A police car parked up at an art fair in São Paulo created a collision: a symbol of state violence brought into the monied artworld

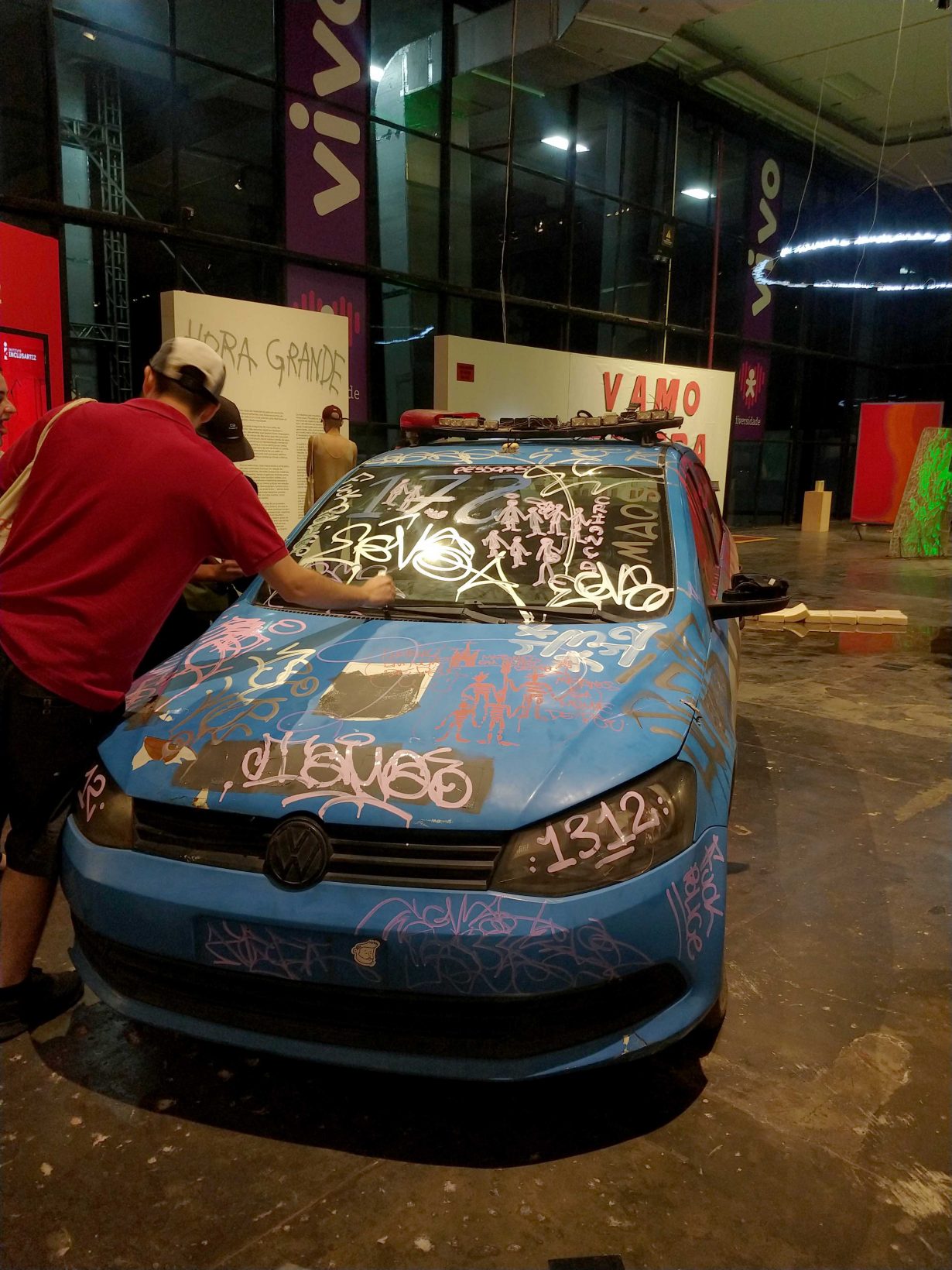

On the ground floor of the pavilion hosting SP-Arte, a recent art fair in São Paulo, a police car was parked up inside the building. You could tell it had come from Rio de Janeiro by its blue, white and grey paintwork, but its insignia had been roughly painted over, its siren smashed in and its interior rendered a mess of torn seats and trashed mouldings. It looked like it had been caught up in a riot. The reason it was here, however, is because it had been procured and was now being exhibited by Allan Pinheiro, an artist from Complexo do Alemão, a favela in the north of Rio, as a crude symbol of his and his neighbourhood’s often fraught relationship with the city’s security forces.

