Singaporean artist Ho Rui An’s ‘performance-lectures’ consider the pervasiveness of neoliberal logic – a logic that ‘has infiltrated all manner of life, including politics, film, art and most chillingly, individual subjectivity’

Dressed in a crew-neck jumper and slacks, Ho Rui An is on stage, telling us how during the late 1970s, when China was undergoing historic socioeconomic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, Chinese delegates came to Singapore to get pointers from Lee Kuan Yew’s government on how to modernise their country. Photos of said delegations flash on screen behind him. The officials are sitting around large, mostly empty conference tables. Ho says that the tables’ emptiness evokes “an overwhelming sense of lack”, which he associates with another void: the absence of real people (as opposed to the ideal of “rational, self-possessed individuals”) in the Chinese Communist Party’s dream of a socialist market-economy. Ho then begins a series of riffs linked by metaphor or image, flitting between modes of control deployed by the Singapore and Chinese governments. For example, a look at cinematic tropes centred around the factory eventually leads to a discussion of the genre he cheekily calls “Workers Never Leaving the Chinese Socialist Factory”, because the factory had expanded to colonise private and mental life. The lecture ends with a wistful look at the older, revolutionary-themed artworks in the National Gallery Singapore – traces of a tradition of resistance, before Singaporeans had assimilated, lemming-like, into the state’s brand of benign authoritarianism.

This is Singaporean artist-writer Ho’s latest lecture-performance, The Economy Enters The People (2021–22). After the live event, viewers can watch the recorded version on computer screens arranged on a conference table similar to the ones he has just described. This piece advances a recurring motif in his work: how neoliberal logic – the economic creed that prizes free trade and the free movement of capital, goods and people – has infiltrated all manner of life, including politics, film, art and most chillingly, individual subjectivity. Beyond a set of economic policies, neoliberalism has come to be regarded, in its most radical sense, as both the fundamental reframing of subjectivity as human capital. And Ho’s conclusion is pessimistic: the expansion of the market did not deliver its promises of individual empowerment and freedom, but introduced new and more insidious methods of political control.

Ho’s body of works span performance, video installations and books. In his earlier works, he focused his critique on Singapore. Because the city-state is known for hyper-efficient governance and its business-friendly image as a ‘green’ or ‘smart’ city (in its drive to attract transnational capital), Singapore was an ideal example from which to critique the self-replicating methods and technologies of a globalised neoliberal state. The lecture and video installation Dash (2016–18), which begins with an infamous dashcam-footage clip of a road accident in Singapore, argues that the way we interpret an event as an accident – or an aberration in a fundamentally sound system – and move on from it can make us complicit with that system. He then explores how the Singapore government adapts to the crises of capitalism without challenging its logic. A prime example of this is the state’s use of ‘horizon scanning’ – a form of foresight planning that detects potential future threats – to obscure the more banal and current crises of inequality and exploitation of migrant labour that underpin its economy.

