J.J. Charlesworth finds that as art goes virtual it only increases the value of the real

As coronavirus lockdowns have been imposed in countries across the world, galleries and museums have been forced to close their doors. Art – in the sense of it being a thing still mostly made by physical human beings and shown in physical spaces – has disappeared. Understandably, as physical venues go dark, curators, institutions and gallerists have done what they can to move their presence, their artists and their programmes online: commercial galleries have rushed to set up online viewing rooms; museums and public galleries have mobilised their media teams to produce more documentaries and show walkrounds. But, inevitably, many venues – faced with evaporated revenue streams and staff furloughs or redundancies – have shifted to offering content that requires only minimal reference to their physical presence: texts to read, videos to watch, podcasts to listen to. And, in that sense, they are twice disappeared.

Everyone means well by keeping us entertained, interested, in touch, while we sit inside. Art magazines like this one are no different, doing the best with a bad situation. But as we remain in our lockdown reading this or another article, or watching another video, it should also be said that this is not enough. I want the old world back, and as soon as possible, and this is no way to live. Because although we’ve become intensely aware, over the last decade, of the encroaching presence of the digital network and its effects on our culture and our society, we were always able to compare the virtual world to real life. And, in most cases, to be clear about which was which.

For sure, we still meet online and work from home. Cultural and political discussions are going on in Zoom gatherings, socials are taking place on Houseparty. Things are still getting done and many businesses are still running (just). And those artforms that already circulated digitally do so with a new intensity. But musicians and dancers no longer perform onstage, authors do not read at book festivals, DJs do not play to packed clubs, and artworks are not exhibited to viewers. Connectedness only goes so far through wires and wifi, and, unless we’re deluding ourselves or being simply dishonest, we should realise now how much real, physical, urban, material life – the world in which artworks live – means to us. Because, for now, while IRL has been suspended, we’re suddenly aware of what we most value about real life: meeting people by chance in the street, sharing a drink with friends in the open air; gathering to celebrate (or to mourn), gathering to speak, discuss, argue; gathering to protest; gathering to watch, listen, move, dance. Gathering freely, to make new associations, to make new things out of material life. Gathering to make life happen. It turns out that a wholly virtual culture (and wholly virtual art) doesn’t mean very much without a real material life in which to interact.

