What’s on display, if that’s even the word, is visual muzak

There’s a certain type of exhibition that I encounter a few times a year, even in supposedly ‘good’ galleries, and I’m always surprised how happy I am to see another example, given that the art itself is technically second-rate. It’s the type of show – always in a well-appointed, high-ceilinged white cube – that makes you feel like you’re in a gallery in a Hollywood movie. The artworks in such situations tend to be replete enough with familiar genre signifiers that mainstream audiences will infer serious creativity: big, hazy, slightly anonymous abstractions, like the anachronistic Ab-Ex painted by Nick Nolte’s character in New York Stories (1989); gaudy and cartoonish figurative painting; tastefully bulbous sculptures, etc. Everything looks like a prop and fades into the background, you can try parsing it but there’s nothing of interest to grip onto. It leaves you to get on with feeling like you’re a character in a scene, maybe staging an explosive argument with your companion against the backdrop of a big colourfield canvas. What’s on display, if that’s even the word, is visual muzak: undemanding, kind of pacifying. A break, that break you needed, from really engaging.

Now, this kind of show has been around forever, it seems. But that mood, acquiescence to softness and drift, is increasingly more widespread in art and culture generally. The writer Kyle Chayka has noted the rise of ‘ambient TV’ (‘sympathetic background for staring at your phone,’ he called Emily in Paris) and, lately, of a ‘vibes’ aesthetic, a foregrounding of sumptuous atmosphere, on TikTok. And while ‘ambient’ as a musical form has been around since the 1970s, contemporary pop is now ambience too: in the last of these columns I mentioned the parallel turn, burgeoning in recent years, towards unchallenging sounds that easily fade into the background while you’re doing something else. Raise your hand if you think this calculated lack of challenge to the viewer or listener might be partly related to the pandemic. It’s a variant, too, of the care imperative, considerate culture for a world that is generally hurting enough, can’t concentrate, doesn’t need another pressure, and also abhors silence – that is, being alone with your own thoughts.