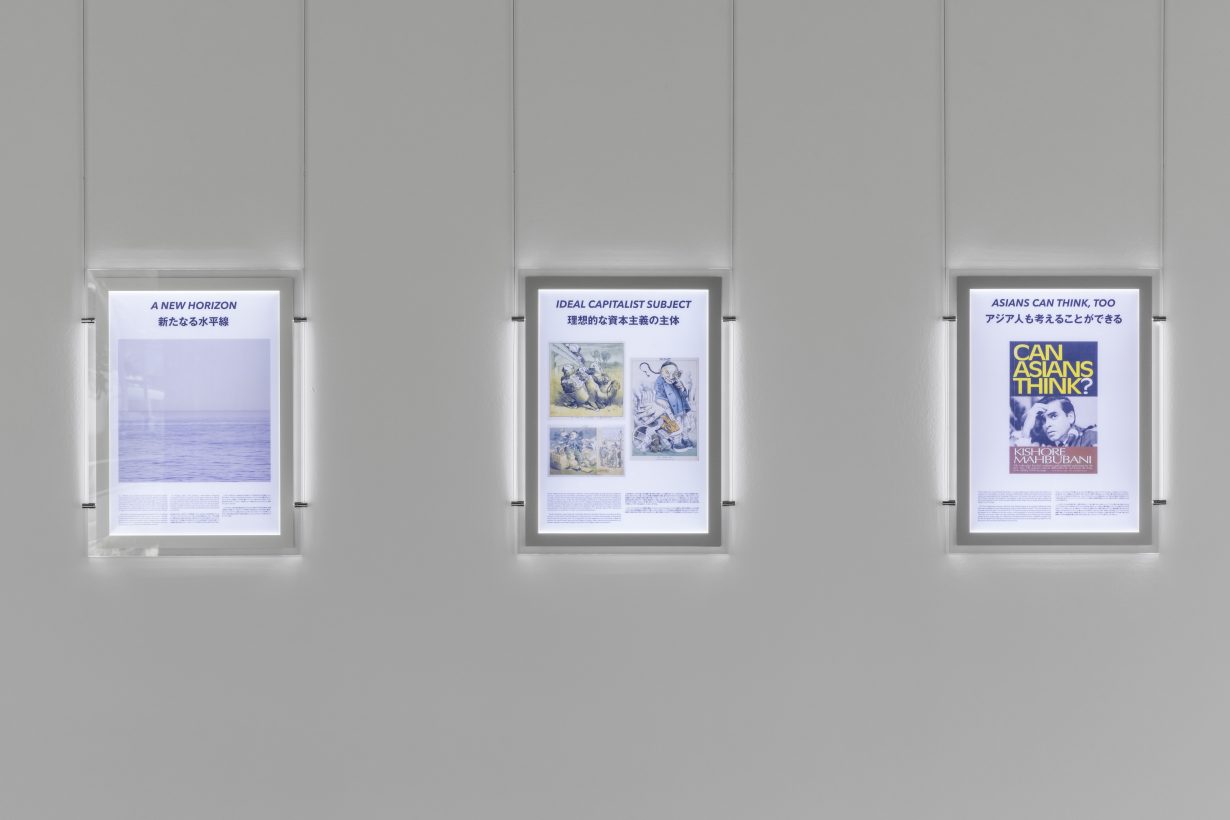

Over the past few years, Ho has looked at Asia more broadly, especially in relation to the racialised narratives surrounding the region’s position in global capitalism. Ho argues that Asia has been the canvas onto which the West projects its prejudices – and examines how certain Asian cities or communities have been cast, depending on the occasion, as market-spoiling, cheap labour or embodiments of a debased, cronyistic capitalism. In the lecture-performance Asia the Unmiraculous (2018–20), he traces the rise, crash and regrowth of Asia’s economies, from the postwar period to the 1997 financial crisis, to current times – and the West’s complicity and hypocrisy with regards to Asia’s economic woes. By marshalling images from influential Western media including Time magazine covers and Hollywood thrillers set in Asian cities, Ho also gives a potted account of the genealogies of Orientalist notions in economic and political discourse – including Marx’s problematic phrase ‘Asiatic mode of production’, which was used to describe a feudal mode of social organisation incapable of achieving class consciousness, and the Cold Warrior political scientist Chalmers Johnson’s patronising description of Japan as the ‘star capitalist student of the West’.

‘Intellectual’ and ‘cerebral’ are words often used to describe Ho’s work, but judging his work against the standards of formal scholarship would be too frustrating. The arguments are unruly, with register shifts and non-sequiturs. From Dash: “Faced with the absolute unknowability of the future, the task for the analyst is to come up with metaphors for that which has no metaphor, such that one can only turn to the animals. For only with the animal metaphor can one pastoralise the monsters. Only by animal can one contain the animus of a world that has truly gone wild.”

Ho says that his lectures are meant to be evocative and not watertight. Over an email conversation, he concedes that his arguments “draw upon different modes of observation in a manner that does not adhere to the standards of empiricism as defined from any one discipline”. This method allows him to bring speculative propositions into areas like geopolitics or macroeconomics, which are usually dominated by economists and policymakers, who make “broad, sprawling arguments about ‘the global economy’ or ‘the liberal international order’, which, unsurprisingly, tend not to espouse the most progressive politics”.

From this angle, Ho’s art is often framed as a form of knowledge production – and rightly so, especially compared to a lot of contemporary art which has an ‘aura’ of critique without much actual wrangling with the issues they purport to challenge. The unusual entry points he creates to tackle familiar topics also yield new perspectives and conceptual frameworks. The lecture performance Screen Green (2015–16), for example, was inspired by a screen capture of Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at his National Day Rally speech in 2014, where he was pictured against a homogenous green backdrop that was incidentally of the shade used in special-effects compositing. The lecture is ultimately about Singapore’s state censorship, propaganda and oppression of civil liberties, but Ho skins the cat differently: he examines how the manicured gardens of Singapore function as green-screen studios for the government to project desirable images of the country, and also as spaces of exception where civil society is allowed.

