Monday 22 June was Windrush Day, commemorating the arrival, on the same day in 1948, of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury docks in Essex, UK. Onboard were 492 passengers from the Caribbean – among the first large-scale emigrations from Britain’s then-colonies, of men and women coming to work in the reconstruction period of the postwar years. With all colonial ‘subjects’ gaining the right to citizenship with the passing of the British Nationality Act of July 1948, the Windrush arrivals signaled Britain’s shift from a largely white, Christian country to the multi-ethnic and multicultural country it is now.

And by the 1960s, artists from the Commonwealth were living in and working in Britain. Here, ArtReview here goes back to 1961, to the pages of its predecessor, The Arts Review, to revisit a review by G.M. Butcher (a regular contributor and The Guardian’s art critic) of an exhibition of work by South Asian artists at the Bear Lane Gallery in Oxford. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had announced that the country would apply to join the European Economic Community,( the precursor to today’s European Union). Speaking in the House of Commons, Macmillan had promised that the United Kingdom would not enter the Common Market without assurances that its ‘obligations’ to the Commonwealth would not be compromised.

Butcher takes this as starting point for a piece that extols the cultural exchange made possible by free movement across national borders. London’s (recently acquired) status as one of the ‘metropolitan magnets in the world of art’ was made possible because it was a ‘home away from home’ for those who believe that it might be possible to belong in two places at the same time, without having to declare allegiance to one at the expense of the other. And 60 years later, with immigration and race still live political issues, yet when migration means people of different cultural backgrounds are no longer from ‘elsewhere’, the issue that Butcher identifies as facing these South Asian artists – of how cosmopolitanism and differing cultural traditions might work together, or, to put it even more simply, how to be different and together – is a question British society has yet to resolve…

Whatever effects the Common Market may have upon short-range Commonwealth economic relations, the Commonwealth idea, as an intercultural concept, has a tremendous future before it. There is needed only the will, and a relatively modest financial commitment.

In at least one limited field, that of painters and sculptors from Ceylon, India and Pakistan, the reality of the Commonwealth link has been increasing year by year over the past decade. There are now more than 20 artists from South Asia living and working in the London area. They have received singularly little official support; but they have chosen to come here, despite the rival attractions of Paris, because London is, for them, the obvious ‘home away from home’. Of course, there are neither the language nor the employment difficulties associated with living in France; and it is a fortunate chance that London has become, along with New York and Paris, one of the three ‘metropolitan magnets’ in the world of art.

To draw a parallel, there are certain similarities between the situation of South Asian artists now in London, and that of American painters before and during the war. Just as the Americans migrated to Paris in the ’20s and ’30s, so, many of the younger South Asians are choosing London – or Paris – in the ’50s and ’60s. No one can foresee how quickly this interchange will produce generally important results. One hopes there will be no occasion for European artists to become refugees in South Asia – as they did so significantly, in America during the last war. On the other hand, the pace of development, in so many activities, seems to accelerate day by day.

It must not be thought, however, that the presence of South Asian artists in London implies the loss of their national characters. Post-war New York painting looks very little like pre-war French painting. In the same way, even though the South Asians are still at work in our midst, the best of their paintings and sculptures look quite unlike their British counterparts. Altheugh there is a great deal of technical and theoretical influence, it is, in most instances, undergoing a profound adaptation to the various strands of South Asian sensibility.

It is as a convenient ‘progress report’ that the Bear Lane Gallery, of Oxford, has conceived its November exhibition. 21 artists are included, in order to give a certain breadth, and also to indicate the volume of activity taking place. But there is no intention of implying the existence of any ‘school’. Each artist is working as an individual; and many are quite unknown to each other. It is also, of course, the intention to mount as good an exhibition as possible. This might, in principle, have been better achieved had the number of exhibitors been limited – but at the cost of a considerable portion of the exhibition’s ‘situational’ interest.

