and Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin, Paris & London

The artist’s work is a poetic and humorous meditation on the passing of time

To see ourselves as others see us: at Galerie Max Hetzler, London, Navid Nuur gives us the gift to do precisely that with In Your Face (2007–08). We check out how we really look in a non-reversed mirror. You know it because that facial asymmetry you’ve got used to over the years is actually on the other side. Beholder beware! Maybe you’ll think the transformation makes you look better, maybe not. Nuur values such subtle metamorphoses: his work revels in alchemic change in materials, textures and appearances over time; time that works on everything.

On a white plinth at chest height we see, as if displayed in a museum of archaeology, three vases of different shapes and glazed colours. Each has a line of various small objects – shards from pots (perhaps), tiny figurines, bisected dice, a rolled-up banknote, a bottle cap – laid in front of it. The title of the work is as gnomic as these fragments: “ ”, (Archean – 2020). The information sheet gives the materials as ‘heat, time, minerals, patience, luck’. It’s a neat gag: found objects placed side by side for the viewer to compare, admire or make up stories about. The Archean Eon occurred 2.5 to 4 billion years ago, one of the earliest geological ages, and a time of great volcanic activity, when plutonic masses of granite were formed. Which item dates from back then, which from now? Nuur’s placement of these individually attractive items asks us to invent or imagine connections, mineral affinities; he’s like a Romantic poet identifying with the mutely inanimate, the inorganic. Nuur seems blithely unconcerned by any critique of the pathetic fallacy.

and Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin, Paris & London

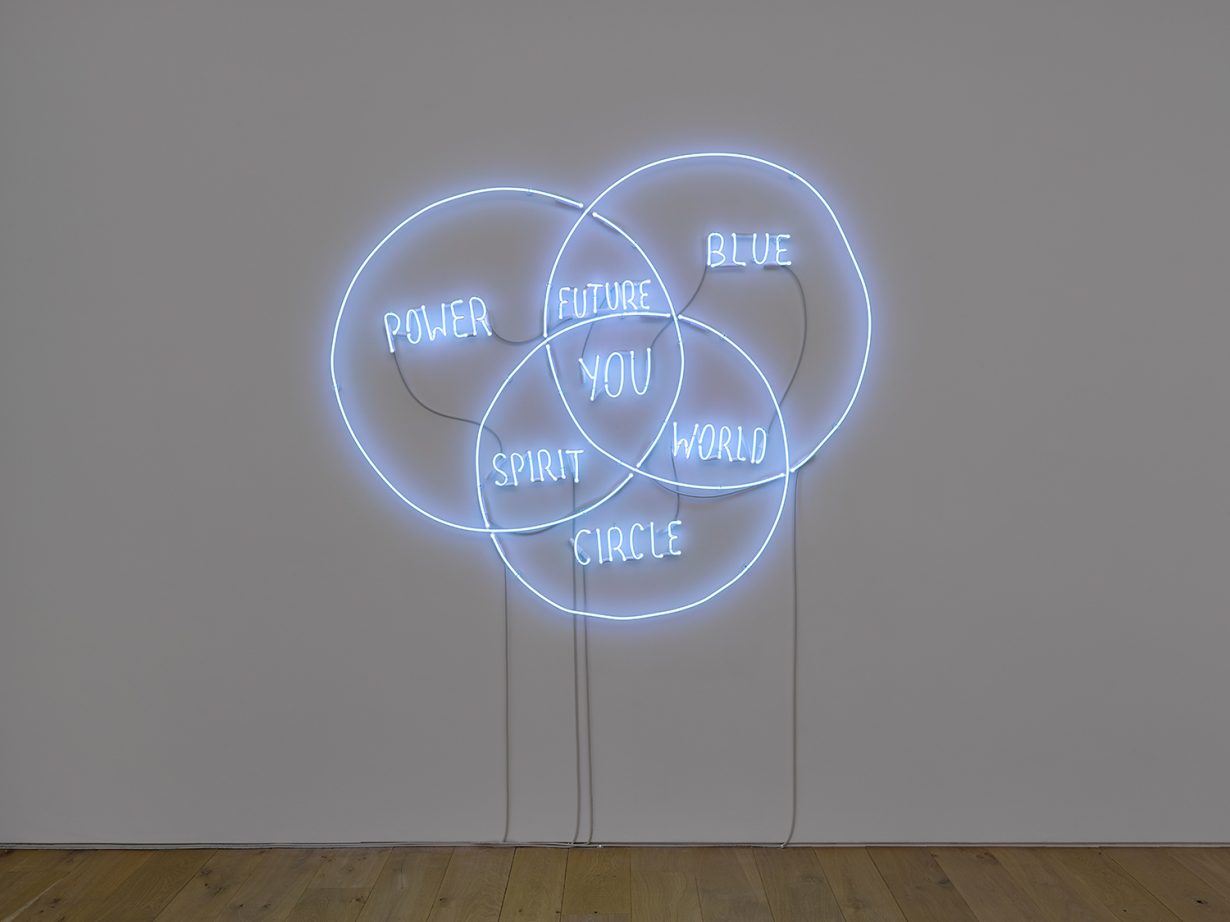

Using serpentine rock or the aforementioned granite, Hope (2012–20) is a series of small dark blocks beautifully imprinted with gold leaf. Nuur is originally from Tehran, and these exquisite pieces might point us back to the ancient Persian imagery of the lion and sun. Is that ‘hope’ an exile’s desire for a return to the sun of the motherland? His light-inspired materials can be more prosaic, as with Untitled (2010–19), in which crushed vitamin D tablets and binder are stained onto canvas. Vitamin D is synthesised in the body following the effects of light on the skin, but Nuur’s images here look neither sunny nor healthy. They are more like a textured desert landscape recalling the scraped surface of a Jules Olitski abstraction or one of Andy Warhol’s oxidation paintings. Other experiments in staining are shown with two examples from the Untitled (2004–20) series. Nuur uses home-brewed ink and ‘artist bath water’ (!) on filter paper to give us hotly coloured Helen Frankenthaler-like washes and smears that radiate a coal-fire warmth. More modern forms of light are used in the neon Mindmap (2013), a Venn diagram of blue neon and argon gas, where the words ‘power’, ‘future’, ‘spirit’ and ‘world’ intersect around a targeted ‘.\.’.

and Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin, Paris & London

Further reference to mark-making by the Abstract Expressionists occurs in The Tuners (2005–20), a giant (200 x 514 cm) linen canvas featuring a riot of anonymous doodles. Nuur has appropriated these from stationery stores he’s visited by picking up the scraps buyers have left after trying out new pens. The multicoloured squiggles variously suggest Arabic script, rivers, spring coils and waves, but also imply a secret, albeit indecipherable, universal language we all use on testing felt-tips and biros. We leave with a gift from a machine. Untitled (1976–13) is a penny press in which a steering-wheel device powers cogs that compress a coin into a new artefact, a flat shape containing the fingerprint of the artist: a neatly generous gesture to round out a generous show.

Navid Nuur: Apart from the secret that it holds, Galerie Max Hetzler, London, 12–28 April 2021