Marking the 35th anniversary of the original Super Mario Bros., we flick back to a 2003 feature of computer artists busy ripping up their Nintendo cartridges, profiled by Ian White (1971-2013), a performance artist, curator and regular film columnist for ArtReview. White surveys artists such as Cory Arcangel, collective Paper Rad and Alex Galloway’s Radical Software Group, who ‘strip computer consoles and their games back to the codes in which they were written, exposing, modifying and re-presenting them as profound glitches of their own systems’ – a move against the corporate gaming industry which, he argues, echoes experimental film’s own stand against commercial cinema. What do we see in these hallucinogenic, hacked games? ‘The impassioned cry of a generation into a new, lyrical resistance via the means available.’

Heralding the new is never straightforward, though always a pleasure, and there’s a new scene in New York that’s just such a conundrum. In July, London’s ICA presented ‘Radical Entertainment’: works on computer, single-channel video and interactive web-based games, curated by Lauren Cornell of Williamsburg’s most adventurous screening house, Ocularis, and the ICA’s now former New Media Curator Lina Dzuverovic-Russell.

As if to prove that the future is nothing without the past, a number of hot young artists displayed work whose disarmingly old-fashioned craft is a direct engagement with recent technological history. Cory Arcangel and his ‘programming ensemble’ Beige revel in the deliberately limited playground of early computer games; the collective Paper Rad are obsessed with Eighties graphics; while Alex Galloway’s Radical Software Group, like many of these artists, mine (and undermine) the superficially innocent territory of computing and popular entertainment.

This positioning, against the dominant culture with which these artists grew up – the gaming industry and the corporate manufacture of programs that promise liberation while disempowering users by hiding operational systems behind a glistening logo – is an echo of experimental film’s stand against commercial cinema. Arcangel, Paper Rad and Galloway strip computer consoles and their games back to the codes in which they were written, exposing, modifying and re-presenting them as profound glitches of their own systems.

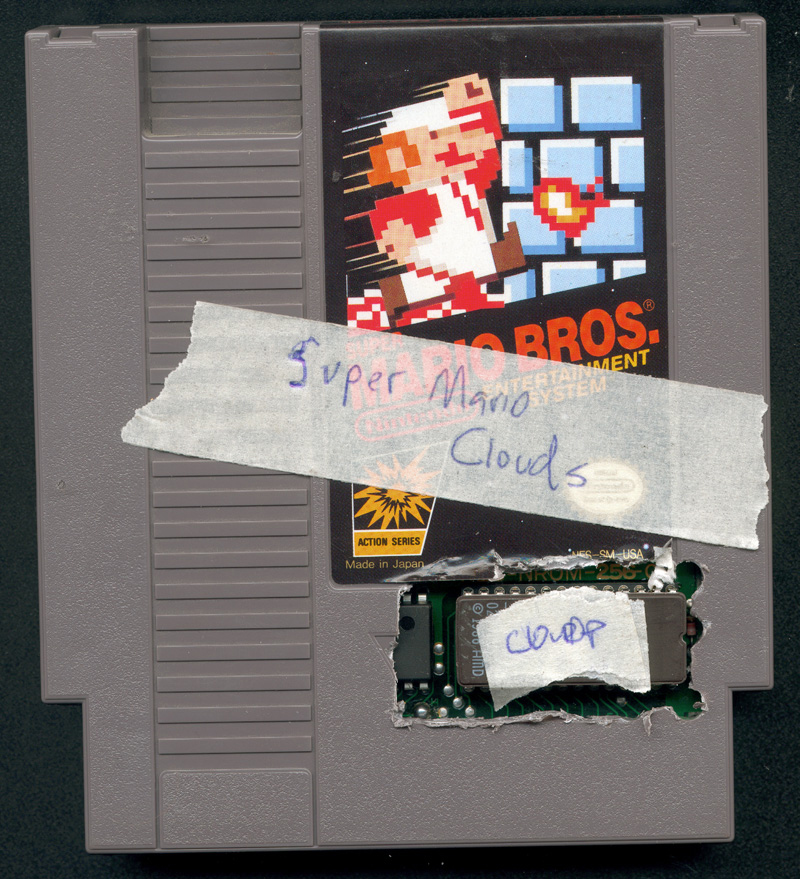

In Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds (2002) (which may be shown on a console, as installation or in the cinema), nothing is left of the original other than a sublime clear blue sky and the formulaic clouds that float across it. His own derivative game, I Shot Andy Warhol (2002), allows the user to aim for the superstar-artist while avoiding such eminences as Colonel Sanders and the Pope. Like the incredible screens of Paper Rad’s website – where multiple layers of Technicolor graphics jostle for retinal prominence, clashing and flashing against each other in celebratory, hallucinogenic montages – there is an unnerving degree of emotion in these works beyond retro-cool, more arresting than nostalgia: the impassioned cry of a generation into a new, lyrical resistance via the means available.