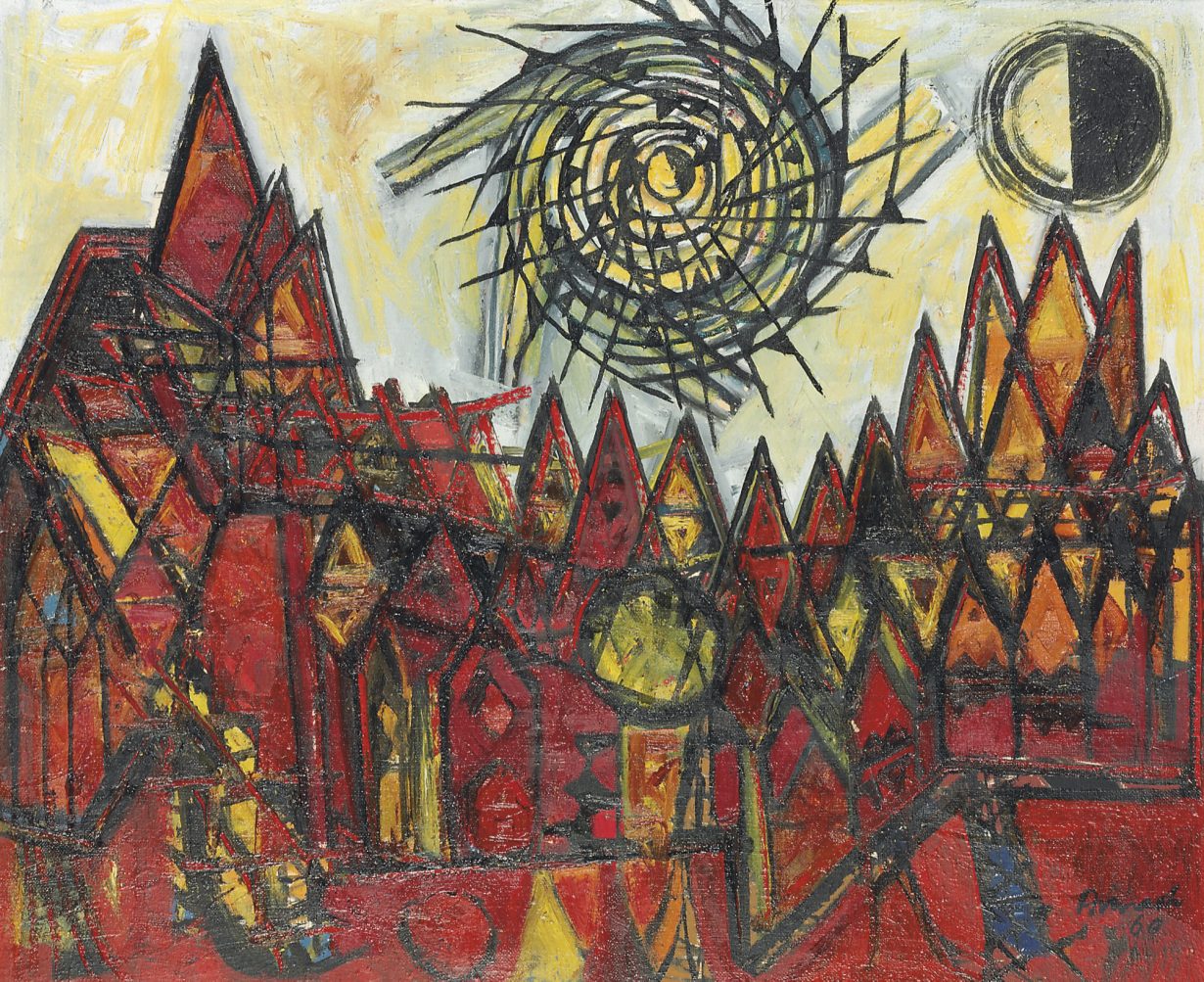

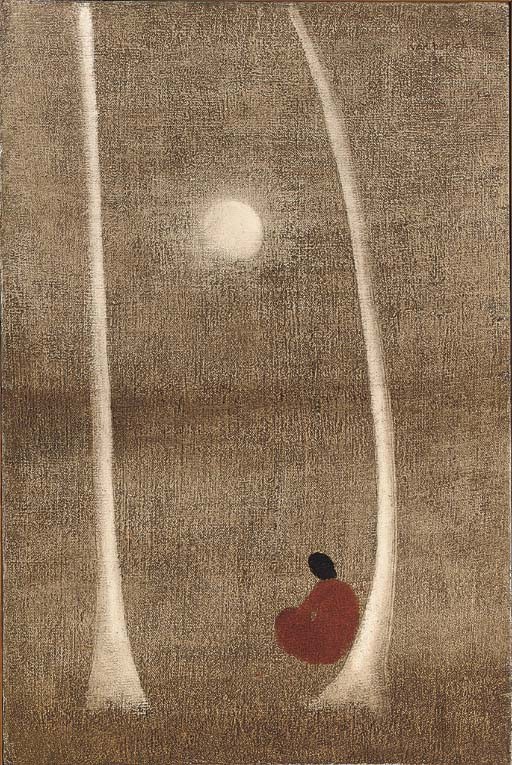

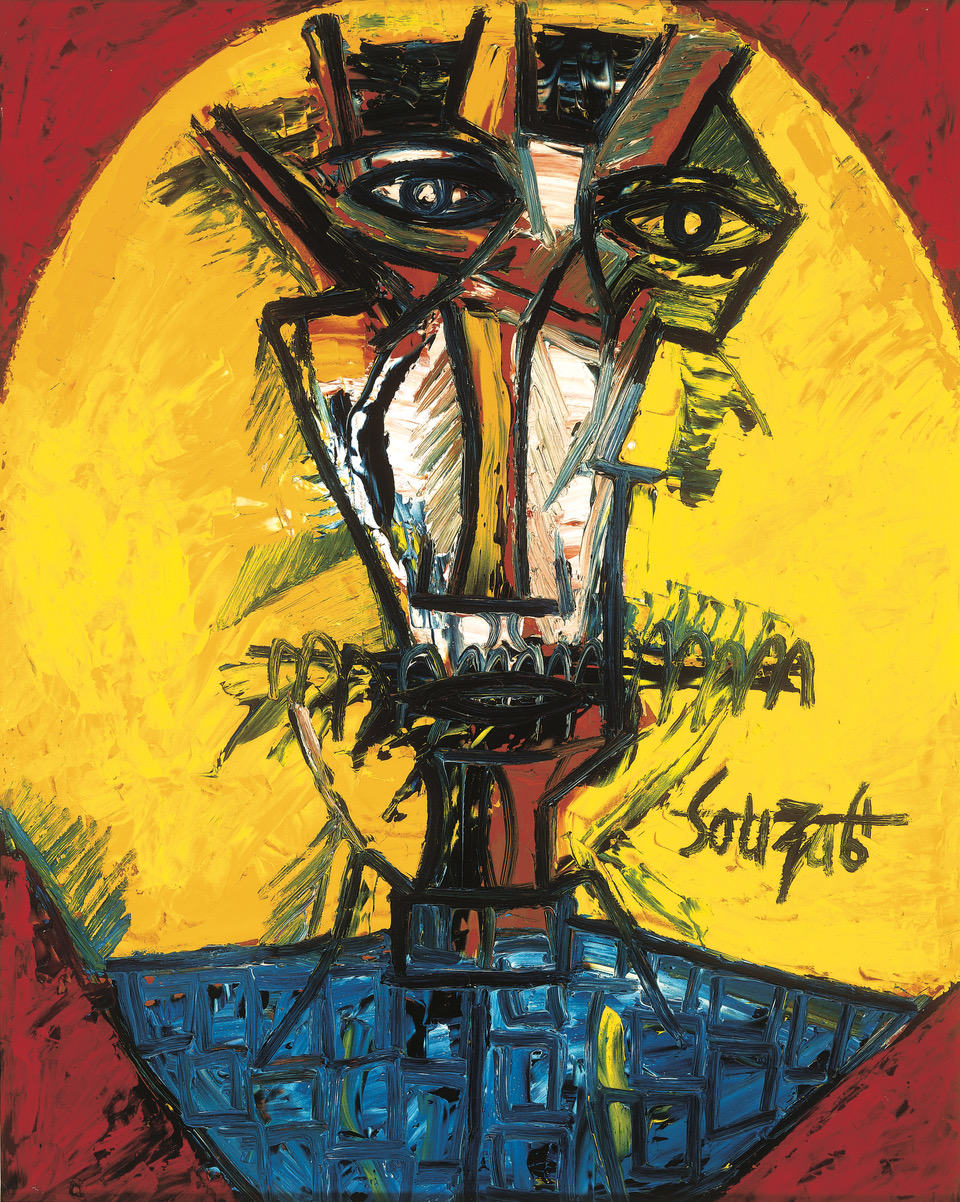

Some of the artists included are already well established, like Avinash Chandra and F. N. Souza. Others are first-rate artists who, for one reason or another, have not yet made their mark upon the London scene. Perhaps the two best examples of this are Tyeb Mehta, from India, and Ivan Peries, from Ceylon. At the other extreme of status are those who are just emerging from their student years. This is not reflected as closely by age as one might think; for most are obliged to earn their livings in fields other than art.

As for the paintings and sculptures themselves – and I write before the exhibition has been hung – there are certainly a few things of very high quality. Price alone, however, is not a direct criterion of value. Souza’s Crucifixion at 570 guineas is the expensive picture in the show, as well as being the most compelling work; but good things can also be had at prices from five to twelve guineas. Yet, however interesting the price opportunities for collectors may be, there is the added incentive of the Commonwealth idea. Just as the provinces tend to look kindly on the work of local artists, and Bond Street, on the work of British artists, so might the time have come for the public to particularly encourage Commonwealth artists. This is a ‘provincial’ and extra-artistic appeal, I know, but it is at least a wider provincialism.

