From the artist Laure Prouvost at the LAS Foundation to a new group show initiated by CERN, quantum science is following AI in its march on culture. What does this mean for today’s reality-bending times?

A century on from the birth of quantum mechanics, the United Nations has declared 2025 the ‘International Year of Quantum Science and Technology’. While the study of matter and energy at the most fundamental level (on both an atomic and subatomic scale) has been a core tenet of physics since the turn of the twentieth century, the hype surrounding the so-called ‘third revolution’ in quantum technologies has never been more intense than in recent months. Last December, Google unveiled a ‘mind boggling’ (as the press release put it) new quantum computing chip which can achieve in minutes what an ordinary supercomputer would need longer than the lifetime of the universe to solve. Named Willow, it measures just four square centimetres and, according to the company, offers substantial proof that we live in a multiverse (according to the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics), a vastly exaggerated statement that has caused outrage within the scientific community. Microsoft launched their own Majorana 1 processor last month; in development for 17 years, it supposedly fits up to a million quantum bits (qubits) and promises significant advances for quantum computing. Meanwhile, researchers at the University of Oxford this week revealed they have built a machine capable of quantum teleportation.

If you are to believe the news headlines, quantum computers will be rolled out in anywhere between five and ten years, though when I visited the International Quantum Forum – a two-day conference in January investigating the confluence of art and quantum technologies – it became clear that these such bold predictions shouldn’t be taken too seriously just yet. Though the largely cautious attitudes of scientists and engineers hasn’t hindered the exponential growth of quantum technologies on a popular and political stage. As the geopolitical arms race to build the world’s first quantum computer intensifies – China is currently leading the push, followed by the EU and US – the quantum narrative has become attached to national security through threats to encryption algorithms and the prospect of enhanced warfare. As is typically the case with any emerging technology, it can be hard to distinguish between substance and buzz.

Quantum mechanics cannot be separated from the context in which it is developed, including political and social dynamics. As such, its militaristic history is important to consider here. The Manhattan project to develop the first nuclear weapons in the 1940s worked closely with quantum scientists, while in 1972 the CIA recruited members of the quantum Fundamental Fysiks Group for a research programme at Stanford, which they jokingly called ESPionage (a double entrendre short for extrasensory perception), an experiment into remote viewing and telepathy. It can hardly be a coincidence that interest in quantum technology is ramping up at a time when geopolitical tensions are rising.

On social media, quantum-speak has already been absorbed into the currents of the online lexicon, emerging as a favourite high-vibrational buzzword among New Age spiritualists who misappropriate quantum terminology to describe anything loosely multidimensional or woo. They post psychedelic clips of ‘quantum jumping for beginners’ and shortform explainers on ‘quantum entanglement’, essentially to describe the invisible threads that connect an individual to another. Rarely are these scientifically accurate, and the technologies they would require usually don’t exist. Most of the ‘quantum’ tech that we see utilised across art and science are in fact simulations of quantum computers, not the real thing. This frames artistic responses to quantum in a speculative framework, as opposed to other emerging technologies such as AI, where discourse and development have unfolded in real-time. The question, then, is not only how artists can critically engage with topics of quantum, but why they are increasingly choosing to.

