An exhibition at Kunstmuseum Basel frames the ghost as a ‘call to attention’ that interrupts temporal continuity and insists upon the unfinished work of history

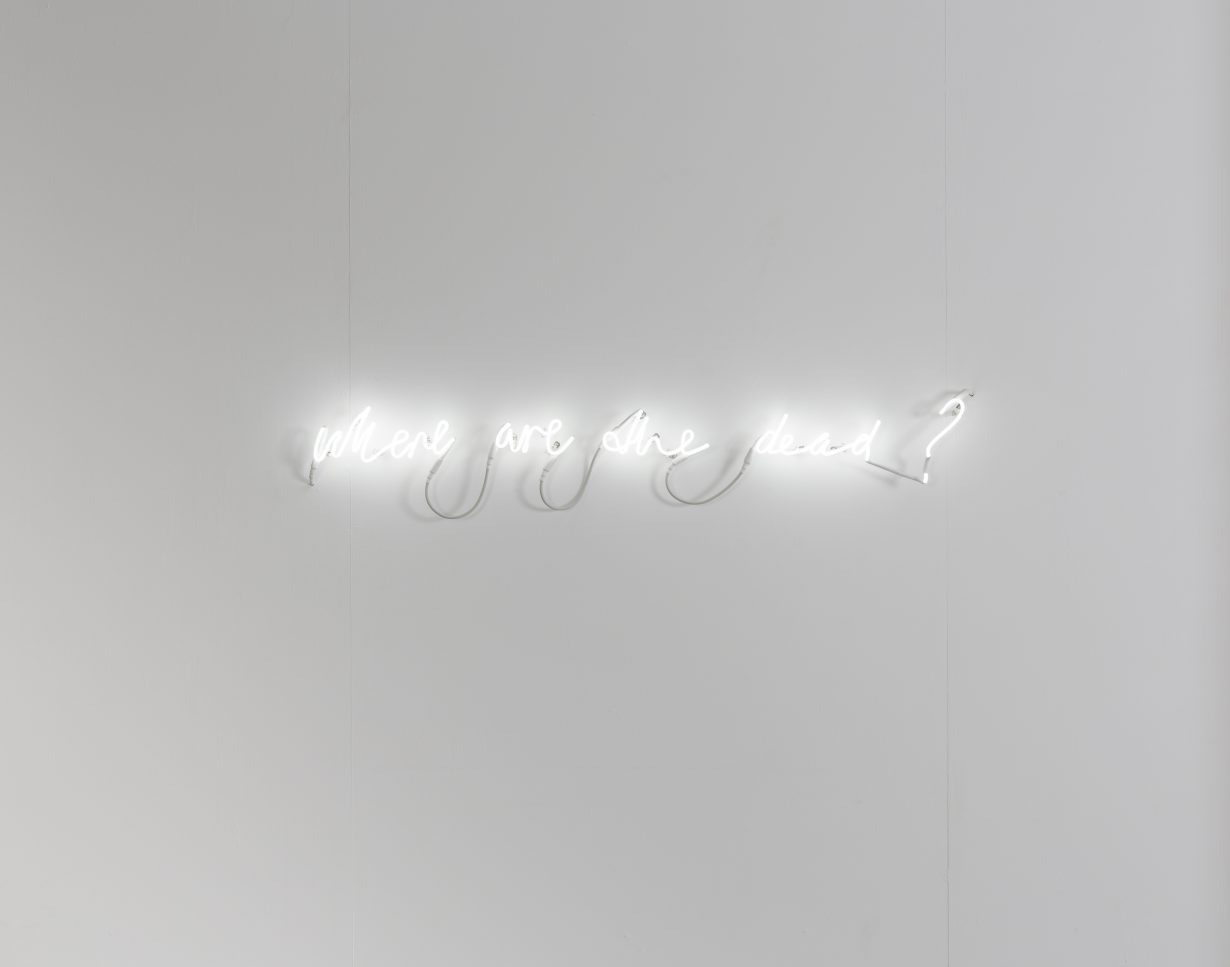

Tracing its subject from 1777 to the present via more than 160 artworks and ghost-related artefacts across nine rooms, Ghosts: Visualizing the Supernatural poses a deceptively simple question: ‘What do ghosts have to say to us?’ It’s a simple premise but it risks collapsing a history of spectres, psychological disturbance and cultural superstition into a generalised metaphor for human projection.

