A new book, Gauguin and Polynesia, revisits the painter’s controversial period and the ‘archive of colonial imagery’

‘Gauguin is always poaching on someone’s ground; now he is pillaging the savages of Oceania’, sniffed Camille Pissarro in 1893. Which goes to show that the imputation of cultural appropriation levelled against Gauguin – in kind, if not by name – goes back to the very first moments that the painter’s impressions of Polynesia began to arrive in Parisian galleries. Subsequent generations rehabilitated him, invigorated by a heady concoction of formalism and the modernist mythography of genius (‘his faults are accepted as the necessary complement of his merits’, W. Somerset Maugham declared of his thinly veiled cipher for Gauguin, Charles Strickland, in The Moon and Sixpence, 1919). Yet in our own day, Pissarro’s charge of theft has returned, redoubled by concomitant accusations of paedophilia and of the introduction of syphilis to the South Seas. It’s hard to utter Gauguin’s name now without a kind of apologetic wince – and yet, we do keep uttering it.

With his new book Gauguin and Polynesia, Nicholas Thomas explicitly does not set out to offer ‘a new vindication of Gauguin’, and so he commits to walking a very narrow rope. By its very appearance, the book runs the risk of incurring sighs from some quarters and hurrahs from others, and both for precisely the same reason. Here is an expansive and meticulously researched account of Gauguin’s life and art, before and during his fateful excursions. Surely, then, it must be advancing the case – and resuscitating the furore occasioned by Griselda Pollock’s extended excoriation of 1993, Avant-Garde Gambits – for rescuing the formal brilliance of Gauguin’s paintings from the ethical questions prompted by what we know of his character?

What Thomas is actually doing here is altogether more subtle. As director of the Museum or Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge and an expert in Polynesian art, he is unusually well placed to tell us about the kind of society Gauguin would have encountered in the 1890s – and as such, to attempt to properly establish the vexed relationship between myth and reality that is such an integral part of the paintings, complicated both by Gauguin’s own self-mythologising memoirs Noa Noa (1901) and Avant et Après (1903) and by the way that this aspect of his work has been seized upon by advocates and detractors alike. The blockbuster exhibition Gauguin: Maker of Myth, which premiered at Tate Modern in 2010, made the case that the artist’s engagement with myth amounted to a rear-guard effort to reinstate narrative at the heart of modernism; for Pollock and other critics such as Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Gauguin’s depictions of Polynesia were nothing short of a racist, colonialist fantasy.