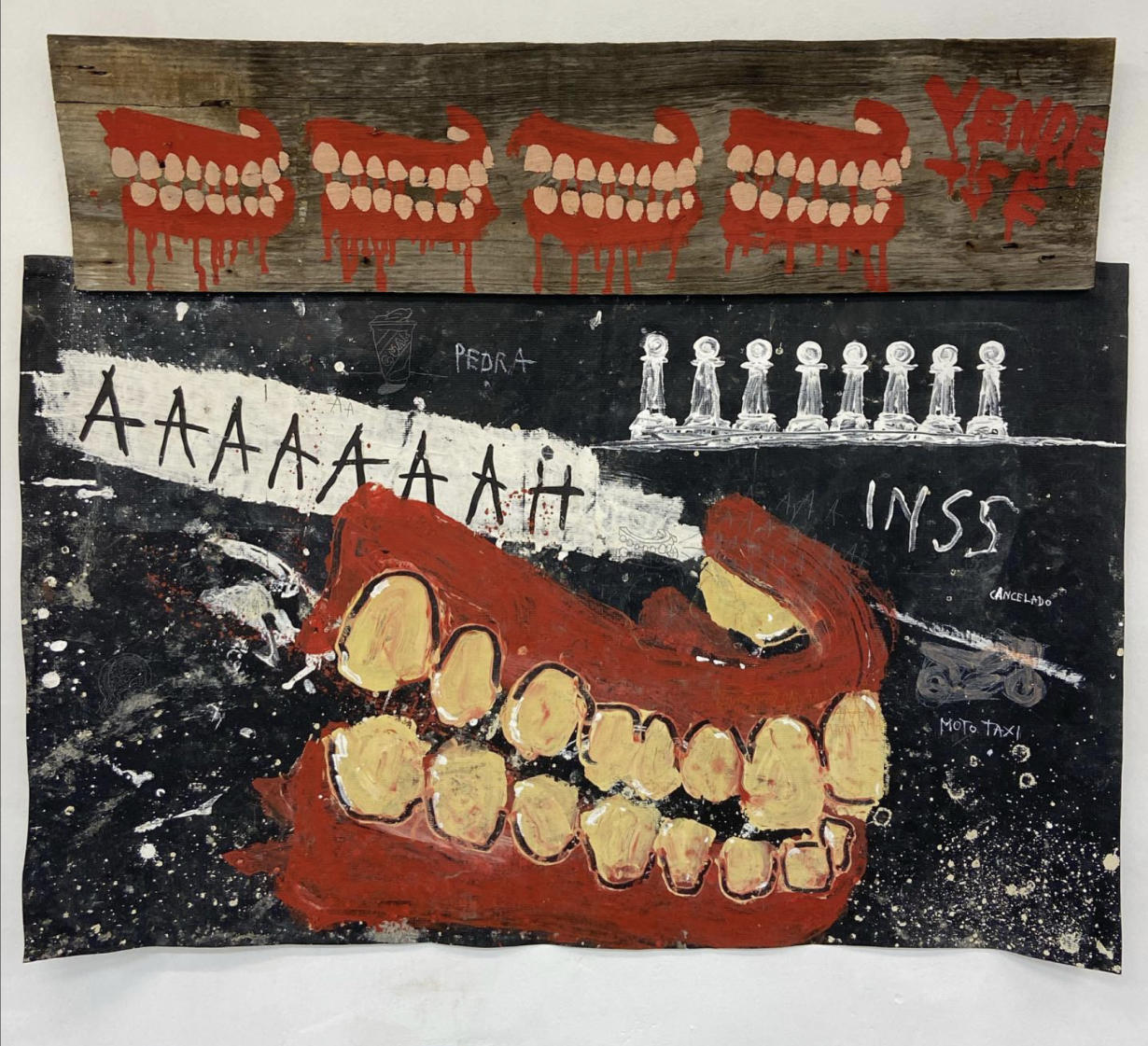

Pinheiro has garnered attention for himself in the last year as a painter, often working on found scraps of discarded wood as much as canvas to document the vernacular motifs and aesthetics of his surroundings. His text-based paintings reference the rough signs that advertise taxi services or car washes, while tanks, guns and mouths evoke the violence and disorder of favela life. One oil-and-graphite work, Produto de limpeza (Cleaning Product, 2021), shows a faceless police officer, the title a reference to the authorities’ often violent attempts to ‘cleanse’ the favelas of organised crime; endeavours frequently resulting in multiple casualties, among them children and bystanders as much as hardened criminals. A Cadeira (The Chair, 2020) is based on a press photograph in which a chair stands incongruously next to a bloodsoaked body as two gun-toting military police in balaclavas look on, the victim one of 12 killed in Complexo do Alemão that day.

The car sculpture, titled Fragments of the recent history of Brazil and Latin America (2022), is part of a corrective in which scenes of favela life, a daily reality for so many, make their way into Brazil’s galleries and museums (with all the contradictions and tensions involved in showing and to an extent commodifying that imagery within such traditionally economically and racially coded spaces). Maxwell Alexandre’s paintings have been the subject of various institutional shows here and internationally: Só quando tu tá com folhas geral gosta de salada (Only when you have leaves do you tend to like salad, 2018) is typical of his largescale paintings on paper, shown unframed and freehanging like curtains from the ceiling. It depicts the material aspirations of the artist’s peers (fast cars and stylish clothes) alongside one small detail: a woman with a pram aiming a kick at a police car’s window, a moment of frustration against a system in which wealth is often denied. The police are also a frequent motif in the work of Jota, who is from another of Rio’s favelas, often pictured in scenes featuring the artist himself.

