In his canvases, time and place become fluid, and all kinds of ostensible givens are undone in real time

Eleven years ago, Michael Armitage was a student in London’s Royal Academy Schools; now he has a solo show in the Royal Academy itself. The last time he exhibited in this building, it was at the end of what he calls a “difficult but fundamental” postgraduate course during which he broke down and rebuilt his approach to painting, moving from abstraction back to figuration and beginning to work on the rough Ugandan bark cloth, lubugo, that’s now an integral part of his art. Returning to the fabled institution on Piccadilly, Armitage is presenting a minisurvey – Paradise Edict, which originated at Munich’s Haus der Kunst – extracting 15 paintings from his last seven years’ work, during which time he joined White Cube’s roster, had solo exhibitions from the Norval Foundation in Cape Town to MOMA in New York and alternated his base between Nairobi, where he was born, in 1984, and London. It’s a lot for one person to process; which is perhaps why, when Armitage pops up on my laptop screen, he appears to be sitting peaceably in a secluded cave.

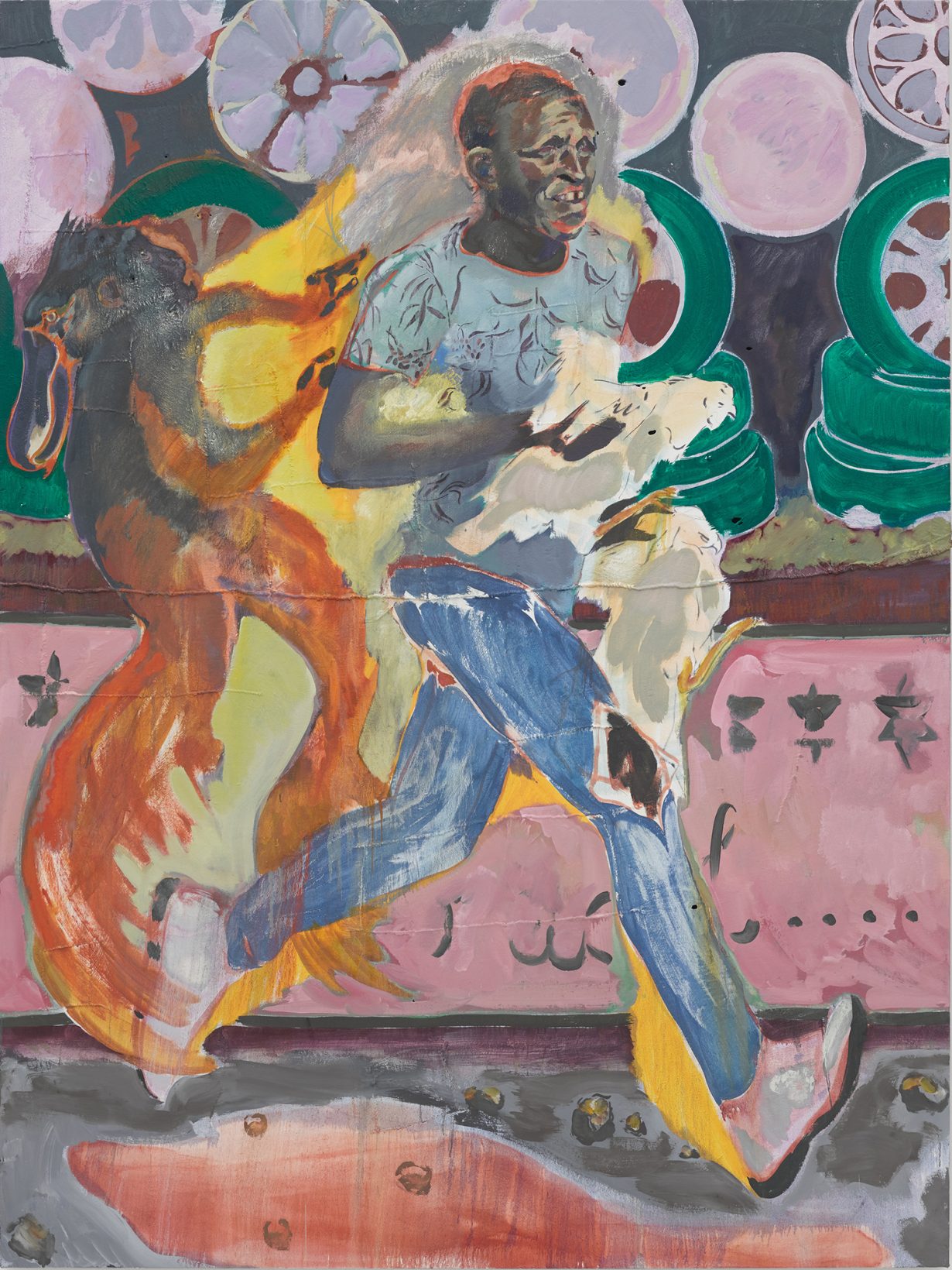

OK, it’s just his Zoom backdrop, and Armitage is actually settled in a leather wingchair in his London studio; but the cave, Armitage clarifies, is an African one, underscoring the centrality of the artist’s homeland to him. Kenya is the grounding locale of his luminous yet opaque paintings, which merge imagery and influence from a range of sources – the East African artists he encountered in his youth; European greats such as Gauguin, Goya and Titian; mythology, rumour and contemporary political events. In his canvases, time and place become fluid, and all kinds of ostensible givens are undone in real time.

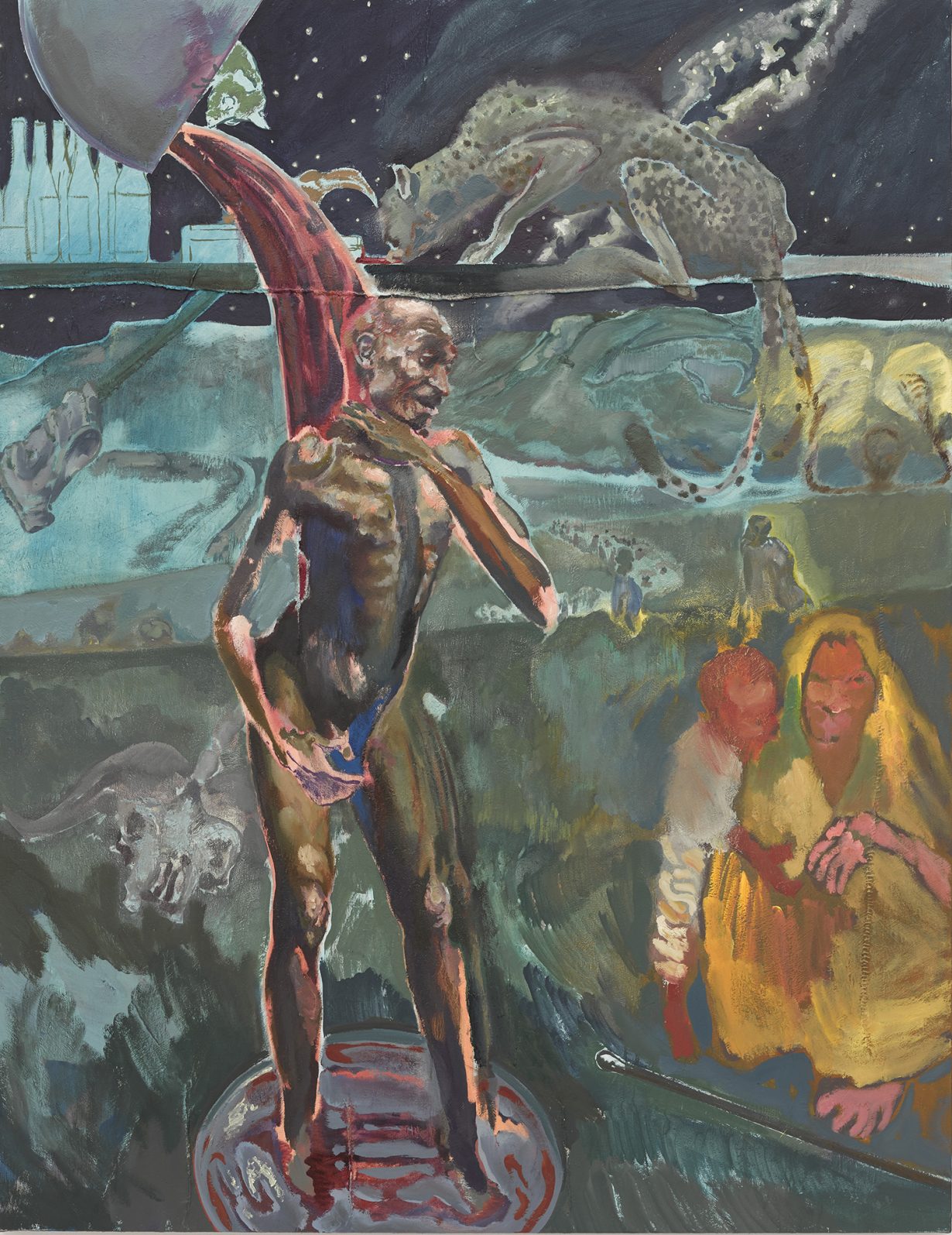

One of the paintings in the RA show, for instance, Mydas (2019), originated in Armitage’s reading of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. King Midas has become a shorthand for greed, “but he’s probably one of the most hopeful figures in the whole book”, says Armitage; Midas ruled a drought-stricken land, and wanted to turn things to gold so he could feed his people. Armitage’s composition, driven by El Greco-ish wristy bravura, locates the moment in the story where the king, after being told he’ll get what he wants if he bathes in wine, is showering his thin black body in ruby booze against a star-dappled sky. The backdrop is a convergence of ghostly figures, fragmentary aquamarine landscape based on Armitage’s in situ drawings of an arid, drought-plagued region of contemporary northern Kenya, a wine-lapping cheetah and murky abstract elements open to interpretation. The painting asks you to traverse it while pinning itself, in symbolic fashion, to a story that many only know as a distortion.