And yet, is it just a matter of provincialism? For the whole point is that the encounter between the artistic traditions of South Asia – as personified in these 21 human sensibilities – and the contemporary standards of artistic achievement in Europe, is on the edge of producing a great movement of painting and sculpture which will enrich us all. The imminence of this achievement would naturally have been more apparent if it had been possible to choose South Asian artists from New York and Paris, and from Ceylon, India and Pakistan as well. Let us hope this may one day be possible. But it is worth noting that the Bear Lane’s exhibition is, so far as I can discover, the first of its kind ever to have been held anywhere.

It can be objected that there is very little in common between, say, Ceylon and Pakistan. This might be true were it not for their common share in the traditions of Greater India. For example, Ranil Deraniyagala, from Ceylon, is at this moment painting a figure subject with a reproduction of one of the wall paintings from Ajanta propped up beside him. And M. J. Iqbal Geoffrey, from Pakistan, has just completed a picture in which the symbolism has been interpreted in the emotional manner of Indian miniature painting. I should like to go on with example after example of certain common traits underlying the surface of apparently very disparate works; but as this is not possible, I can only suggest that the visitor take careful note of the colour harmonies of these painters, of their propensity for flat patterns and black outlines, and of their resistance to the loss of the human image. For in this exhibition, one may reflect for himself upon some of the problems facing the artist who tries to be both modern, and a projection of the traditions of his homeland.

First published in The Arts Review, 4-18 November, 1961