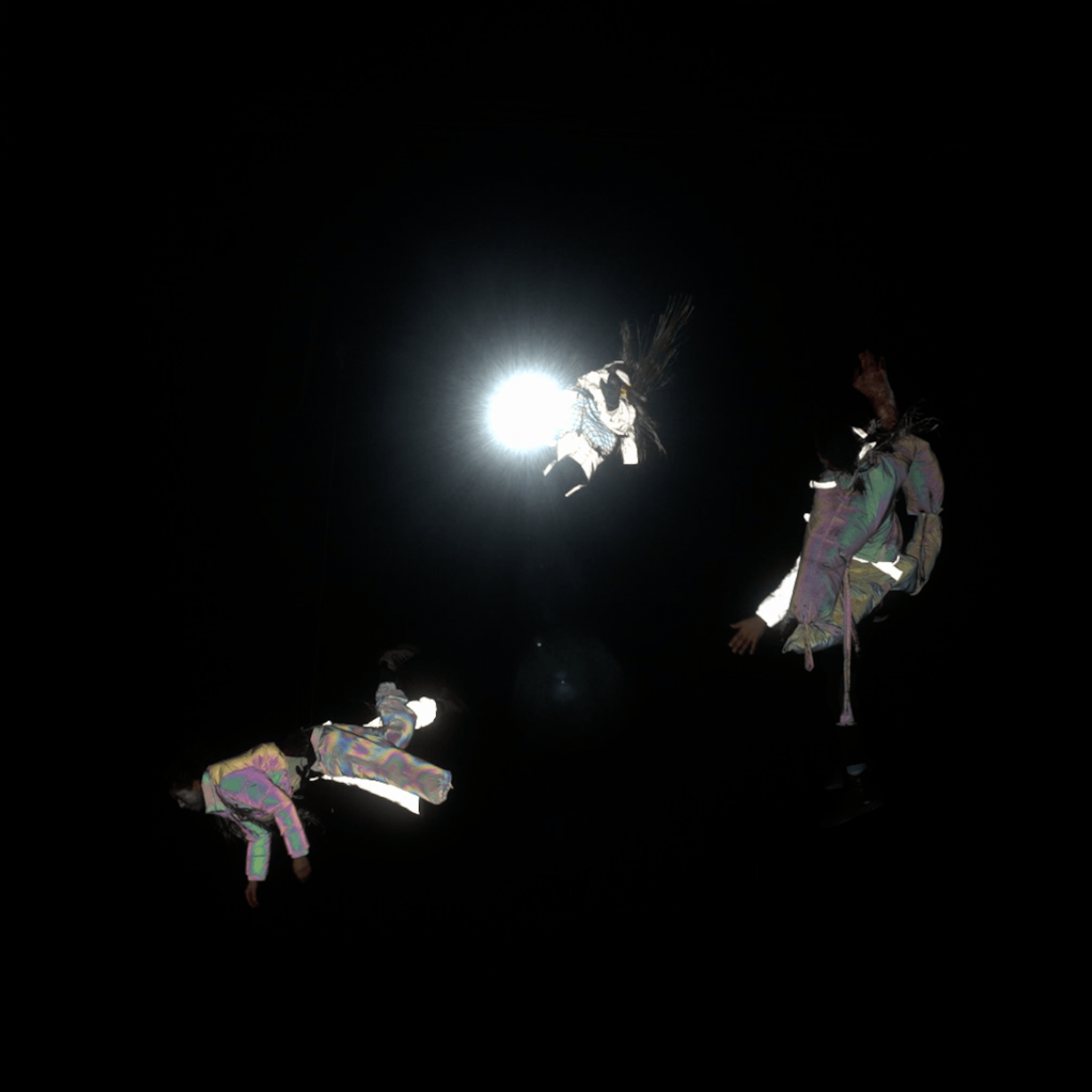

This month the LAS Art Foundation initiated their new Sensing Quantum programme with an exhibition by Laure Prouvost at a former Berlin power station, Kraftwerk Berlin. (Throughout 2026, the foundation will present further installations and a public symposium exploring quantum technologies in the arts.) Prouvost’s exhibition, titled We Felt a Star Dying, draws on the unpredictable logic of quantum physics to explore what it might feel like to sense reality from a quantum perspective. The emphasis on feeling first, as opposed to thinking, is a crucial linguistic slip to avoid describing to audiences what quantum actually is – the irony being that not even scientists know the answer, giving rise to popular memes that parody the impossibility of fully wrapping one’s head around the fundamentals of quantum physics. Instead, Prouvost uses video, sound, sculpture, scent and light to imagine what a hyperdimensional and hypersensitive view of the world might look, feel, sound and smell like. These elements react to the changes taking place around them – through heat-sensing cameras and corridors of sound that fluctuate with movement – to evoke how multiple different perspectives and timelines could exist all at once, a key characteristic of quantum physics.

