In the traditional distinction between architecture and art, all architecture is underlined by a contract in which the client/architect relationship is declared. This is what is called a brief. Even the most outlandish-looking hypothetical projects by Ettore Sottsass or Archigram carry within them an intrinsic idea of an intended good provided as a service. To have an interest in architecture and design as an artist means that occasionally you can lend yourself to be of use and, in so doing, blur the traditional role reserved for you within the art institution. As I have an interest in historical decorative objects, I was asked to design, curate and make artwork for a show that bridges both Nottingham Contemporary and Chatsworth House. Chatsworth House in Derbyshire is one of the most visited historic palaces in England and is a baroque building crammed with objects and artworks collected over 500 years by the same family, the Dukes of Devonshire. I was to select a range of objects from the house, and present them in the white interiors of Nottingham Contemporary. At Chatsworth the objects form part of a layered and complicated environment in which no individual item is seen clearly; rather, each forms part of an elaborate and dense historical matrix. Within this baroque world, objects may draw your attention because of their staging – they may be the only white object in a very dark room, for example – or on a qualitative basis, as the most elaborate or finest of a series of comparable objects, or alternately they may have a particular historical association that makes them noteworthy. None of these criteria are necessarily relevant to a contemporary art institution, whose white walls continue to push towards sculptural staging for effect and ‘intentionality’ for its rationale. And yet, if the staging of an object creates an aura of seriousness, people will take it seriously. This is the deadpan with which I have had to approach organising and selecting the objects for the show.

My half-imaginary enemies accuse me of making ‘traditional’ work

As we no longer live in a world where outraged Le Figaro critics hurl cabbages at ballet dancers, censure now happens through such means as refusing to buy, refusing to write about or refusing to show. My half-imaginary enemies accuse me of making ‘traditional’ work. By this I imagine that they see grubby old illustrations redolent of arcane discourse, or, conversely, of decorative garden-room prints for queens living in the Hamptons. Either a world of irrelevant, labyrinthine premodern pedantry, or a world of superficial Europhiles and their scatter cushions. It should go without saying that in order for something to be traditional, strictly speaking it must form part of an ongoing tradition. There has been no regular presence of historically inspired architectural drawings within the contemporary artworld, but the occasional ignoring of the context for my work says a lot about what the aesthetics of contemporaneity signifies for many of its viewers.

I am partly responsible for the suspicion my work can sometimes arouse. Flirting with the fusty, the Tory and the decorative is a form of drag that I alternately enjoy and feel queasy about, depending on how immersed I become in the role. I get approached every so often by artists or architects who consider themselves to be working within a classical tradition. They commiserate with me that, just like them, I am trying to make the past relevant, or trying to say that classicism can be soooo contemporary to people ignorant of the higher truth. They imply that classicism exists a priori within culture, lying dormant, and waiting to be revived if only the wisdom of Andrea Palladio were followed. This is borne out in the literature produced by its leading architects, many of whom emphasise the supposed natural origins of the classical orders. God, either as metaphor or actual being, is implied as the originator of the golden mean and the corresponding classical proportions that our times are so wilfully and imprudently neglecting. Lest we forget, Britain lost its empire with the advent of the modern and Rome fell to the barbarians once its meticulously upheld architectural rules began to be slackened. That the classical is a dustbin for disgruntled provincial architects should make us view it with particular interest and more so because of the comedic ways in which that strain of architects delusively view themselves as heirs to a very grand tradition.

Flirting with the fusty, the Tory and the decorative is a form of drag that I alternately enjoy and feel queasy about, depending on how immersed I become in the role

