The artist explores the worlds of freelance and precarious labour, and the effects that they have on workers’ ideas of self and wellbeing

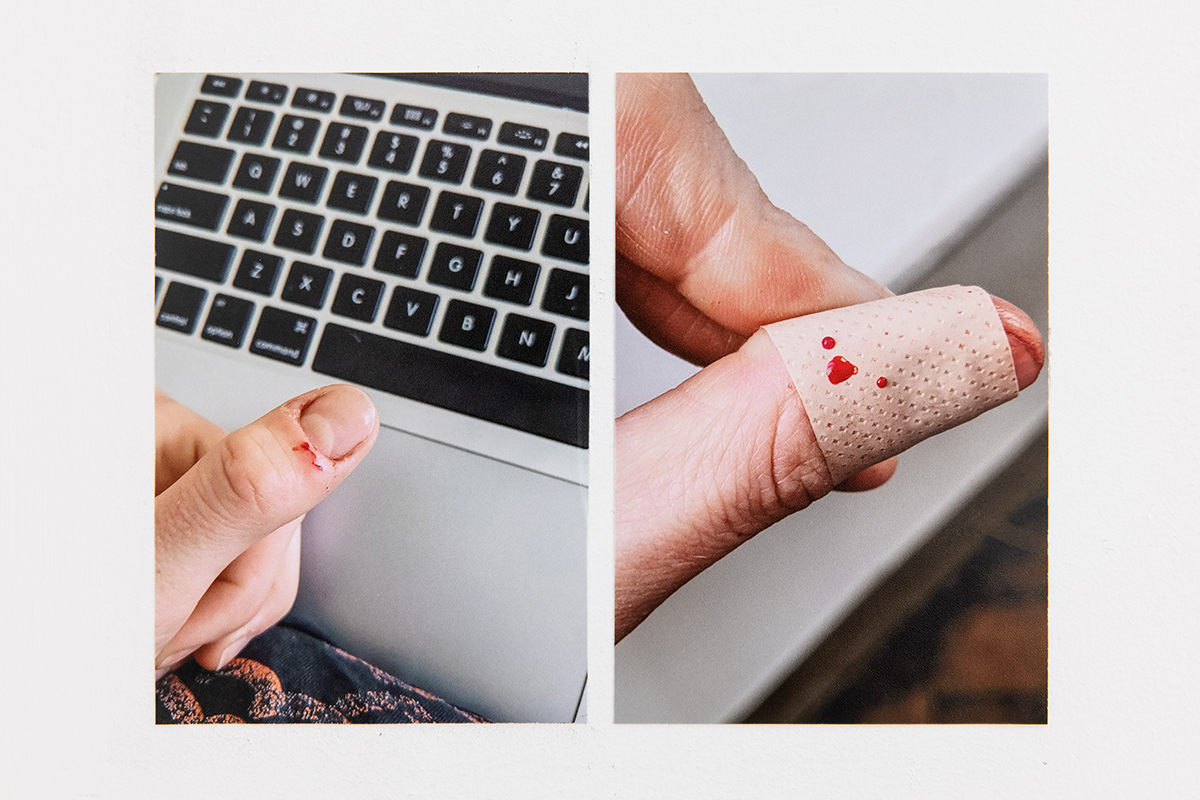

There are bloody thumbprints dotting the desk, with dark drips on a Post-it note and crimson smudges on the photocopied images of architectural caryatids that cover the desk’s surface. A woman clutches at her thumb, alternately covering it with her fingers to quell the bleeding, then nervously biting and picking at it to make it worse. “Of course I want to make you happy,” she placates an irate client over the phone, “I know you have other deadlines.” The bleeding isn’t stopping. “Look,” she emphasises, “I really want this. Absolutely. Yes, yes, yes, I can do that. I want to give you what you want. ok, tomorrow, I’ll get it to you tomorrow.” She ends the call, hangs her head and curses.

This is Helen: she’s a freelance advertising producer of some sort, who likes pastel blazers and button-up silk shirts, and lives in a light and airy first floor apartment in Berlin. And she likes cooking, in the pitifully small convection oven that sits on a counter in her grimy kitchen; she once cooked a whole chicken in it, lasagne, birthday cakes and… cookies. She made cookies, would you like a cookie? This is the incessant refrain throughout Rosa Aiello’s taut and nerve-racking 47-minute video Caryatid Encounters (2021), as Helen repeatedly practises and delivers her spiel for a series of prospective flatmates: “The wallpaper is all original, and we get lovely light in here in the mornings”; “I absolutely love the views here, you should see it at sunset, it’s just magic”; and on.

At the load-bearing centre of the narrative is Helen’s current work commission, a video advertisement for Sanssouci Palace, an eighteenth-century royal retreat on the outskirts of Berlin. Standing outside under a set of ornate figurative columns – women with arms upheld to appear as if holding up the building, the titular caryatids – a representative from the palace sets the simple assignment: “We want you to inspire people to come here. Make them fantasise about us. Get them to imagine their most important life events taking place here. Weddings, conferences, announcements, funerals. You can make them want that, right?” Helen eagerly agrees.