Yet Pinheiro’s police car, like the artist’s wider practice, is more than mere representation. The artist has written that he is interested in exploring the ‘different social realities’ of a typical Brazilian city, encapsulating not just the life of the poorer factions of society, but the moments in which different classes briefly, and unequally, interact. Pinheiro often hangs his paintings so that they overlap each other in a kind of bricolage, indicative perhaps of how the lives of car washers and Uber drivers and other such personnel overlap social spheres, ricocheting between the wealthy realms in which they provide services and the precarity of life at home. The police car at the fair represents a similar collision: a symbol of state violence brought into the monied environs of SP-Arte (for most of those visiting the fair, the car will be the nearest interaction they have with the police). Now of course the art market has infinite capacity to neutralise all commentary through co-option/assimilation and turn it into commodity, and the car proved a hit on social media, with many of the linen-clad middle-class fairgoers happily posing for selfies. But then something else happened: by the weekend a graffiti artist named Massive Mia defied security to spray ‘Mother Child Police Kill’ across the car’s exterior. More came, playing a cat-and-mouse game with fair staff, sneaking spraypaint through the doors, until the vehicle was a mess of political slogans and artist symbols. The work was elevated beyond mere representation of the gulf between Pinheiro’s community and the artworld, to a living battleground, a social sculpture in which the gates to the artworld were breached. There were still selfies, but this time it was the taggers themselves posing next to their handiwork.