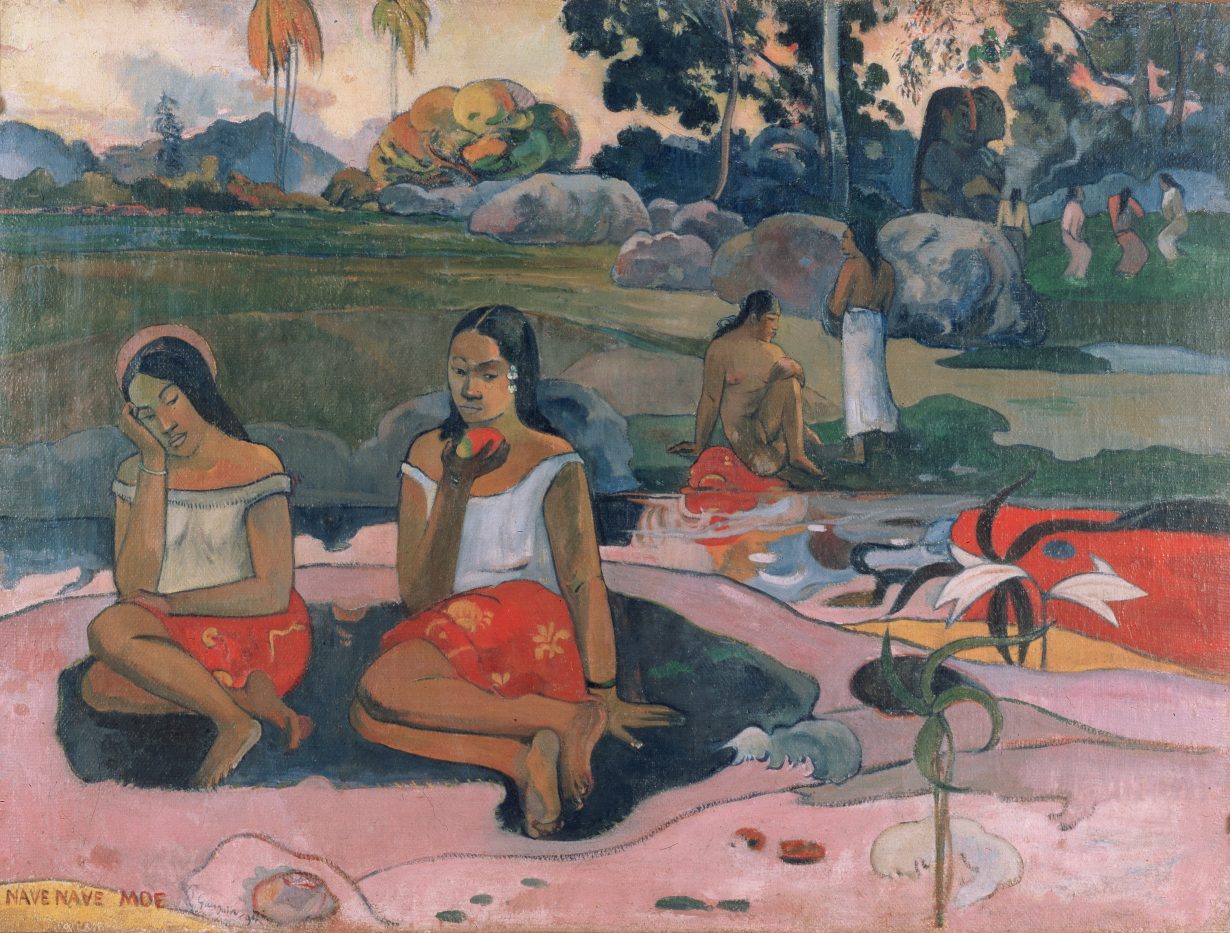

Much of these critics’ arguments centred on the suggestion that Gauguin’s paintings turn a blind eye to the fact that Polynesian culture had been ‘effectively destroyed’ by Western influence long before he arrived. To this, Thomas gives short shrift. Consider, for instance, the muumuu – a long-sleeved robe, once known as a Mother Hubbard, that was brought to the Pacific in the nineteenth century. Solomon-Godeau called them ‘hideous’, Pollock ‘the shapeless sack inflicted on Tahitian women by missionaries’ – but Thomas convincingly points to the ‘value that fabric and dress possessed in Tahiti and elsewhere in Polynesia before and after colonization’ to make the case that, in fact, Islanders were motivated to adopt Western dress for their own reasons, and that doing so could be an expression of agency. That Gauguin tended to depict women in pareus – fabrics, frequently tied at the waist and worn without a top – doesn’t prove that he preferred women ‘in little or no dress at all’, as one critic has had it; Thomas suggests, instead, that the ‘archive of colonial imagery’ skews the record, since women were more likely to be photographed in their formal long dresses, but they would not have worn these every day. Damningly, Thomas links the conviction that the muumuus themselves were ‘aesthetically dreadful’ back to ‘disparaging observations by colonial travellers made as long ago as the 1820s’.

All of which is to say that, whether you are a fin-de-siècle painter or a critic in the 1980s, engaging with the reality of distant cultures is always fraught, and it’s in this sense that Thomas is perhaps most sympathetic towards Gauguin. Although, especially in his written work, Gauguin ‘was undoubtedly captive to stereotypes of the exotic and the primitive’, Thomas finds in many of his portraits of Tahitians a sincere engagement with – or at least, a reflection of – unfamiliar forms of power and sovereignty.

