In his new book, David Joselit offers a convincing description of the global and historical dynamics that produced ‘contemporary art’ as something distinct from what preceded it

What David Joselit offers in Heritage and Debt (2020) is a convincing description of the global and historical dynamics that produced ‘contemporary art’ as something distinct from what preceded it. For most observers of art and its history today, that question would be answered with some combination of ‘postmodernism’ and ‘modernism’, which is not incorrect. But on Joselit’s account, that answer is both woefully incomplete and politically compromised.

Prior to 1989, the global economic order was divided into a hierarchy (as the West saw it) of three different worlds: the advanced capitalist economies of the first, the socialist economies of the second and the developing economies of the third. Joselit’s first innovation is to identify each of these worlds with its own aesthetic ‘idiom’: a ‘modern/postmodern’ idiom for the first world, a ‘realist/mass cultural’ idiom for the second world and a ‘popular/indigenous’ idiom for the third. The first world valued its own idiom above the others, whose products it collected, or dismissed, as artefacts, decoration or kitsch.

As a second innovation, Joselit proposes a ‘deregulation of images’ paralleling the economic deregulation that began in the West during the late 1970s, accelerated during the 1980s and went global after 1991 with the Soviet Union’s collapse and China’s rise. Joselit’s deregulation entailed postcolonial practices of indigenous artists, socialist realism from China and the USSR, and underground art from Soviet bloc countries and South America claiming equal status with first-world fine art, in both exhibitions and sales.

What Joselit calls the ensuing ‘recalibration’ of aesthetic value and recognition is conducted through the marshalling of ‘heritage’: inherited cultural resources and properties that are available not just to those within a specific culture but to everyone. Importantly, Joselit describes ‘heritage’ as a ‘set of living traditions’ whose ‘invocations’ do not ‘inherently possess a specific political valence, either conservative or progressive’, but whose ‘potential lies in the negotiation… between heritage and perceived debts to “one’s own” cultures and those of others’. When cultural heritage is ‘synchronized’ in and with the present through strategies of ‘appropriation’, ‘pastiche’, ‘reframing’ and ‘curation’ – all definitive strategies of global contemporary artistic practice – it leads either to art’s ‘financialization’ (bad) or to new forms of ‘authorization’ (good). Either way, the dynamic of idiomatic deregulation and the synchronization of cultural heritage in the present is what produces the phenomenon, and our period, of ‘global contemporary art’.

This is surely right. As history it integrates and coordinates the geopolitics of ‘globalization’ with diverse practices: Joselit includes close readings of Jeff Koons, Ai Weiwei, Shahzia Sikander and Raqs Media Collective, among others. As theory it does for the ‘cultural logic’ of contemporary art what Fredric Jameson did for postmodernism. But as an ethics and politics of art practice and history it is less convincing.

Putting aside Joselit’s hyperbolic demonisation of the market and art’s financialisation, his prescription for ‘art’s progressive politics’ ultimately turns on one favoured concept, ‘authorization’, which is too capacious to do the job meant for it: progressively minded subjects must ‘authorize’ themselves; every artwork must itself be ‘authorized’; the ‘meaning’ of images is determined by the ‘social and geopolitical conditions’ under which they are ‘authorized’ to appear; aesthetic strategies are ‘differently authorized in different parts of the world’, and so forth.

When Joselit does explicitly state what he means by ‘authorization’, he calls it ‘a provisional situational seizure of a quantum of meaning as legitimately one’s own’ (my emphasis). One could be forgiven for thinking Joselit was talking here about Twitter or Instagram rather than laying out the programme for a ‘responsible history of global contemporary art’. The question of course is, ‘Who decides what’s legitimate, and how?’ But this goes unaddressed in Joselit’s account. ‘Legitimacy’ is a problem not just for art history and criticism. It is the crisis faced by the global north today, politically (with neoliberal democracy threatened from both right and left), socially (with the reckoning of racism and colonisation) and economically (with the rise of authoritarian capitalism). But perhaps these are questions for Joselit’s next book.

