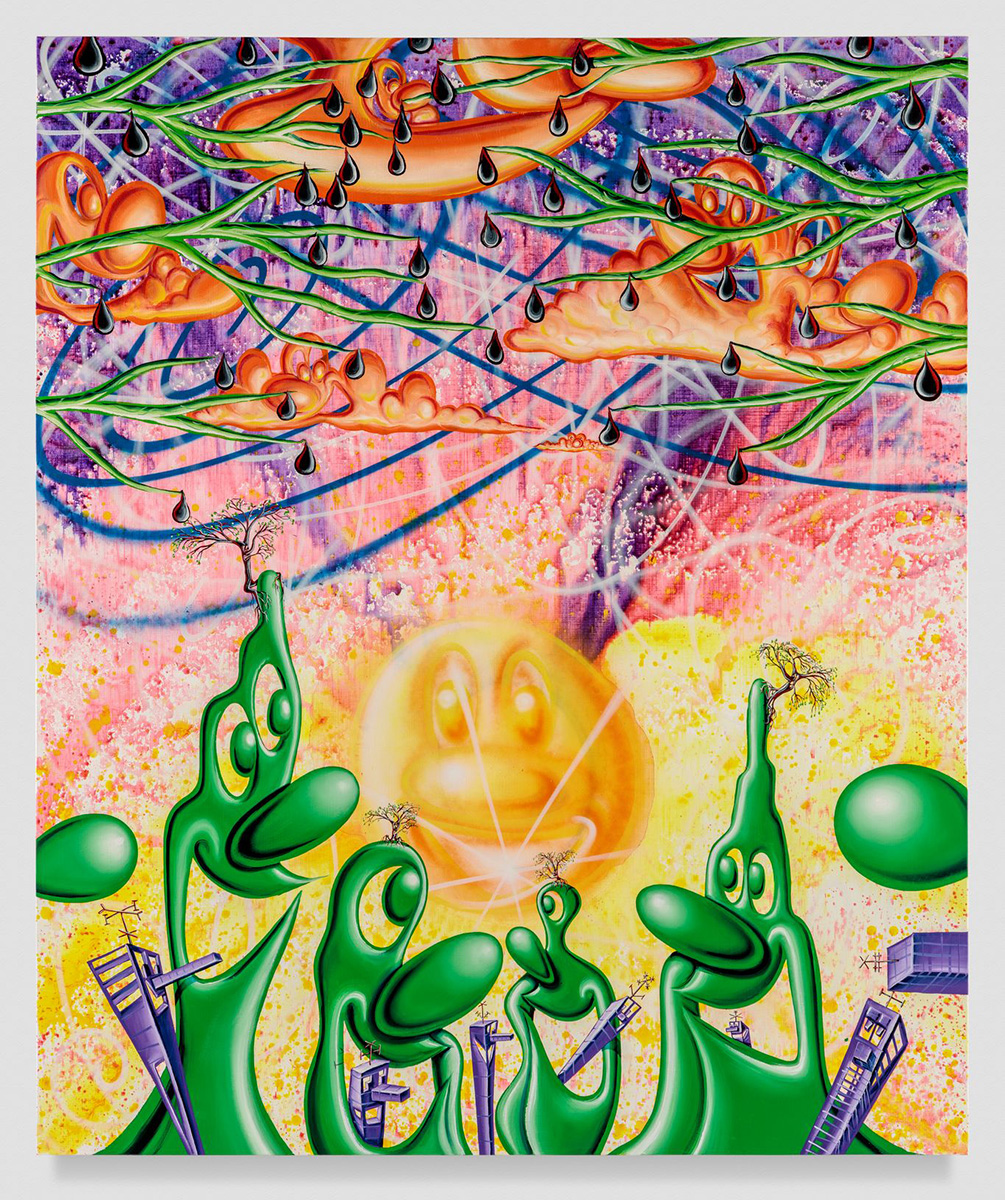

American artist Kenny Scharf emerged as part of New York’s East Village art scene alongside Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. And unlike them he’s still alive, and best-known these days for paintings that straddle pop culture, street art and visions of a tripped-out future. The better-dressed among you may have caught his Autumn 2021 capsule collection for Dior, decked out with cartoon playing cards and tessellated patterns – think blue and white china meets Islamic geometry with grinning caricature kings thrown into the mix. For the rest, the artist brings his latest 2D works to Shanghai with his first gallery show in China at Almine Rech (until 9 October). The exhibition is titled Earth and contains representations of friendly- looking anthropomorphised animals and plants, with a sort of curvy Edenic vibe. Seemingly innocent and fun-looking at first glance, the new works conceal a hidden warning featuring Chinese characters for ‘plastic’, ‘petroleum’, ‘carbon dioxide emissions’, ‘global warming’, ‘pollution’ and all the things we produce to fuck up this planet.