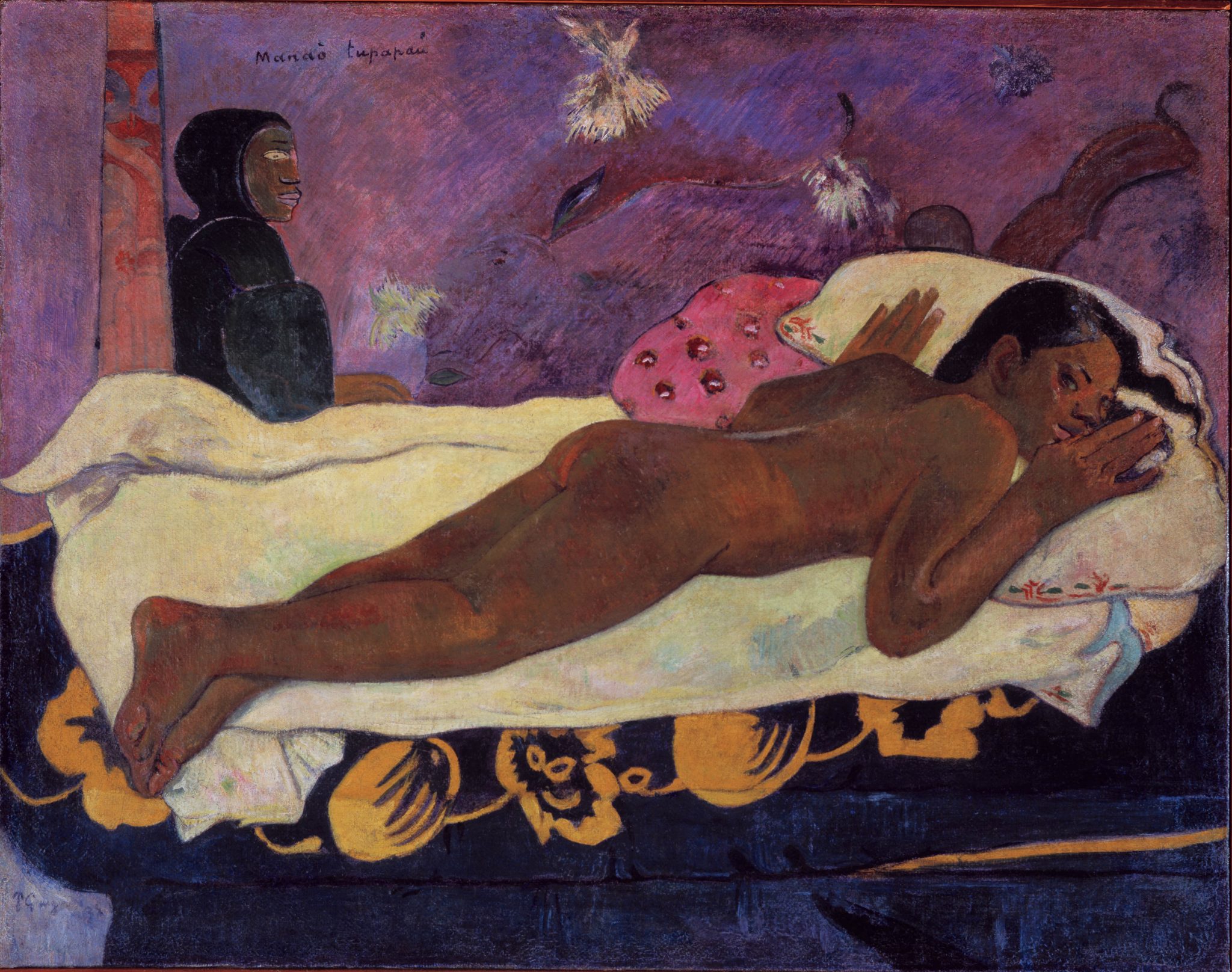

But Thomas is true to his word: this isn’t a defence of Gauguin, and he is just as effective in pointing out Gauguin’s misapprehensions, wilful or otherwise. So, in his extended close reading of Mana’o tupapa’u (1892) – the painting that has divided interpretation perhaps more than any other – Thomas argues that Gauguin’s stated efforts to express the islanders’ belief in ‘the spirits of the dead’ reduces them to fearful ghosts, neglecting any appreciation that the ancestors could ‘lend strength and mana, spiritual power, to their descendants’. This is a fine point to pull him up on, when compared with, say, Stephen Eisenman’s declaration that ‘The picture and the artist’s written account of it appear a veritable encyclopaedia of colonialist racism and misogyny’. But even in giving Gauguin the benefit of the doubt – assuming that Gauguin was trying to convey something of Tahitian spirituality, and not just paint a voyeuristic nude of his underage wife – Thomas shows that he has only succeeded in travestying them.

Where does this leave us? As far as Gauguin is concerned, his work is ‘contradictory in the deepest possible sense… the question of whether it is in the end somehow affirming, or irretrievably pernicious is beyond resolution’. That might feel a touch overly diplomatic – but then, it’s the ability to negotiate such a wide array of voices and critical standpoints that, in the final analysis, makes this book such a valuable contribution to art history. Thomas never condemns the aims of what Pollock or Solomon-Godeau were trying to do, in advocating the social history of art as a means of looking beneath the surface of the paintings and understanding the dynamics of power at play in their production and reception. In many ways, he is picking up where they left off – though from a vantage-point that is tempered and nuanced by an appreciation of the inherent messiness of the colonial encounter and the ways in which colonised peoples asserted their agency throughout it. In that sense, the methods of Gauguin and Polynesia mirror its subject: the book is a meeting place of perspectives, in which Gauguin becomes just one actor among many.

Gauguin and Polynesia by Nicholas Thomas. Apollo, £40 (hardcover)

Samuel Reilly is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of St Andrews