In a country where state support for the arts is almost non-existent, a thriving cultural ecosystem has sprung up against the odds

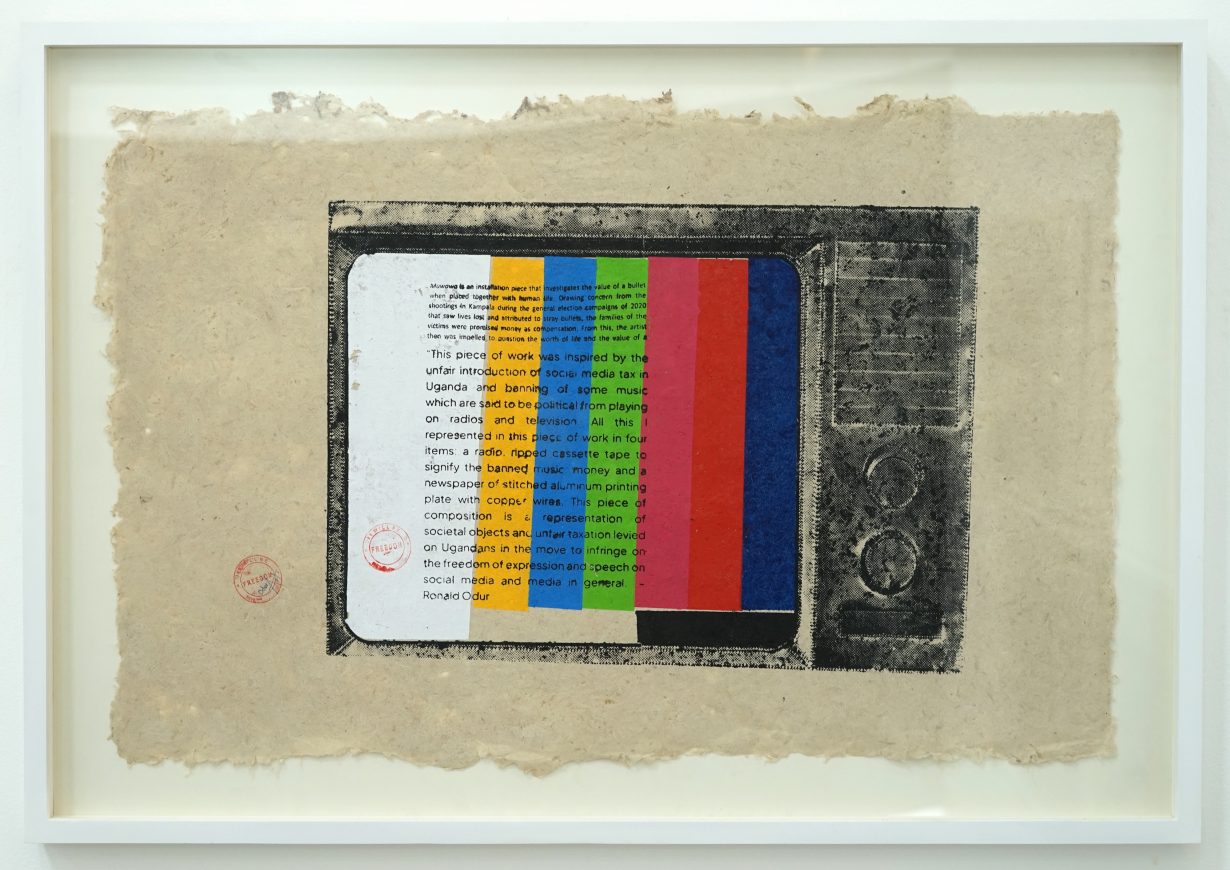

Embossed aluminium and copper wires have become the recognisable media of the work of the Ugandan visual artist, Odur Ronald. Several silver television screens, shaped out of hammered aluminium, were piled in one corner of the installation Waagawulidde? (Have You Heard It?, 2024) exhibited in a group show last year at Afriart Gallery in Kampala. Embossed bullets and overturned chairs were littered on a woven mat, representing the aftermath of the violence and death accompanying Ugandan election campaigns in 2020, according to an accompanying statement. Projected images flicker on the television screens, with phrases such as ‘No Vision’ and ‘No Signal’, and the Ugandan coat of arms on display – a nod to the state’s monitoring of media. The installation was accompanied by spoken word performances in Luganda by both Odur and the poet Ssebo Lule, and a brass band musical number. Among other pieces, the band played the Ugandan national anthem – the grandeur of which was a stark and intentional juxtaposition to the elements of violence on display. These multiple elements combined in an unexpected, contradictory and jarring manner – just like the corruption, state violence and limited freedom of expression that the piece critiques.

Odurhas made a name for himself internationally through transforming sheets of aluminium into works that comment on politics, global inequality and human movement. Based in Kampala, Odur’s work is currently part of the Liverpool Biennial. In a country with little state support for the arts, Uganda’s cultural sector is a difficult one to survive in. Odur’s journey is testimony to his resilience and ability to innovate even with little means– qualities that reflect Uganda’s wider creative community.