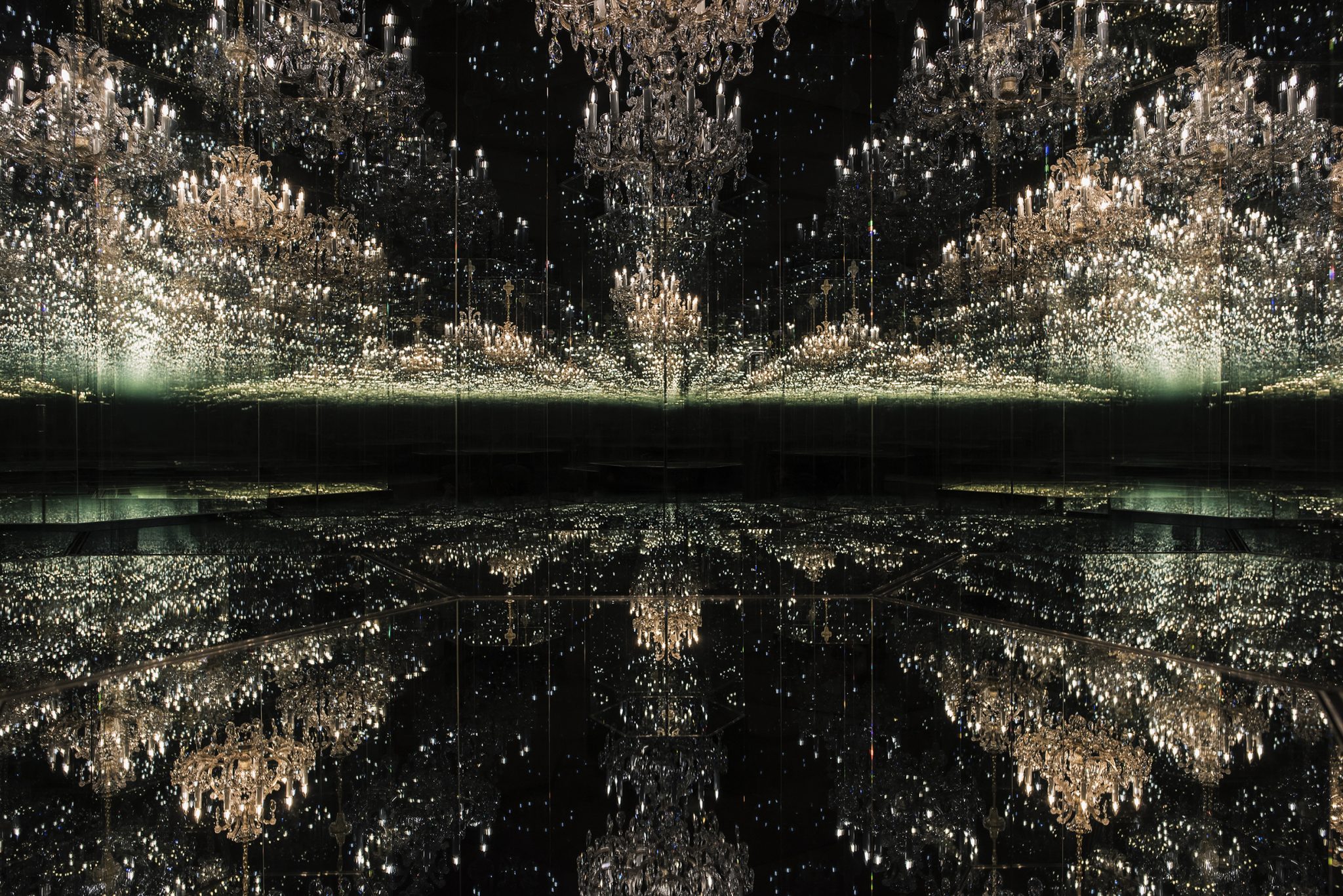

When this fleece-lined offer shows up in recent art, it does so in a few ways. Partly via deep familiarity, in exhibitions that might offer a bit of challenge with the first work but then only serve up variations on it, like a melody repeating, or a grip on the shoulders that melts into a hug. But it’s more prevalent in immersive installations, which – as per the warm-bath epithet ‘immersive’ – tend to lack a single point of focus outside of yourself, the viewer, the meandering and participatory individual having your own experience at your own chosen speed. When you’re within the mirroring dots and pumpkins of a Yayoi Kusama show, or surrounded by swirling clouds and digital garlands courtesy of teamLab, you’re unlikely to feel tensed up, for better or worse – unless, for reasons of personal taste, your teeth are on edge. There’s not much worrisome ‘I don’t get this’ – unless, in the high-end cases, you really want to know what specific technological innovations you’re being caressed by and triggering.

Rather there’s the sight of artists and curators responding to the fact of galleries and museums being backdrops for the ’gram, and to expanded audiences who don’t want to be made to feel stupid, otherwise they’ll stomp out without stopping at the café and gift shop and won’t buy a ticket to the next floaty spectacle. But also, if you’re feeling generous, other factors are in play too: this kind of art, that commingles entertaining qualities with some serious intent, might speak to audiences used to slaloming between information and education on social media. Plus, relatedly, there’s the notion of diffused attention, rather than focus, being a somatic register that serious visual art previously hasn’t really taken seriously – the forerunners of immersive art, like James Turrell, aside – and now, in some cases, that’s happening. And it will evolve, no doubt, likely underwritten by tech money.

It’s been widely suggested by technocrats that new technologies generate and demand novel styles of attention (even if it’s debatable how much adaptation our hunter-gatherer brains can really manage). If being doggedly undistracted suited the era of the standalone analogue book, the interconnected present and near future seemingly call for nimble, pivoting, improvisatory, associative cognition. There’s already been a fair amount of now-near-canonical art that played into such a modality of thought, from Ryan Trecartin’s mid-aughts early works to Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013) and beyond; but its freneticism, at least, seems recherché in (more fancy French words ahead) our nouveau son et lumière moment, It might be a marker of our fraught times that a significant swathe of art is recasting itself not as a training ground but a refuge, or at least a space where distributed attention can be experienced soothingly. Either way, the highest goal here is not the old model of sustained focus – art as more work for the viewer to do, no matter what the rewards. It is, so to speak, chilling.