From 2018: As an art critic, Indiana was big-brained and bitchy, literary and worldly

Gary Indiana isn’t an art critic any more, hasn’t been one for decades. But in the prefatory essay to this chronologically organised collection of his art writing for New York’s Village Voice – as the present-day novelist and memoirist looks back on the fragile, fervid, quickly gentrified ecosystem that was the East Village art scene during the early 1980s – we get an instant sense of how he carried himself in those days, and of the world in which he operated. A gallerist, Gracie Mansions, asks what he thinks of one particular work. Finding it ‘very disagreeable’, Indiana tells her it’s a piece of shit. ‘She whooped. “I don’t think it’s the worst piece of shit,” she said. “You should see who I’m showing next, you wanna see shit.”’

A few pages on, it’s 1985. Indiana is now on the Voice’s masthead and covering the whole of New York (and beyond) while toting the same vinegary attitude, and he’s considering Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981). Reckoning that the only argument in favour of this ‘hateful’ sculpture is that it might enlighten working stiffs to the coercive architecture around them, Indiana suggests that such a wised-up audience ‘would then proceed to demolish the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building, the disgusting turquoise fountain in the plaza, and stop going to work’. Failing that, ‘perhaps the answer is to sell [Serra] the entire building complex for a dollar, and let him pay taxes on it’.

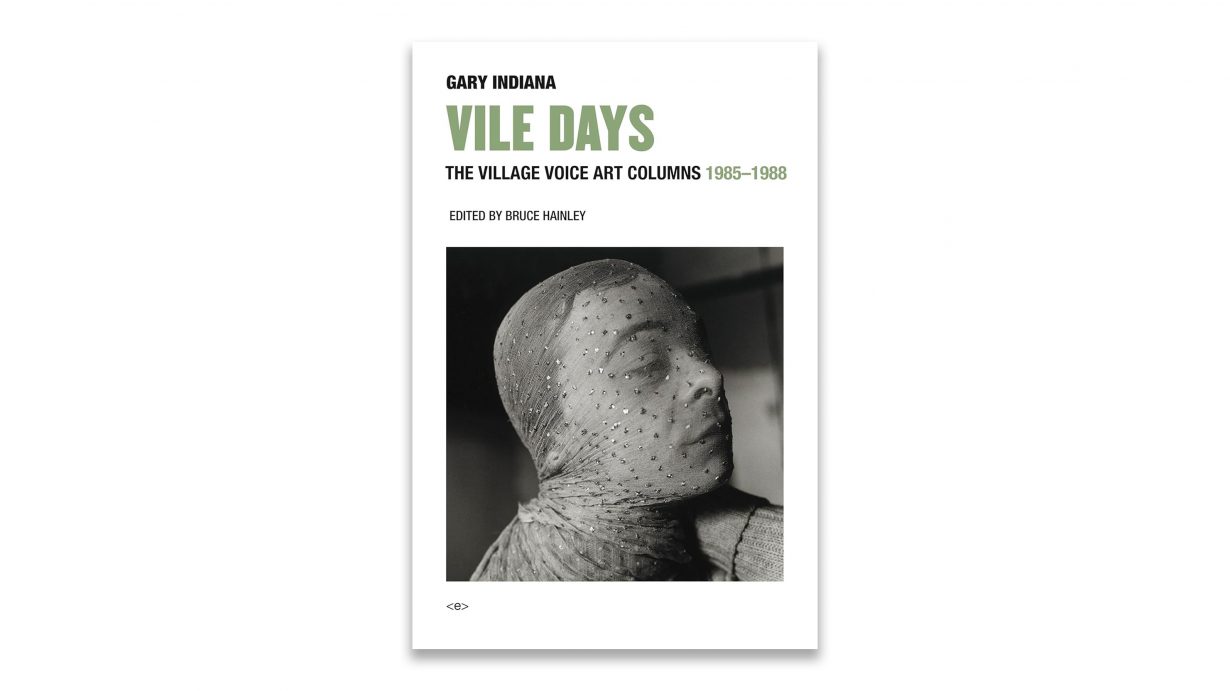

As an art critic, Indiana was big-brained and bitchy, literary and worldly, indifferent to decorum and apparently cognisant that he wasn’t in this for the long haul, having novels and plays to pen soon enough. The cultural reassembly Vile Days represents was performed by critic Bruce Hainley, who typed up the archival texts and has himself expressed frustration with criticism as it stands today; this is how, at best, it stood yesterday. And despite the title’s signalling of Indiana’s attitude to the big-shouldered period covered, he in no way exclusively singles out things he despises. He sees, for example, Gerhard Richter’s then-new acidic abstractions and landscapes (in the latter, the artist ‘handles paint like a master violinist playing third-rate chamber music at a formal tea ’), and immediately clocks their ‘startlingly direct interrogation of the notion of sincerity in the work of art’. In general, official history has been kind to his on-the-spot assessments; we’ll agree to disagree about the Starn Twins.

The columnist’s curse is finding something to write about every time, and Indiana’s beat had its dry spells. In 1988, following the stock market crash – in whose aftermath he writes a piece querying the apparently then-widespread assumption that in a fallow market, critics have more power – he goes to a Sotheby’s auction of Warhols, ‘a full-blown fire hazard of elderly women with no wrinkles and men with no lips’ . He decamps for the Venice Biennale, where he reviews some American warships docked nearby. He picks up on whatever’s shaking the trees among the art cognoscenti, for instance an apparently naive and biased Janet Malcolm profile of Artforum’s then-editor Ingrid Sischy. At one point he reviews the art placed in Manhattan bank lobbies, making up for it with a tour-de-force pseudo-philosophical delineation of the escalating stages of being ‘pissed off ’. And he tinkers restlessly with form, phrasing his columns as letters, diary entries, interviews, giving up taking notes in shows and making drawings instead.

Vile Days is of course a time capsule, measuring the distance between a sifted, historicised 1980s and the actual 1980s, which was as full of art by future filmmaker/actor Vincent Gallo, Gretchen Bender, Mike Bidlo and Meyer Vaisman as it was of works by Jeff Koons, Peter Halley, Barbara Kruger et al. The info-dump format here (only one essay missing; at Indiana’s behest, says Hainley) means you’re frequently reading historical pronouncements on artists and occurrences history has sidelined; the upside is that you feel embroiled in a neon-bright, eventful, messy historical moment, conducted through it by a low-life Virgil, until – goaded by boredom, structural disappointment and hate mail – he’s done. ‘This is my last art column for the Voice,’ he begins a 1988 piece on Felix Gonzalez-Torres that necessarily revolves around the AIDS crisis. ‘Take it or leave it. I’ve had my fun and now it’s time to do something else.’ Take it.

This article was first published in ArtReview October 2018