Black Melancholia at CCS Bard, New York mines the blues – literally and metaphorically – to examine the haunting wounds of the past

Recent years have witnessed the increased importance of melancholy in radical Black theory. Some theorists, such as Stephen Best, view melancholy as part of attempting to recover the irrecoverable past, an affective response to the collective traumas of Black people. Others, like Joseph Winters, think of melancholy as a ‘return to a wound that can never be sutured’, a lost object that can never be ‘anything other than a ruin’. Featuring the work of 28 artists of African descent, Black Melancholia deftly crystallises these theoretical currents.

The blues, literally and metaphorically, becomes a key theme for the exhibition’s design. Black Melancholia begins through a cerulean portal: glass doors, tinted by blue transparencies, open to an azure-carpeted gallery filled with representations of anguish by twentieth- century Black artists. Paintings, drawings, sculptures and prints all depict Black subjects in poses of hunched and agonised introspection. In the centre of the room, a dyad of sculptures occupy a circular plinth: William E. Artis’s The Quiet One (1951) and Selma Burke’s Despair (1955–67). The motif of the curled wretch, memorialised here in limestone and bronze respectively, and repeated elsewhere in the gallery, suggests that Black artists have long been invested in representing their pain via gesticulated melancholy because it is so intrinsic to their experience of the world. The persistent image resonates with pathos, making an empathetic appeal to viewers, who would have difficulty denying this art historical wave of pensive despair.