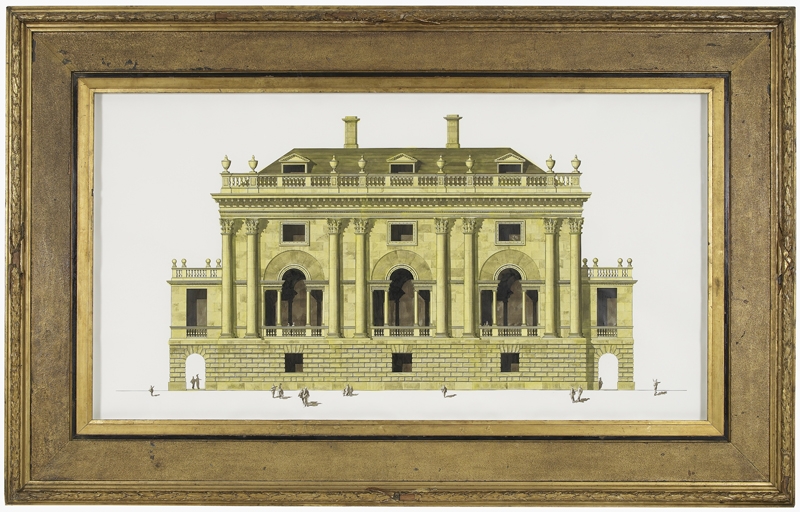

The show at Nottingham about Chatsworth is a pseudo-architectural study of newness and oldness. It begins with a set of digital models of the future house before construction in the late seventeenth century and shorn of the later eighteenth-, nineteenth- and twentiethcentury additions. These images mimic the final stage of design and present the purified house in an abstract space of limitless possibility. The objects chosen from the collections represent all the shiny luxuries that money could buy, and are displayed with some of the new-money glamour that these objects must have possessed at the time of purchase. Fresh boulle marquetry cabinets direct from the workshops in Paris, the latest silver designs by Huguenot craftsmen, huge Delft pyramids in Chinese style. These objects were primarily imported, or at the very least had to make the perilous journey from London to Derbyshire, and some were considered so important that they travelled from house to house with the owner. At Chatsworth there hangs a solid silver demountable chandelier that still has its travelling case, for example. The function of the silverware, which when arranged into tiered buffets alludes to papal princely luxury, was primarily to carry material wealth (which could be remelted and has intrinsic value), and certainly served to impress visitors. But more than this, these objects were visual markers that carried the eye in and through a route that in its spatial organisation was a choreographic embodiment of power, authority and history. The Delft flower pyramids, fabulously expensive in their own right, were to be seen in rows, on parade as a vast accumulation of wealth shown to its best advantage by the repetition of objects along a vista.

The sequence of parade rooms at Chatsworth, which form the core of the visitor experience today, was a sort of visual and experiential representation of the personal power of the Duke, and your relative position to him. The route around the house begins in the great hall, which pretty much anyone in the seventeenth century who wore a hat had access to, encompasses dining rooms, formal parlours and state bedrooms, and ends up in the piss-cupboard behind the private closet, which would have been accessed by only those closest to the owner of the house. The rooms comprising this sequence, known as an enfilade, were symbolically titled things like parlours, dining rooms, bedrooms, etc, but were in fact demarcators of your social position depending on how far you were allowed to progress through them. Chatsworth is a perfect example of a house that serves as an emblem of the social order, in which the way that the space is occupied gives one the measure of one’s social rank within the neighbourhood, the county or, in the case of royal residences, the kingdom. How this type of interior layout evolved, and the uses it put its fine objects to, are important in our understanding of the evolution of our art museums. This would be a line of development from the Elizabethan ‘long gallery’, or ‘walk’, and not from the cabinet of curiosities (which has a similarly country-house origin, but one tied up with private connoisseurship). The long gallery, designed for exercise and to impress guests, was lined with portraits and battle scenes aimed at aggrandising the wealth and position of the owner. This history is certainly more resonant with the experience of sleepwalking through the countless Warhols and Basquiats that grace the walls of museums and private foundations, artworks whose main function is to demonstrate to the visitor or rival institution the power and wealth of the patron in being able to acquire and house objects of particularly high cultural and monetary value.

The objects chosen represent all the shiny luxuries that money could buy, displayed with new-money glamour

Unlike a museum of decorative arts, which values the maker’s mark or the development of a craft through time above all else, the association of owner to object is the most important thing in a stately home. Art at Chatsworth is presented as part of an ongoing ducal collection, where the taste of the generational line is of greater interest than the individual contents of the house, Leonardo da Vinci drawings excepted. Some of the objects I selected communicate a historic link directly, such as a Peter Lely sketch of the first Duke in court dress, or the large silver pilgrim bottles engraved with the ducal crest. There has been a recent attempt at Chatsworth to crystallise this rationale through the creation of a display by Jacob van der Beugel in which the signature motifs of the dna code of the present Duke and his heir have been turned into moulded porcelain reliefs that line the walls of the ceramic gallery between the vitrines.