Helen is a model freelancer: relentlessly upbeat, adaptable, available. And tens of thousands of euros in debt. Freelancing is a careful and well-rehearsed precarity, where you can’t look what you are (broke and desperate for work) because then you won’t get the work you need. And typical of freelance life is Helen’s blurring of personal and professional boundaries, where lovers, family, friends and flatmates all need the same well-honed, high-energy pitch as a prospective client. While styled like a quirky HBO drama – imagine some sort of cross between Six Feet Under (2001–05) and Dawson’s Creek (1998– 2003) – it becomes apparent Caryatid Encounters is more like a Greek tragedy: despite, or maybe because of all her efforts and energy, we know that her attempts at satisfaction – whether work or relationships or finding a flatmate – are doomed. Even before starting work on her advert for Sanssouci (a place, ironically, whose name means ‘without worries’ in French), she is told she won’t have proper access to the building and will have to work with a limited budget, sabotaged with a smug smile. “I have a job,” Helen defensively asserts to her sister over the phone, casually boasting how well paid the gig is and how much she’s enjoying it – and then eventually asking to borrow money.

Part of the impact of Caryatid Encounters is its unrelenting precision in portraying the theatre and anxieties of freelance life. Despite freelancing being an increasingly common way of working, particularly in the piecemeal realm of artistic and creative endeavours, its mechanisms – the constant performing of a professional self and submissions to chance – are often hidden away unshared. Media theorist Gary Hall, in The Uberification of the University (2016), describes the type of individual shaped by the gig economy, each having to act as ‘freelance microenterprises’: ‘self-preoccupied, self-disciplining’ people who have ‘lost the ability to plan and control their own futures. Consequently, they remain personable and positive, even when their way of life is rendered poor and precarious.’ Which seems to describe Helen to a T, if a bit perfunctorily; for any freelancer (ie, most artists and those involved in the ‘creative economy’, like art critics), that’s also pretty-long-ago ingested and rehearsed to the point of being self-evident. Which is maybe why Aiello’s video feels so unsettling, as it takes the self-preoccupied, self-disciplined state as a mood, a scab to pick at. Writer and ethnographer Heather Berg’s more recent Porn Work: Sex, Labor, and Late Capitalism (2021) is more insightful on the slippery nature of freelance work and exploitation, taking pornographic acting as a site to explore precarity, affective labour and the contradictions of the late-capitalist refrain to ‘do what you love’. One chapter explores the issue of authenticity, and the way that porn actors are meant to be believably seen to be enjoying their labour on camera. Berg opens the chapter with a reference to a video by actress and podcaster Sovereign Syre, who proposes the “the porn performer as a quantum mechanic”. Citing the thought experiment of Schrödinger’s cat (which was proposed to allegorically illustrate the paradoxical tendencies in quantum mechanics, wherein a cat trapped in a box could be simultaneously both alive and dead), Syre poses porn work as a quantum state: “The script, the performers, the setting, everything about it is false, and yet you’re expected to generate an authentic experience, like the orgasms are meant to be real… and the sex that’s happening is real… [Porn performers] are expected to perform two functions at the same time, to be incredibly theatrical and at the same time incredibly authentic… What’s considered a good performer in this context is actually someone that isn’t performing but in fact having real experiences.” This quantum state seems to reflect on Helen’s predicament, and by extension all those working under precarious gig conditions: a state in which she both does and doesn’t make a living from her work, does and doesn’t love what she does, can and cannot just be herself.

So what can she, or we, do about this? In researching her ad for Sanssouci, she surrounds herself with images of caryatids, covering her walls and desk, becoming drawn into one of the stories told about the origins of the Ancient Greek architectural feature, where the women of Karyai were paraded through the town after its capture and cast into stone as a threatening reminder. “They weren’t just carrying the weight of the structures,” Helen vents to a friend over for dinner, “but eternally carrying the weight of maintaining the social order.” Like most effective tragic figures, Helen becomes aware of her fate, sensing through these female columns her own role in supporting the structures that have caught her in this relentless performance: “Architecture is like a warning,” she says, prophetically, but one too late to heed. Her bleeding thumb from nervous scratching is just a corporeal reflection of her sacrifice to the infrastructures she inadvertently maintains as a woman, as a worker, as a ‘creative’.

And yet, perhaps in an all-too-apt reflection of freelance life, Caryatid Encounters offers no resolution; it starts all over again in an uneven loop of stymied apartment tours and manically cheery grovelling for more work, a cycle that seems frustratingly inevitable. If there’s any way out, it’s a problem that’s left to us. At the installation of the video in London’s Arcadia Missa gallery last summer, after watching the video you’d pass by the sculpture Welcome to her Counting House (2021), a plinth topped with two tea towels covered in uneven columns of cookies. They look unappetising: dried out, crummy and burnt. And of course, as an artwork, you’re not meant to actually touch them, much less eat them; but it’s presented as if taking a cookie might at least diminish these towers, might start to dismantle the architecture. Aiello poses a possible state where you both do and don’t eat the cookie: either way, you’re screwed.