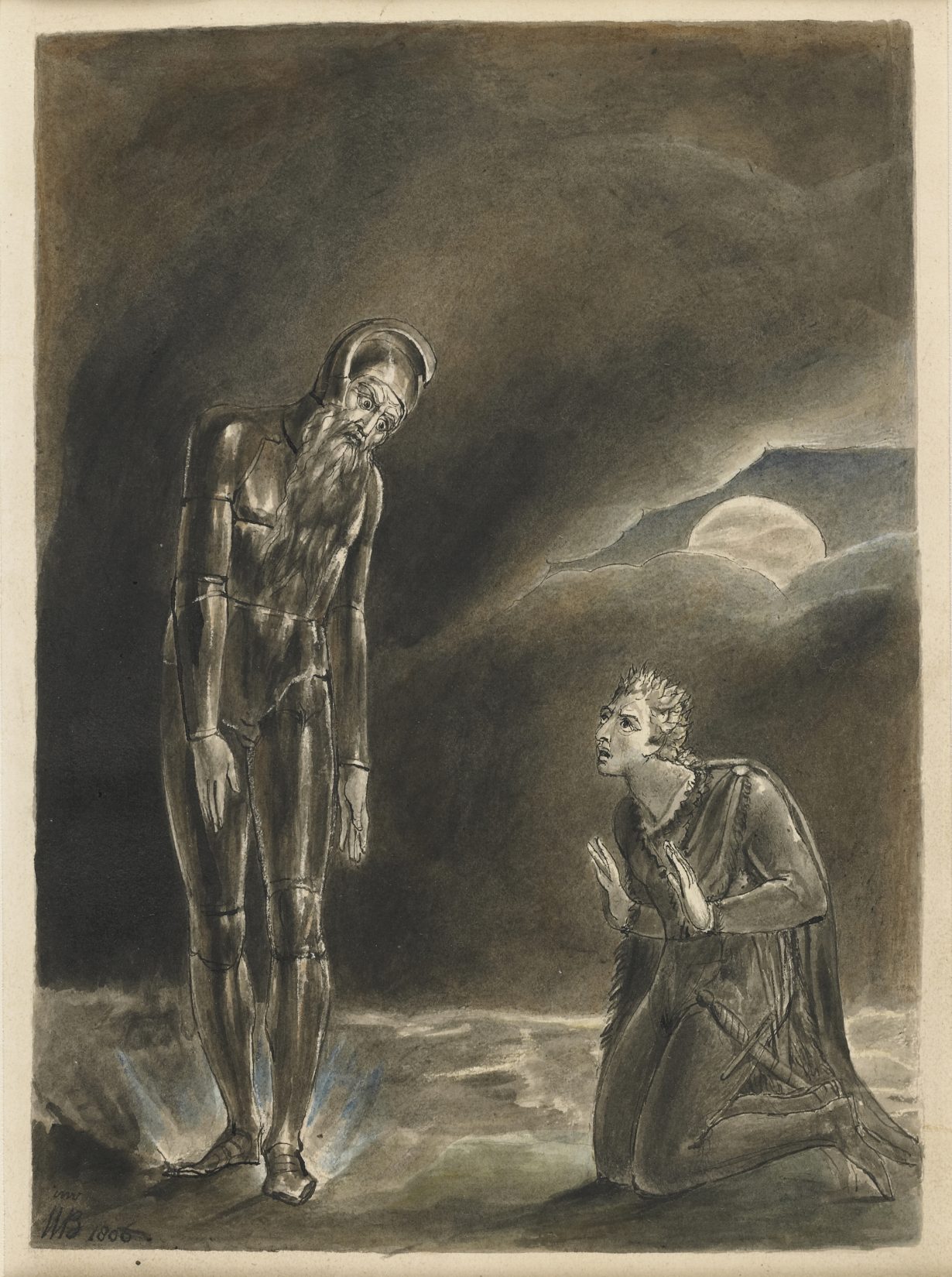

A sheet-draped mass, resembling the traditional burial shroud, acts as the mascot for the exhibition. We first encounter the form in Katharina Fritsch’s Gespenst und Blutlache (1988), a narrow two-metre-high apparition positioned in the entranceway to the first room, where the nineteenth-century projection-based illusion ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ – developed by scientist John Henry Pepper – manifests another draped figure, underscoring the theatrical mechanics of Victorian apparitions. What follows is a broad chronology of artistic interpretations of spirits through the centuries, from Benjamin West’s painterly depiction of an early ghostly narrative (Saul and the Witch of Endor, 1777) to William H. Mumler’s spirit photographs, such as Mary Todd Lincoln with the Spirit of Her Husband, President Abraham Lincoln (1870–75). Here the show positions ghostly presence somewhere between transcendental experience and antiquated scientific experiment.

1806. Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel

Courtesy CONNERSMITH. Washington, DC © Susan

MacWilliam.

As the exhibition shifts from spirit documentation to the interior turmoil of psychic disturbance, the line between observed phenomena and the evidence of a disturbed individual become unhappily blurred. Twentieth-century anthropologist Eric Dingwall’s ‘Ghost Hunting Kit’ scans sinisterly alongside the drawings of visionary spiritualists Georgiana Houghton, Madge Gill and Maria Hofman, artists who correspond to Hans Prinzhorn’s notion of the ‘schizophrenic master’ in his book Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922). The bodily fragmentation in these images suggests that attempting to visualise the supernatural overwhelms the capacity of known or received norms in artistic form.