Yet sometimes I’m not so much convinced by his arguments as impressed by how cleverly and intricately they are stitched together. What is more compelling about his work, I would argue, is the powerful image or idea he harnesses to make his case. The atmosphere of capitalism is naturalised to a degree that it is lived by us all, but remains largely unlocatable, being everywhere and nowhere. Mark Fisher famously called it ‘capitalist realism’. These images that Ho selects – even if they don’t quite pierce the veil – provide an important descriptive truth of it.

One of the most arresting scenes in Asia the Unmiraculous shows a two-euro coin balancing on the window sill of a Chinese high-speed train, which was uploaded by a YouTuber to show how stable these locomotives are. Ho isolated the clip, looped it and hived it off into a standalone work called ULTIMATE COIN TEST CHINA HIGH-SPEED RAIL (2018). What the video reveals is that the kind of movement capitalism aspires to – a smooth, unfettered circulation of finance, goods, labour and ideas – is actually a kind of stasis. It is speed sped up to the point of stillness. This work captures it perfectly: the tranquillity on bullet trains, bolstered by the lack of anchoring scenery outside the window – just an anonymous brown-and-green landscape streaking and warping endlessly and impersonally. Meanwhile, the serene equipoise of the two-euro coin makes for a complacent, quasi-malevolent presence. (I couldn’t quite put my finger on why: could it be the ‘2’ on the coin signalling some vague division from the whole, visually reinforced by the solid black line of the window’s rubber seal running behind it?) Embodying creepy and contradictory forces of motion and paralysis, the work distils the ambiance of capitalism.

In our interview, Ho is explicit in his belief in the revolutionary potential of art. He says that art should try to get a foot into the discursive spaces of economists and policymakers to “articulate a progressive vision for an emancipatory mass politics”, which “can only happen when we start to see each of our local struggles as part of a more general struggle for equality across the world”.

What is this vision, exactly? It has to do with our sweat. Ho comes close to a cautiously worded manifesto at the end of Solar: A Meltdown (2014–17), which traces imperial legacies in the avoidance of perspiration from colonial times to our globalised present. The lecture starts with the idea of the sweat-drenched colonial master in the tropics and his accessory, a white wife or governess who kept a cool house in which he could rest. Starting off with footage from The King And I (1956), about a British governess who teaches English to the Thai royal family, Ho sketches out his ideas of the ‘global domestic’ (comprising “a compulsive hospitality in which strangers are forced to open up, to communicate”) and the ‘solar domestic’ (where “utopia unfolds within a supercooled interior like a parallel montage of the meltdown outside”).

The lecture concludes: “After all, the only common condition that we can possibly share is not love, but sweat. What we share is the common suffering of being under the same sun we cannot master, the suffering of the primal labour of perspiration that cannot be eliminated, only redistributed. Such is the limit of love. And it is only at this limit where we would find that the only collective life worth living is one that is based not upon the sharing of a world but the sharing of the sweaty condition of being without world. Of being always already exposed to the unworld that is the Solar.”

In Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974), the anarchist physicist Shevek famously says, ‘It is our suffering that brings us together’. Sweat, like suffering, could be a basis for a new collectivism. Sweat also serves Ho’s more radical argument. He has compared the comforting, maternal, deadening safety of globalised sameness with a sort of evil, never-ending air-conditioned interior. We need to go outside, where we sweat. And sweat, as a bodily fluid leaving the skin and showing the body’s permeability to the wider environment, dissolves the boundaries between inside and outside. The new world, or ‘unworld’, as he calls it, requires not just a dismantling of categories and hierarchies, but perhaps even their complete abandonment. The revolution needs to go beyond political action to a complete perceptual rehaul, for us to be released to the non-binary wildness of immensurable magnitude (‘the solar’), where our senses are scrambled, disordered and completely overwhelmed. How to get there? Well, there’s talking about sweat, and then there’s really sweating, with all of its inelegance and even helplessness. Yet Ho’s ultimate strength, for which he is roundly and justly celebrated, is in keeping his cool, even while navigating the most inhospitable of terrains.