The days of ‘brown’ furniture connoisseurship are long gone, but although visitors no longer carry pocketbooks detailing how to distinguish between Georgian antiques, interest in how people once lived in these large houses has grown. The National Trust lays out silver-framed photos and chamber pots of family members that no longer own the houses. Each house with the Trust has a list of the priority objects to be saved in case of fire. When such a calamity recently engulfed Clandon Park, among the prize objects rescued were knickknacks that told of family history and connection to the place. Rare eighteenth-century furniture competed for priority over wedding photos of long-dead people with a scant place in public history. At Chatsworth, this provenance is taken to great heights in part because it is unbroken, as the family still owns the house and continues to live in a part of it. This provenance plays out mightily at auction. The Chatsworth attic sale five years ago brought in crazy prices for soap-dishes and magazine racks. Also of increased interest at the moment is the display of life at these houses that mirrors the present-day visitor’s own historic connections to such environments. The below-stairs experience has therefore been duly sanitised for the baby boomer descendants of the nineteenth-century scullery maid. Here in lovingly restored kitchens, among gleaming copper and scrubbed pine, retired volunteers show smiling little girls how to make nineteenth-century cupcakes using the original moulds. The volunteers are not expected to take the reenactment a stage closer to the historical truth by taking a morning shit in a communal bucket under the table.

There is an element of revenge on the part of middle-class hordes eating and buying their way through historic houses. Although some who still own their family seats make a good deal of money out of the lavender pomanders and Edwardian nostalgia books on sale, there is no doubt that the visitor is now the client, which the house is expected to adapt to and entertain accordingly. The food court at Chatsworth is vast, the gift shop has an unrivalled knowledge of its customer base and the events and activities range from pianist and tv-presenter Jools Holland’s evening concerts on the lawn to lace-making classes for weird teenagers. The country house’s decline and its rescue by tourism has of course an ironic echo in the original eighteenth-century grand tourists visiting the remains of ruined and collapsed empires to bring back inspiration for their country homes, as well as the odd souvenir.

Some of these souvenirs are shown in the final room at Nottingham, such as a huge Roman marble foot fragment, as well as some of the objects these remains directly inspired, like a solid marble bath in the antique Roman style, by a follower of Antonio Canova. There is even a set of antique Roman hand fragments purchased by one of the Dukes directly from Canova’s studio. My drawn panorama of imaginary Roman funerary monuments acts as a backdrop to these. They are a made-up archaeological cross-section of the Via Appia, the suburban road between Rome and Apulia, in which the great and good in the ancient world were buried. Some areas of the drawing show dramatic national complexes, some show how competitive funerary real estate had become on this prize stretch of landscape. These tombs are represented as being in the ninth century ad, when the Western Roman Empire, repeatedly sacked, had finally collapsed. As a result, some of the architecture still retains basic definition and has some colour and detail, while in other areas nothing remains but rubble poking out of the soil. This Ozymandian room terminates in a pair of magnificently gaudy but completely dilapidated coronation thrones, used by George IV, and William IV and Queen Adelaide. These are the best examples Chatsworth has of objects designed to be visible from a distance, and aim to embody power and importance. They are very bizarre things when seen outside a cathedral. Just as contemporary art in a historic setting is framed as a ‘surprise’ or an intervention, historic decorative objects in contemporary settings are framed as weird, eccentric sculpture. If the question of conservatism is one of context, then it is therefore also one of institutions. The self-defined object groupings and audience expectation characteristic of each venue are of course attempts to protect the art we know and expect, which can appear a good deal more fragile when exposed to an alien audience. However, if I may appropriate a metaphor from the grand tour, Rome had no need of protective walls while it still had its empire.

This article first appeared in the September 2015 issue of ArtReview