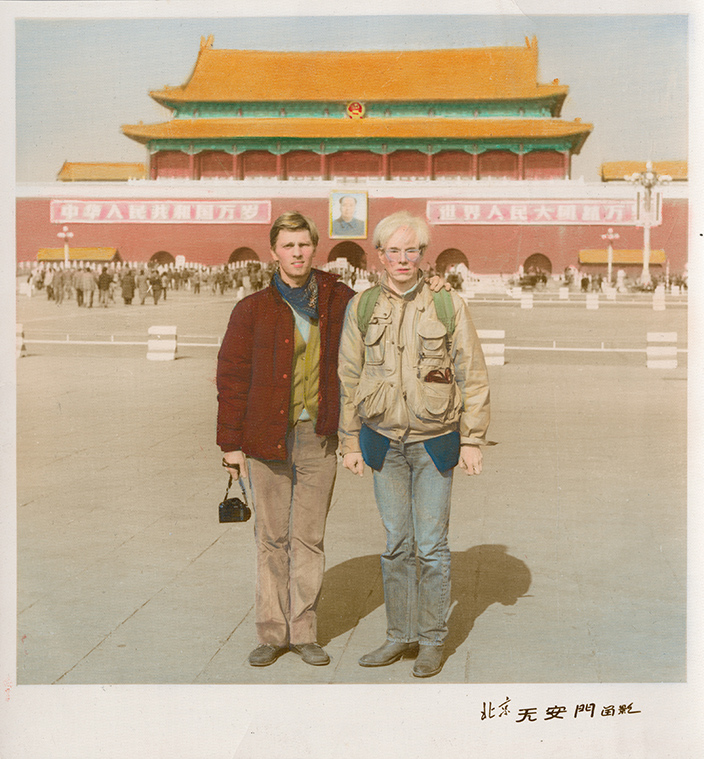

There’s no escaping abjection, it seems. But for those of you who don’t want to escape the vibes of that New York scene, UCCA Beijing is hosting the largest retrospective of Warhol’s output in China to date. Becoming Andy Warhol (until 10 October) features 400 of the Pop master’s drawings, paintings, photographs and films, with a focus on hybridity and repetition and how the great one’s life and lifestyle became fused with his art, complete with a replica of the famous red couch from his studio, The Factory, upon which you too can enthrone yourself, mimic the poses of one of his superstar subjects and get very, very busy on Instagram or WeChat. Fifteen seconds – for that’s the price of progress – for everyone.

Talking of democracy, it’s over to Hong Kong and Para Site for Liquid Ground (until 14 November), curated by Alvin Li and Junyuan Feng from the not-for-profit’s annual open call for exhibition proposals from ‘emerging curators’ – whatever that means at a time when most of us are emerging, blinking, into the light. The ‘liquid ground’ of the title refers to the land reclamation projects that are ongoing across East and Southeast Asia (and beyond), the dumping of sand and rock into the sea in order to expand coastal cities and their infrastructures. Works by Leelee Chan, Cui Jie, Future Host, Ho Rui An, Travis Jeppesen, Jessika Khazrik, Heidi Lau, Lee Kai Chung, Riar Rizaldi, The Centre for Land Affairs, Yi Xin Tong, Alice Wang, Gary Zhexi Zhang, Zheng Bo and Zheng Mahler explore issues of extractionism, capitalism, the overarching mindset that nature is a force to be worked against and a blind ignorance of the consequences of impending climate catastrophe. Picking up, then, where Kenny Scharf left off. Lurking in the background of course is Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam’s 2018 Lantau Tomorrow Vision – a proposal to reclaim 1,700 hectares of land from the sea in order to turn Lantau Island into a new economic hub.

On the subject of reclamation, American conceptual artist Sherrie Levine makes her Hong Kong debut at David Zwirner’s island outpost (until 13 October), with an exhibition that showcases her use of appropriation to challenge the accepted stereotype of the male modernist master and to challenge received notions of authorship and authenticity, and with it, the interpretation of images. On show will be examples of some of the artist’s seminal bodies of work, including After Henri Matisse (1985, featuring a series of faces, copied by Levine, in ink and graphite, from works by the Frenchman, and floating on empty paper sheets) and Monochromes After Renoir Nudes (2016, which use a process of pixelation to consolidate the range of tones in this Frenchman’s paintings into a single, all-encompassing monotone). Also on show will be Brazilian Ex Voto Figure: 1 (2019), part of a series of sculptures cast from non-Westernwooden originals that were used in a range of rituals but are now rendered both unoriginal and ‘elevated’ to the status of works of art, echoing also the way that many modernist artists treated non-Western artefacts in the ‘invention’ of their own art. As is the case with reclaimed land, nothing comes from nothing.

From the Autumn 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia