Sometimes the artworld is booming, sometimes it finds itself in crisis. The current moment of uncertainty prompted ArtReview to go back to its archives, to look for other moments when, for better or worse, the times they seemed to be a-changin’, even if it couldn’t always work out how, or why.

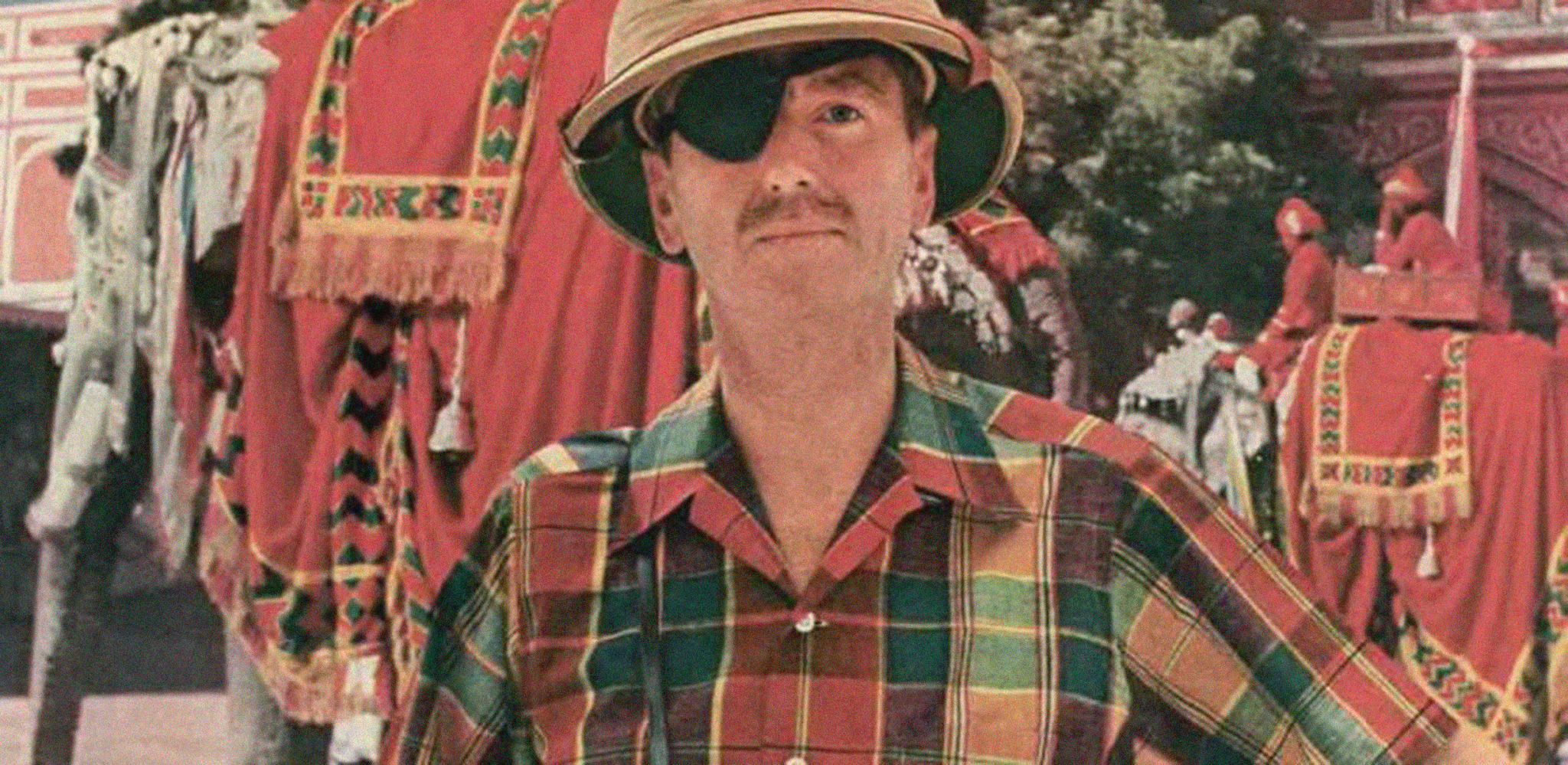

In this foray into the archive – the first of many for this new series – ArtReview puts on its NHS glasses and returns to the booming modern art scene of London in the (just about) Swinging Sixties. With artists selling out shows all around him, G.M. Butcher heads off to review the latest show of works by lauded sculptor Reg Butler. Distracted by shopping opportunities, bothered by gallery gossip, Butcher considers the growing phenomenon of artists turning out editions to satisfy a burgeoning art market…

Reg Butler at Hanover Gallery, London, reviewed by G. M. Butcher, Art News and Review, 18 June, 1960

I must begin by saying that my afternoon in London was ‘one of those days’, and everything that happened was calculated to arouse the spirit of cynicism. Those beautiful Madras shirts – “guaranteed to fade” – must be bought on the sole assurance that the famous shop concerned would never sell anything that wasn’t perfect. When asked if they didn’t – possibly – have a bit of laundered material, so that one could see what kind of effect the fading produced, I was solemnly assured, “We don’t, of course, do such things.”

With this behind me, I then spent several hours previewing the new Reg Butler exhibition. Everything was already very nearly in place, but the atmosphere was relaxed, and far from that almost religious hush which seems so often to descend upon the better galleries of London. Although I tried to concentrate on the sculptures, in that impersonal and objective way that one imagines the critic ought to do, I found my notes getting inextricably jumbled up with the gossip and shop talk flowing on about me. As everyone knows that Reg Butler’s stature among postwar British sculptors, is, by now, almost as secure as that of Henry Moore himself, I hope I will be forgiven for the generally carping nature of what follows.

The atmosphere was relaxed, and far from that almost religious hush which seems so often to descend upon the better galleries of London

Too, I remember that some years ago I was refused permission by Mr. Butler to photograph some of his sculptures. I believe that the purpose behind this refusal was that he wanted the photographs by which his sculptures would become known to the public to be interpretations representing only his own aesthetic attitudes. The trouble is that his own photographs are often not only undistinguished but poor. I refer the sceptical reader to the catalogue.

I have only admiration for the fact that every sculpture is illustrated; but these photographs raise a further problem that is more properly sculptural. This is, that Butler imposes upon his bronzes a blackish patination. While I was in the gallery, he was occupied in giving a last minute polish to some of the figures, with what I took to be an ordinary shoe brush. I could hardly help recalling those famous Gandhara sculptures, now in the Peshawar Museum, which owe their preservation to the officers of the Guides at Mardan. Unfortunately, they also took the trouble to try brightening up their collection by an occasional blacking and polishing. The result was completely to obscure the surface texture and finish, and, of course, to make it almost impossible to secure satisfactory photographs.

I don’t in the least claim that any such extreme result follows upon Butler’s treatment of his figures – all beautiful young ladies, by the way – but I do suggest that it is something worth thinking about. Even apart from photographic difficulties, the tendency, if one is to make out much of anything at all, is for the highlights to accentuate themselves as more and more light is required. The effectiveness of the surface textures also tends to diminish. I find it odd that Butler should desire this, particularly as I know that he greatly values the foundry marks on Study for Circus II, for example, which was specially removed from the attentions of the staff of Susse Freres, in Paris, before their usual “smoothing” processes could be undertaken. I am sure that Butler is right in thinking that these hairline mould joints give an immediate sense of vitality to the figure – a vitality perhaps otherwise somewhat reduced by the mere fact of turning over the casting to craftsmen, however skilled, in place of the artist himself.

Every bronze in the present exhibition has “an edition of eight casts numbered and signed”. I wonder why exactly eight for each and every one? Apart from the phenomenal cost of casting, the problems involved are not dissimilar to those relating to prints. Does it really matter, aesthetically, that a work of art is not unique? And if the edition is done by craftsmen, is it properly an “original” ? Sir Kenneth Clark recently gave a masterly lecture at Oxford on the work of Rodin. There was no doubt in his mind that the intervention of other hands on so much of Rodin’s output – practically all of his marbles, often carved by Italian craftsmen from bronze models, and horrifying percentage of his bronzes sometimes even made from the marbles – aesthetically disastrous. The sceptical reader is referred to Le Penseur in the Tate.

Does it really matter, aesthetically, that a work of art is not unique?

Like most of Rodin’s works, Butler’s are very “ideal” figures. Not only are the forms fundamentally firm and youthful – there is none of the realism associated with mottled flacidity – but there is little essential concern with either impressionist or expressionist values. I take this to be so, despite the appeal these figures must make on all those committed to the investment values of the ‘modern masters’. What the modulations of Butler’s surfaces really do is to counteract the effect of his blackened patination and to catch and focus the eye upon a given, limited, surface area of form – as light itself is caught and ‘focused’. The result is that one is made aware (a) of the modelling (casting) as such (as one is aware of the paint of the abstract expressionists), and (b) of the shape of a given section, not as the outlined delineation of an all-over form, the whole form, but as a particular bit of shape in front of one here and now. In the midst of faintly decorative overtones of decay, there is a kind of salvation in fixating upon a tiny detail. It is as though the sculptor himself were saying: “I know none of us can possess the all-over magnificence of my drawn girls; but in even the most ordinary of women there are always areas, segments, sections, bits of genuine beauty, if only you will look and concentrate upon them. Indeed it only by such obsessiveness, such neurotic intensity, that the spirit of man can rise above the smooth forms of that ideal “dream mistress” that none of us ever has for long. She would, in any case, prove an empty vessel just because her very perfections would let the eye, as well as the hand slip from area to area without focus or grasp.’

Which brings me back to my carping: Butler’s drawings are undoubtedly attractive and effective but they are too polished to be working notes. Is Butler a sculptor, or is he producing crafted decorations? From a lesser artist, their evident appeal would deserve much praise; from Butler they are suspiciously in the unenviable postwar tradition of that master of soul-selling, Bernard Buffet.

I have been shocked – I use the word deliberately – to visit three exhibitions in the past week, each of which has sold out. Dubuffet, Hitchens, Piper; these are all ‘big names’, and I have no way of knowing whether their works have been purchased as speculative investments or not. But now the same situation is promised for Butler’s show. It is just not true that all the works of all these ‘names’ deserve such success. In Butler’s case, these new works seem to me, on the whole, to be without great new invention. They are, rather, extremely capable craft works turned out for sale. We all know that artists, with an exhibition in the offing, decide to turn out ‘half-a-dozen small ones’ to round out the sales possibilities. This is not exactly immoral, but it is not creative art at its highest pitch, either. With all knowledge of how little my own view matters, I suspect that Butler’s very success is facing him with one of the crucial struggles of his life – if his artistic personality is not to repeat Picasso’s sad phrase : “Copier les autres c’est necessaire, mais se copier soi-meme, quelle pitie”.

First published in Art News and Review, 18 June, 1960