Sculptures that look like meteors, made from organic moss and sticks, and inorganic wires and circuit boards, sit ready for visitors to pull over their heads like oversized helmets. Others hang suspended from the ceiling; as one rises, the other one falls, in a game of opposites intended to evoke the quantum ideas of entanglement and superposition, where a particle can exist in multiple states at the same time while reacting to one another, despite being light years apart (a phenomenon that Einstein once termed ‘spooky action at a distance’). Nearby, a video beamed from a circular screen on the ceiling fluctuates between a ‘classical’ (the version shot and edited by Prouvost) and a ‘quantum’ version (the latter is an AI interpretation of the former, which integrates random visual simulations of quantum noise, developed by Prouvost with the philosopher Tobias Reed). We see microbial patterns; moonlight; a cat; people in high-vis jackets; light rays reflecting on a body of water; these abstract clips depicting environmental noise hint at the inherent sensitivity of quantum systems and how they react to even the slightest change in planetary and cosmic forces. Instead of seeing the world as static objects with definite properties, quantum theory interprets the world as a net of relations: both human and nonhuman (animals, plants, minerals, objects).

There is an inherent playfulness to this approach that gently introduces visitors to the fundamental principles of quantum thinking without the need to explain literally. Since quantum art is still speculative, the exhibition places its emphasis on sensory experience as you move through the space, lie down on the cushioned, heat-reactive surface to watch the film, and dip your head to smell the metallic and mineral scents planted within some of the meteors. Prouvost has dubbed them ‘cute bits’ (in a tongue-in-cheek nod to qubits), to evoke the connection between celestial bodies and machines.

Exhibitions like Prouvost’s give visual form to concepts that can otherwise become tangled in abstraction, but underlying all this is the deeper question of what quantum reveals about reality itself. To exist in a quantum reality means to exist in a hyperdimensional view of the world in a constant state of flux, where many different perspectives and timelines exist simultaneously. Libby Heaney’s Ent- (non-earthly delights) (2024), a sculptural installation and augmented reality experience, brings forth Hieronymus Bosch-inspired scenes of alternative reality and medieval monsters, which she refigures as representative of quantum computing’s potential to wreak havoc on the IRL landscape. While artist duo Black Quantum Futurism (an interdisciplinary practice founded by Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillip) incorporate Afrofuturist ideas to explore the relationship between Black diasporic temporalities and quantum principles.

At odds with the modern western paradigm, these artists interrogate the transformative elements of quantum to offer alternative ways of seeing the world. It is arguably the same reason why many key scientific figures in quantum mechanics such as Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg were drawn to Eastern mysticism in the 1940s, or why books like Fritjof Capra’s Tao of Physics (1975) and David Kaiser’s How The Hippies Saved Physics (2011) are considered core reading for those trying to come to grips with the counterintuitive nature of quantum theory. For artists (or anyone) wanting to question the fundamental nature of reality, quantum physics is the bridge between intuition – grounded in the instinct that reality isn’t what it appears to be – and experiments of great precision and sophistication that are backed by hard maths.

This often-blurry line between fiction and fact is explored in greater detail in Quantum Visions, a new group show at San Sebastian’s Tabakalera as part of Arts At CERN, the creative programme of the European Laboratory for Particle Physics in Geneva. In works by artists and former CERN residents including Heaney, Alice Bucknell, Semiconductor and Yunchul Kim, the upcoming exhibition sets out to question the ‘limits of knowledge and propose new ways of understanding reality’. Each artist presents an alternative model for experiencing the world. Bucknell’s Small Void (2025), a ‘queer dating sim’ inspired by quantum entanglement, invites users to participate in a two-player ‘call and response’ game exploring the limits of language, attachment theory and cosmic annihilation. Kim’s cosmos-inspired sculptures are made of transparent polymers that constantly change colour and pattern through kinetic movement. These artworks turn away from the Newtonian model of classical physics towards an interconnected and infinite way of seeing the world that is inherently quantum.

To conceive of a quantum worldview requires us to modify the grammar of our understanding of reality – from Ancient Greek principles of existence to what the American philosopher Karen Barad refers to in Entanglements (2015) as ‘intra-action’, understanding agency as not an inherent property of an individual to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces. Such a concept of the world and our relationships is a compelling one for artists, whose work often involves seeking out the unseen political, social and economic forces drawing us together (and pulling us apart) just beneath the surface of the everyday. Yet there remains the risk that discussions around quantum in the world of art become steeped and even lost in metaphor, applying the fundamentals of physics and still-nascent technologies onto existing contemporary art discourse. After all, there still remains the human limits of our perception itself, much as artists may seek to expand it. The world might be quantum but humans still process information classically, which presents perhaps the biggest challenge for artists yet.

Günseli Yalcinkaya is a writer and researcher based in London. She is an External Research Affiliate at Moth Quantum