Odur grew up collecting and selling metallic scraps in the low-income neighbourhood of Katwe in Kampala. When Odur began making art, he was unable to afford paints and canvas, but after watching a YouTube video of someone embossing a soda can, he was inspired to do the same with aluminium plates. His works are mainly sculptural installations, consisting of aluminium parts intricately woven or stitched together with copper wire to create different objects – televisions, chairs, slippers, paint cans. Together, they form silver tableaux of scenes depicting different aspects of global injustices. The image and object of the passport is one of Odur’s most frequently produced, such as the set of silver passports dangling from the ceiling as part of his installation The Republic of This and That (2023), as part of his solo exhibition that inaugurated The Capsule Gallery in Kampala. Odur dents and burns pieces of aluminium into passport-shaped booklets, embossing them with different labels, such as ‘The Republic of Contemporary Art’ or ‘The Republic of The Undocumented’. What once earned him pocket money to buy toys has now become a means for him to process his own experiences, as well as those of the global majority.

To finance his university studies in Interior Design at Kyambogo University, Odur began painting on canvas – with paint a friend would donate to him – and selling his work at the craft market of Kampala’s National Theatre. “I was express painting,” Odur recalls. He painted quick, stereotypical images of an Africa he knew would sell to tourists, featuring animals or women with children on their backs – “NGO art,” as he would later term his earliest pieces.

Beginning and sustaining a career as an artist in Uganda is challenging: the arts receive close to no support from the government, which routinely denounces culture as a viable economic sector. This is reflected in Uganda’s education system: science teachers are paid more than their counterparts in the humanities. It is unsurprising, therefore, that there is a paucity in adequate education and training institutions for contemporary visual arts in the country. Socially, there is little prestige in working as a professional artist in Uganda, as it is associated with poverty and unproductivity – a viewpoint that cuts across all social classes. Indeed, Odur recalls his sister’s confusion at his first exhibition in 2017 – with Streetlights Uganda, a non-profit supporting art for street children – when materials and objects she had previously wanted to discard were now made into things on display for people to view.

These challenges extend beyond the visual arts to all forms of cultural production. Performances and the written word, particularly, are carefully monitored by the state. Public dramatic performances and film screenings require approval from the Uganda Communications Commission, which reads the scripts and watches the films, in addition to levying a fee per production and screening. For smaller and independent production companies, this cuts significantly into already tight budgets. Writers work in isolation with few opportunities to develop their craft, in the absence of larger culturally relevant literary circles. For all creatives, the lack of funding remains the biggest challenge, and reflects socioeconomic disparities in Uganda: only a tiny handful can afford to work as artists full-time. The state funding gap is filled by European organisational grants, such as from the British Council, the Goethe-Zentrum, the Alliance Française or the DOEN Foundation.

The increasing number of galleries, studios and arts centres around Kampala are evidence of the determined presence of artists in Uganda. 32 Degrees East, for example, holds residencies and workshops to support the work of early-career artists in Uganda. Galleries such as Afriart Gallery, Xenson Art Space and The Capsule are part of Kampala’s growing cultural ecosystem, and individual artists’ studios are dotted around the city.

Odur’s career was nurtured on the Kampala compound of 32 Degrees East. An artistic acquaintance told Odur about the arts centre, and, his interest piqued, he walked through its gates to pay the centre a visit. Through peerworkshops and training with artists at more advanced stages in their careers, from both Ugandan artists, such as filmmaker Nikissi Serumaga, and international figures, such as London-based Othello De’Souza-Hartley, Odur began to gain a greater understanding of conceptual art, and learned practical matters such as shaping proposals and writing his own artist’s statement summarising his work. The diverse community of artists at 32 Degrees East hail from Uganda, all over Africa and the continent’s diaspora across the world. They have been pivotal to Odur’s mental health and career – so much so, that he has now returned to the arts centre this year to work as an instructor-in-residence.

Many emerging artists in Uganda are self-taught, cobbling together their training through a mixture of in-person workshops and social media. It’s not perfect, but it works, in that they are developing their crafts and growing their careers. The knowledge that they are, somehow, all in this together, has enabled artists in Uganda to develop a community, and create their own opportunities and support systems. 32 Degrees East is a reflection of this: after operating out of a set of interconnected shipping containers for a decade, in 2026, it will complete construction of the first purpose-built arts building in Uganda.

International opportunities for Ugandan artists are highly sought-after, but here too, they are stifled by the whims of visa and immigration systems. Odur’s installation in Liverpool, Muly’ Ato Limu (All in One Boat, 2025) addresses this: fashioned entirely from embossed aluminium, it features dozens of chairs and jerrycans dotted on a long woven mat in the shape of a ship floor plan – a reference to Britain’s slave trade – underneath hundreds of Odur’s passport booklets suspended from the ceiling. An accompanying sound installation plays a visa office interview for an unspecified country in multiple Ugandan languages, including Luganda, Lusoga, Lunyankore, Lango, as well as in the colonial language, English. In the former heart of Britain’s slave trade, the work addresses the movement of people from the African continent to the global North. His anger with this global system of structural inequalities, in particular the humiliating nature of visa interviews, is evident. Odur is no stranger to the whims of Europe’s immigration system: while his work was featured in last year’s Venice Biennale, his visa application to Italy was rejected.

Ironically, the dearth in materials, infrastructure and training opportunities have proven liberating to Odur. “When I began my career, I was not thinking industry,” Odur asserts. “I was thinking about what my art is about.” Focusing too much on the opaque personal networks of the arts industry, he finds, can put an artist in a corner. Whether Uganda’s current arts sector will be able to sustain Odur’s artistic career is a different question, despite his international successes. Given the state’s active monitoring of cultural production, and Odur’s political commentary with his art, he finds the current political climate in Uganda stifling for his practice. When asked where he sees himself in ten years from now, Odur quips with a gallows humour popular amongst Ugandans discussing politics: “I think I’ll be arrested.”

Anna Adima is a German-Ugandan culture writer and journalist based in Kampala, Uganda