From exemplars of the haunted psyche, Ghosts then pivots to contemporary artists drawing overt inspiration from outsider art. Rachel Whiteread’s Poltergeist (2020), a white shed in tatters made from white-painted iron and wood, mirrors the torn-apart furniture of Urs Fischer’s Chair for a Ghost: Urs (2003), both linking psychic fracture to physical disturbance. A subsequent room surveys twentieth- century approaches, ranging from René Magritte’s paper cutout ghoul The Comical Spirit (1928) and Toyen’s The Pink Specter (1934) to Mike Kelley’s Ectoplasm Photographs (1978/2009). Particularly incisive here is Rosemarie Trockel’s Der direkte Draht zum Jenseits (1988), a minimalist Ouija board that situates the waning of religious belief alongside modernist scepticism: a wire line linking the letters ‘JA’ and ‘NEIN’ signals Trockel’s resentment of the numinous. In the final rooms, the show zooms in on the haunted-house motif. Shown alongside Corinne May Botz’s Haunted Houses series (2000–10) – photographs and texts from haunted sites across America – is Cornelia Parker’s PsychoBarn (Cut-Up) (2023), a deconstructed replica of the Bates Motel from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

The thin line that Ghosts draws between the inspired, the pathological and madness, and its critique of Spiritualism’s extractive tendencies, might have been more apparent through more cross-historical pairings and juxtapositions in what is otherwise a chronologically organised show. Throughout, Ghosts frames the ghost as a ‘call to attention’ that interrupts temporal continuity and insists upon the unfinished work of history, best exemplified in three paintings of Hamlet’s ghostly oedipal encounter by Eugène Delacroix, William Blake and a copy after Henry Fuseli. The writer Mark Fisher’s reading of hauntology as the return of lost futures suggests that ghosts do not simply represent the past, but the persistence of what could have been. In tracing a sheet-draped form across centuries, yet only examining it cursorily as a site of reenacted trauma or the unheimlich, Ghosts misses an opportunity to interrogate the spectral as both historical residue and political metaphor.

Ghosts: Visualizing the Supernatural at Kunstmuseum Basel, through 8 March

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.