Armitage’s paintings arise, he says, “whenever there’s something that presents itself which, to my mind, I feel like I’m unresolved in”. In 2017, relatedly, he inveigled himself into a TV crew filming an opposition party rally in a Nairobi park during the 2017 general elections in Kenya. This led to paintings such as The Fourth Estate (2017), with a cluster of figures sitting in an empurpled tree unfurling a picture of a frog, while the branches quiver lyrically in the wind. If it’s likely many of Armitage’s viewers won’t grasp the details here, it’s also not important to him, since he’s operating in a space where issues of unmitigated truth – for instance, in journalistic coverage of elections – are already open to question. For him paintings aren’t legible hubs of connotation so much as spaces of charged, freeform encounter in which much of what transpires is nonverbal and subjective. This is an artist, after all, who cites as one of his most important exhibition experiences an El Greco show in which he ignored all the wall labels and so had little idea of the religious content of the works. “Paintings just don’t have any meaning,” he says. “They are what they are, unless you allow them to have that for you. And then they can be extraordinarily profound. But in many ways it’s like trying to talk about, let’s say, Formula One but only having the language of fishing…”

Of course, one can make something of the fact that lubugo, whose rough texture redirects the artist’s hand and which in Armitage’s paintings is often pitted with holes, is also used for funeral shrouds; one can notice and thematise the animist equivalencing of humans, animals and landscape in his paintings. But the places where he wants to make definite assertions are, thus far, mostly outside of his painting practice. The son of a Kenyan mother and an English father, Armitage grew up in Nairobi – relocating to the UK when he was sixteen, later doing his undergraduate degree at the Slade. (Asked if he paints differently when he goes back, he deadpans, “Yes, with my feet”.) Last year he set up the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute in the city, a nonprofit ‘dedicated to the growth and preservation of contemporary art in East Africa’. The NCAI cocurated a vital auxiliary section in Paradise Edict that functions as a minisurvey of a half-century of figurative painting practice in the region via 35 works by six artists: Asaph Ng’ethe Macua, Elimo Njau, Jak Katarikawe, Theresa Musoke, Sane Wadu and Meek Gichugu. (This segment of the show will, at an as-yet-unspecified date, also be shown in Nairobi.)

“I had always been a bit frustrated with how a lot of the painters I grew up with and have been influenced by have been represented – in terms of colonialism and naive primitivism – and I knew how frustrated they were with these descriptions,” Armitage explains. “They were also part of a history, and saw themselves that way, whether it was political and cultural movements like Pan-Africanism or thinking about indigenous language.” As such, Armitage is using the cultural leverage he has to demonstrate that he’s not sui generis but part of a creative continuum, and also widening the spotlight. In a similar influence-revealing way, a simultaneous exhibition for the Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Account of an Illiterate Man, places his paintings in the context of a collection-riffling array of works, from a study for Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867) – a painting that Armitage says he’s looked at and thought about ‘thousands of times’ – to Egyptian mummies, paintings by Berthe Morisot, Goya and Gauguin, and myth-themed marble sculptures and painted shrouds.

In one section of the show, near etchings from Goya’s Los Caprichos (1799), is Armitage’s Hope (2017), depicting a serene-looking woman, gazing past the viewer, who has just given birth to a donkey, the umbilical cord still attached. This would be quixotic enough, but in the upper-right corner there appears, floating in a v-shaped prism of colours, a generic washing machine, while at bottom right a small black figure is either tumbling through space or just an illustration on a cushion. The painting is done, as usual, on bark cloth, small sections of it stitched together in a parallel to how the compositional elements collide different realities within structural surety. Ask Armitage how he begins to structure such ensnaring, wrong-but-right things, to move between cultural hierarchies of images and stories, and his answer suggests a sagacity that connects his art back to a grand tradition and, simultaneously, proffers an insight that eludes many artists who equate artmaking with encoding, rather than the refulgent and free act of looking. “Everything”, Armitage says simply, “is in the service of the painting.”

Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict can be seen at the Royal Academy of Art, London, through 19 September

Michael Armitage – Account of an Illiterate Man is on view at the Glyptotek, Copenhagen, from 6 June to 17 October