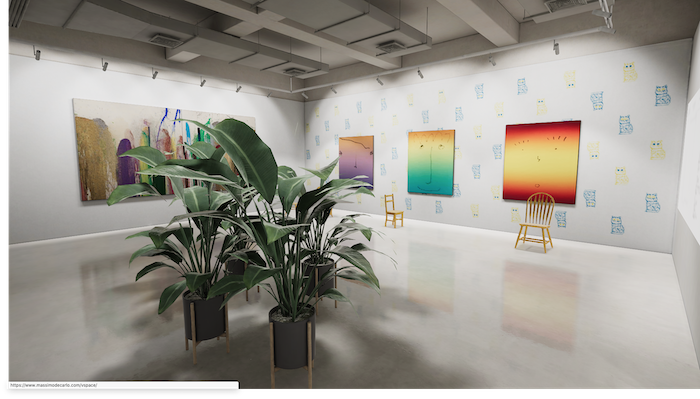

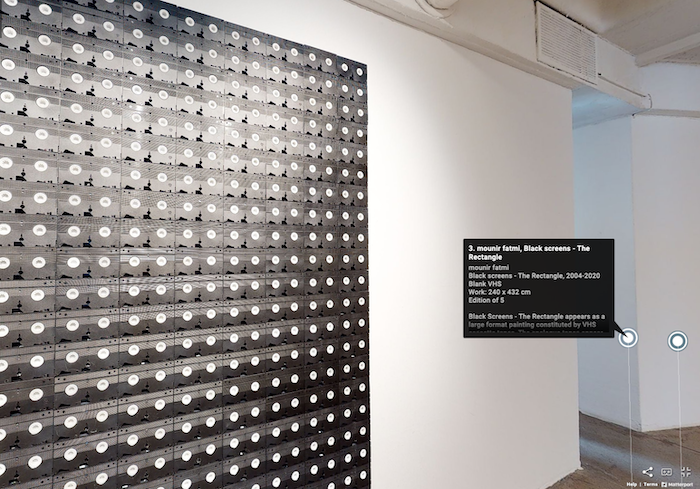

Perhaps this is why, among all the initiatives to keep art alive during lockdown, it’s worth paying a little more attention to VR gallery shows. Virtual reality (and its sibling Augmented Reality) has always seemed like a bit of a gimmick, or too nerdy, and anyway always a few years away from being perfected. But like other telepresence technologies that have been seized upon by galleries and institutions as COVID-19 survival techniques, the VR gallery exhibition has had sudden boost. To show that the doors are still open in one reality, even while they are closed on another. The VR gallery show, enabled by technology platforms such as Matterport, Eazel, Google Streetview and others, started out as a hopeful spinoff for gallery self-promotion in an increasingly crowded yet disparate international market. But unlike the more prosaic ‘virtual viewing rooms’ into which big hitters like Gagosian had made early forays (and which Art Basel hurriedly put into place to compensate for the cancellation of Art Basel Hong Kong this year), the VR Gallery platforms remind us that artworks aren’t just abstracted entities floating in a virtual sales catalogue (something virtual viewing rooms reek of). VR exhibitions remind us that artworks come to life in the space of public presentation, whether it’s that of the commercial gallery (for example in Massimo De Carlo’s just-launched virtual exhibition by John Armleder and Rob Pruitt) or the regional art centre (such as Johanna Unzueta’s exhibition Tools for Life at Modern Art Oxford), or the large international exhibition (such as the Sāo Paulo Biennial’s Google Streetview of its 2016 edition).

These are admittedly strange experiences, and it’s perhaps because we sense the tension between our real confinement and our virtual freedom to roam these spaces that we don’t like to dwell too long on our encounter with these simulated spaces. There’s something melancholic in roaming these soundless interiors, records of a world that has just disappeared.

But to this art critic, the VR gallery reminds us that art only really means something when it appears in public, in the visible, physical, social world. An artwork isn’t just an isolated object floating in the cold storage of a collector’s inventory – it’s an event made by an artist, framed by dealers and curators and others, and eventually seen by a public. And, while we might find ourselves fiddling clumsily with the mouse controls or bumping into the curators’ pop-up notes (these platforms will have to improve, for sure), the VR gallery show allows us to sidestep the mediation of PR agencies, the publicity departments of big institutions, the influence of powerful curators (and yes, even the recommendations of critics). Rather than take their word that something is good without seeing it for oneself, we can drop straight into a building thousands of miles away; whether it’s a smaller gallery hosting weirdly intricate, playfully neurotic shows such as Freight+Volume’s Pungent Dystopia in New York, or a ‘blue-chip’ gallery show such as Goodman Gallery’s sombre reflection on the politics of visibility and invisibility, How to Disappear, at its space in Johannesburg.

Rather than the frictionless proximity of another webpage viewing room, or an artist’s Vimeo channel, or even an art-magazine article, all of which we view while stuck inside – apprehensive, bored, worried, angry – the VR gallery show reminds us that public space is precious, our freedom to be in it not to be taken for granted. The art venue may be a contradicted intersection of commercialism and exclusivity, but it’s also one of the many spaces to gather that we’ve just lost. There’s a strange, sad irony in the fact that in the last years, the artworld has torn itself apart over what should be shown, or who should be allowed to occupy the gallery space, or whether one group of artists is over represented or another underrepresented. Now nobody gets to show, and everyone suffers, since the public space that was once hotly contested no longer exists. If nothing else, the VR show pushes us to think imaginatively about the kinds spaces we might want to create once the lockdowns unravel, and the value of the freedom implied by being able to occupy space, gather there and do as we wish. And of allowing others the same liberty. For the next few weeks I’m looking forward to reviewing some of these shows. In the meantime, I’ve still to order my VR goggles. It’s more real in 3D, right?

Online exclusive published 17 April 2020