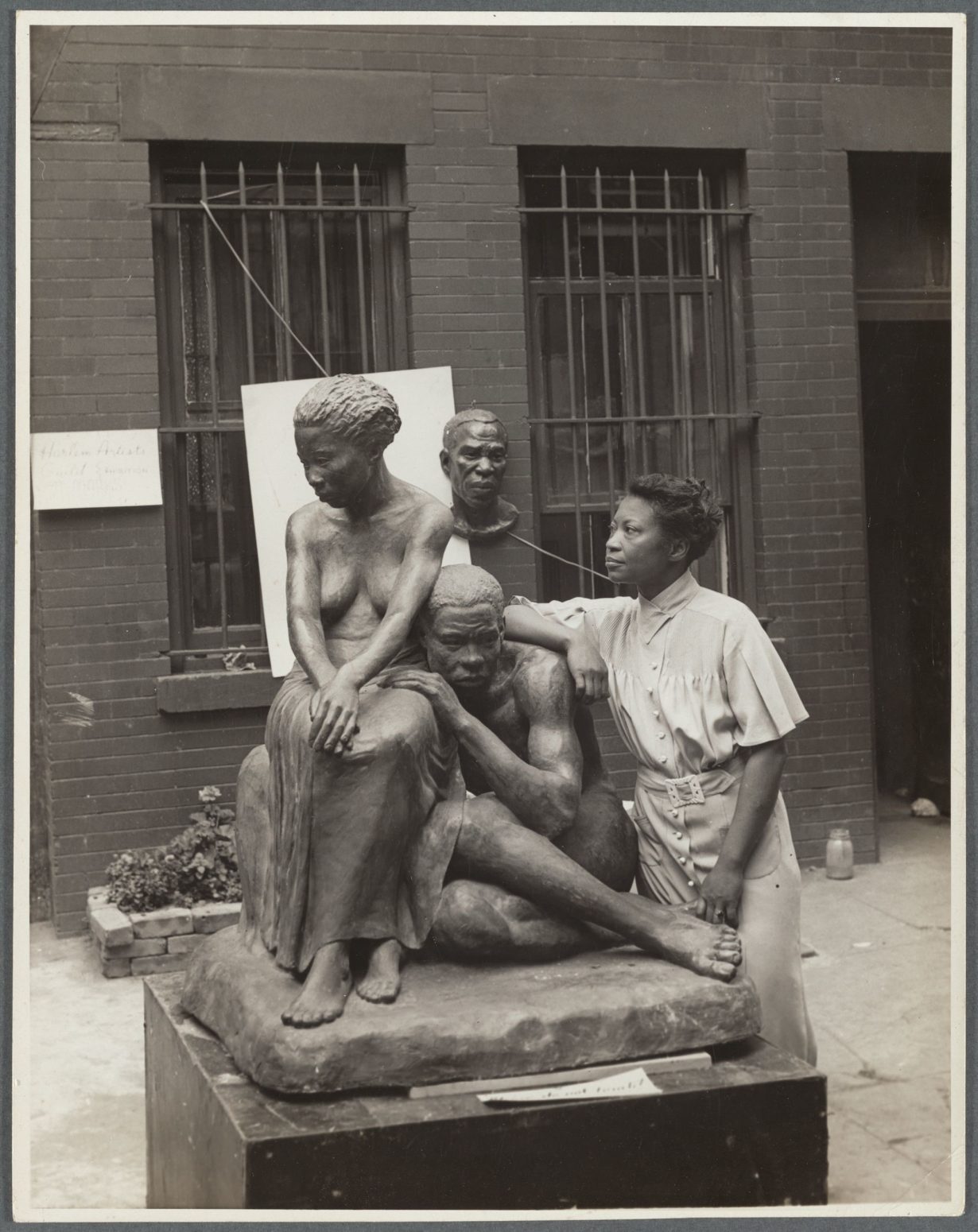

In the same gallery, three photographs float on a white curtain of gauze, and point towards melancholy’s vanished objects and the impossibility of their resuscitation. A now-anonymous photographer documented three views of a now-lost sculpture: Augusta Savage’s Realization (c. 1938), an allegorical, lifesize bronze of two former slaves. Seated in intimate exhaustion, the woman and man manage to lift their heads and gaze outwards at an unknown future, capturing the moment they realise their freedom from the bonds of slavery. A history, twice lost.

The endurance of pain emerges as a key theme. Ja’Tovia Gary’s video collage Giverny I (NEGRESSE IMPERIALE) (2017) contrasts the leisure of Monet’s gardens with other clips, from the searing reality of Philando Castile’s murder at the hands of police during a traffic stop in Minnesota in 2016 (horrifically live-streamed by his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds) to Fred Hampton, the assassinated Black Panthers leader. Idyllic visions of waterlilies splice with moments of colourful glitch and images that document police violence against Black people. Pope.L’s The Great White Way (2001–06) captures the artist’s epic performance as he crawled up the entire length of Broadway, satirising the American myth of upward mobility. Arcmanoro Niles’s Love I Try Even Though I’m Going to Fail (Rock Bottom Was Calling My Name) (2020) beams moody and tender intimacy. It is a book-size portrait of a bearded Black man, perhaps a love lost, radiating with pink and red undertones that glow from beneath his amber skin. The subject’s hair dazzles with glitter. In its title the work suggests heartache and the inevitability of loss. Melancholy becomes a psychological consequence of the torrent of live-streamed videos of police violence against Black people; of the racist ghosts of Jim Crow; of the hierarchies and laws that enshrine the status quo.

After the black-and-blue-painted galleries, the exhibition concludes in a white cube. While the Black figure is prominent throughout Black Melancholia, the final room turns to abstraction. Rashid Johnson’s Ask Ellis (2012) and Charisse Pearlina Weston’s of the. (immaterial. black salt. translucence) (2022) use different modes of abstraction to engage with the tides of melancholy. Weston’s installation of rippled glass sheets and vellum (supported by benches the artist’s father made) becomes a landscape of poetic text and image. Ask Ellis is a signal example of Johnson’s ‘cosmic slop’ work, a series that floods black wax, black soap and shea butter over wood flooring. Crowned with an oyster shell, five copies of Ellis Cose’s The Rage of a Privileged Class (1993) – a text that considers the anger of a Black middle class that continues to encounter racism daily – stack on a small shelf affixed to Johnson’s panel. Now a decade old, Ask Ellis becomes contextualised anew through Black Melancholia, and by the events of the past few years. The decades have advanced – 1993, 2012, 2022 – and with them inequality. Rage, and something much quieter, but no less psychologically encompassing, persists: the wounds and ruins of the past, haunting us now in hopes that we might be better attuned to others’ suffering.

Black Melancholia at CCS Bard, Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, through 16 October