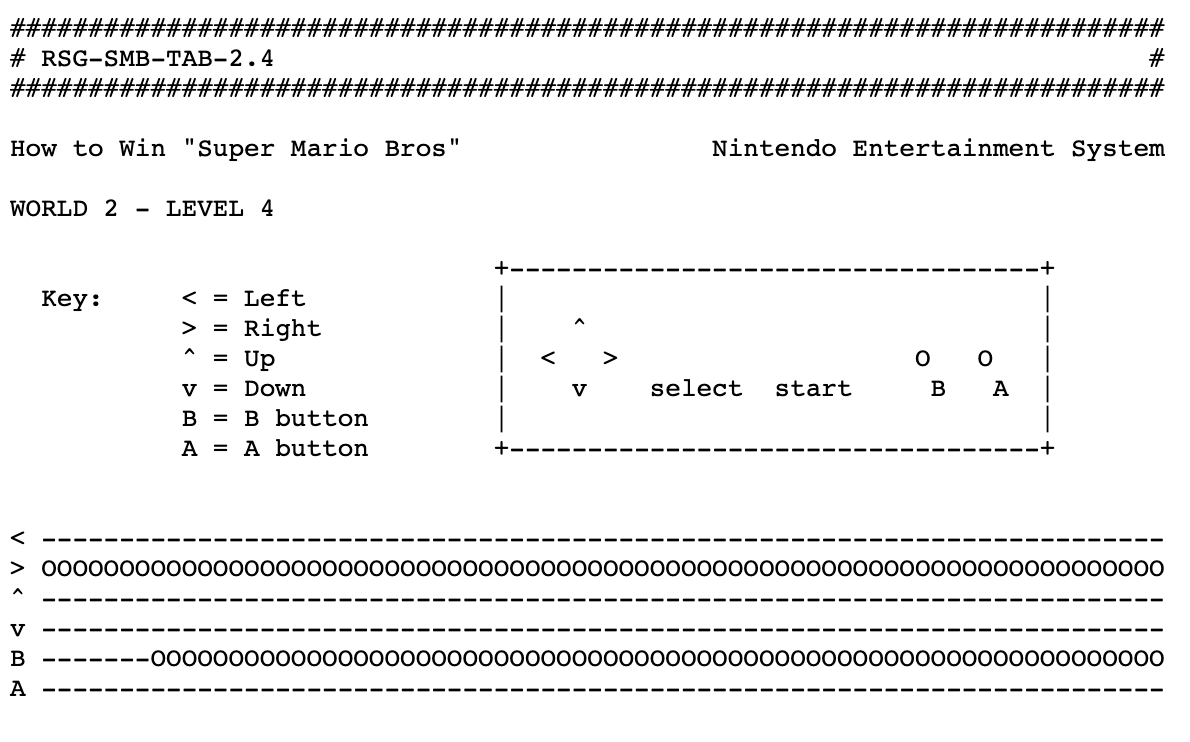

Galloway’s How to Win Super Mario Bros (2003) is a video of the artist’s hands flickering over the controls as he manoeuvres Mario through the game’s stages. It’s accompanied by a block of computer print-out, a pseudo-conceptual score in ones and zeros mapping the buttons pressed. That the viewer is literally given the key to winning, yet would find it impossible to recreate Galloway’s actions from these instructions, ultimately feels like a joke on him; a paradox that this system is as hermetically sealed as it is revealed.

In ‘Blinky’, a group show at the ascending New York gallery Foxy Productions in June, Arcangel included silkscreen prints, ‘landscape studies’ filtered through Nintendo game-code, alongside Paper Rad’s videos and prints of Arthur Cloakey’s relocated, benign cartoon character, Gumpy. Arcangel’s band the 8-Bit Construction Set extends even further, making phenomenal tracks from the primitive bleeps of old Atari and Commodore64 machines, playing gigs of which a complete inventory of the equipment used is an integral part. Paper Rad are no strangers to the rock duel themselves.

Foxy Productions are moving from their Williamsburg hotbed to the Manhattan art colony of Chelsea and open there this month, while simultaneously presenting ‘Blinky’ as a two-part screening in Tate Britain’s auditorium. The equally new-wave video anarchy of Seth Price, A Constructed World and Abbey Williams will be included among others, while Arcangel and Paper Rad will collaborate on a new narrative work for the occasion. It’s just the tip of the iceberg, and our imminent collision with it is a cause for celebration.

First published in ArtReview, September 2003