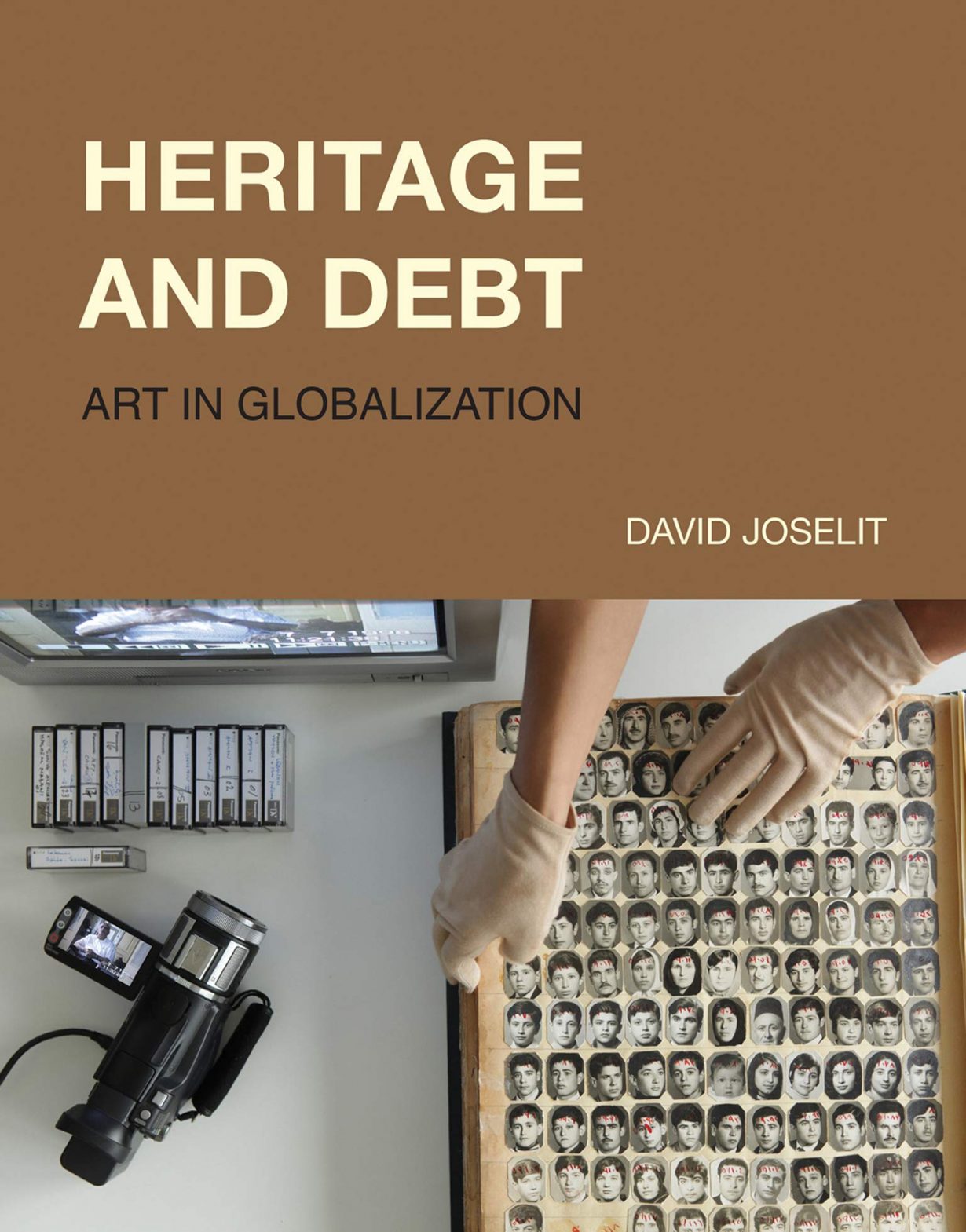

Heritage and Debt: Art in Globalization by David Joselit, published by MIT (October Books)