A new graphic biography of the revolutionary author suggests that we shouldn’t separate the writer from the writing

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil is someone about whom you’ve most likely never heard. Her pseudonym, George Sand, is another case altogether. Assuming you’re into bestselling nineteenth-century European literature. Or women who fought the social conventions of gender. As this graphic biography (Consigny is the illustrator) makes clear, Dupin/Sand was pioneering in relation to both. Although these days there’s more interest in the second. Particularly here, where the visible signs of her play with gender norms (tying up or hiding her hair, smoking and wearing men’s clothes in public – the last, at the time, illegal – and generally living like a man) are most easily reproduced. But despite that, and to its credit, this book suggests that we shouldn’t separate the writer from the writing in this way. Sand’s written works appear or are referenced almost as often as her lovers (of which there were so many, it at times seems as if Consigny has run out of sufficiently distinct male types to easily separate one from the next; although such confusions in turn might simply reflect how things were at the time).

Sand’s politics are formed at an early age. Her father died when she was young and consequently she was raised by the females of the family. Her father’s family was rich; her mother’s poor. She was brought up by her paternal grandmother, who believed in education; her mother, despite her poverty, believed in fashion. They, for the most part, hated each other. Sand’s belief in equal rights began at an early age and survived (or perhaps blossomed as result of) both a convent education and an abusive marriage. Life, for Sands, was lived physically (riding, travelling) and intellectually, just as love was always physical as much as intellectual. Even Charles Baudelaire, a poet and contemporary whose life was famously dedicated to intoxication and pleasure, found Sand shocking: ‘that there are men who could become enamoured of this slut is indeed a proof of the abasement of the men of this generation’, he wrote. Writers like Proper Meerimée and musicians such as Frédéric Chopin, on the other hand, chose to be enamoured and to become Sand’s lovers; as, according to this biography, did the actress Marie Dorval. At least they did until Sand moved on to the next thing, which might not mean the end of the old thing. Whether that thing was a lover, a text or a political cause. Given this mix, the graphic format proves particularly appropriate to capturing this unusual, revolutionary life.

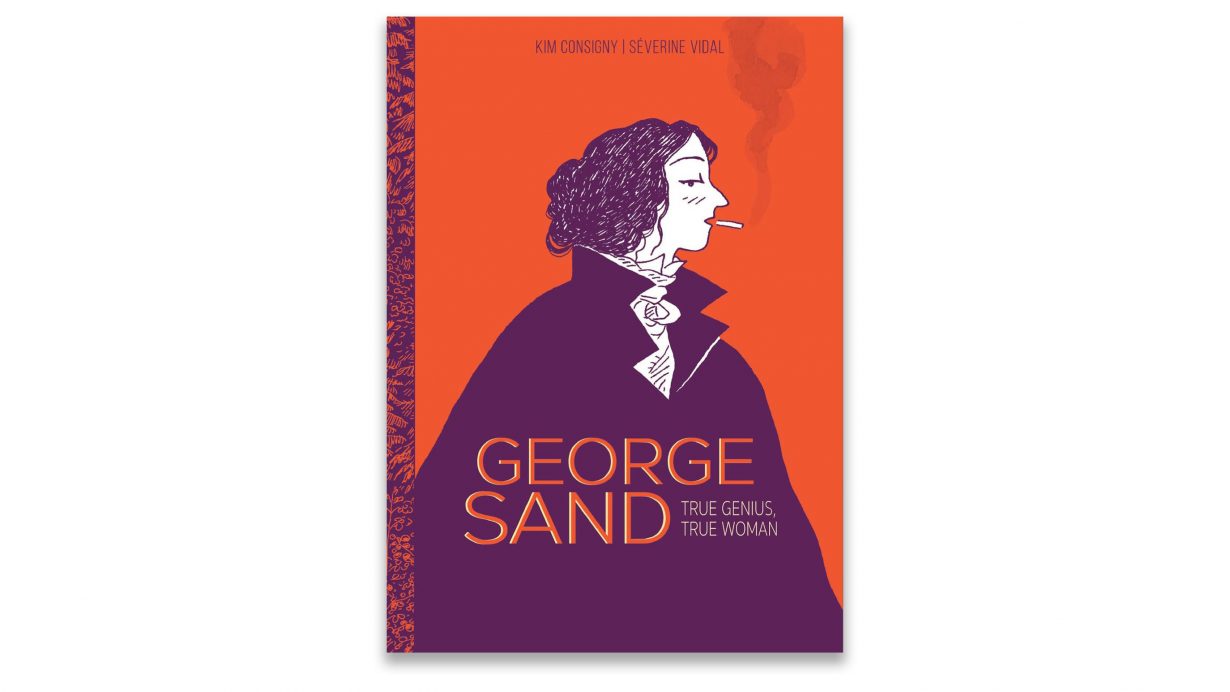

George Sand: True Genius, True Woman by Séverine Vidal & Kim Consigny, translated by Edward Gauvin. Self Made Hero, £18.99 (softcover)