A new display of ‘Holocaust letters’ reveals the ways in which real people become entwined with catastrophe – and challenges our understanding of ‘normality’

For reasons both understandable and elusive, our culture is generally in quite an ‘apocalyptic’ headspace right now. It’s not even just the climate crisis, or the pandemic, or resurgent threats of nuclear war: it’s that every election always seems to represent the final battle for everything; that any minor inconvenience can be spun out on social media as the catalyst for the end of all things.

And this has increasingly got me thinking: if an epochal disaster really was, finally, upon us – how would we know? I mean, obviously, if the waters rose and you couldn’t return to your home, or the Generalissimo’s men came round to evict you and shot everyone who dared to resist, well, you’d certainly know that something was up. But how would you know that this was the big one: the point from which nothing could ever, for anyone, be normal again?

I don’t know if this is the sort of question that really yields an answer; I’m not quite sure that is how history works. Some things are probably too big and complex for us to conceptualise as we’re experiencing them, anyway. But certainly, it’s one that came to mind while viewing the Wiener Holocaust Library’s current exhibition, Holocaust Letters, on display in London through 16 June.

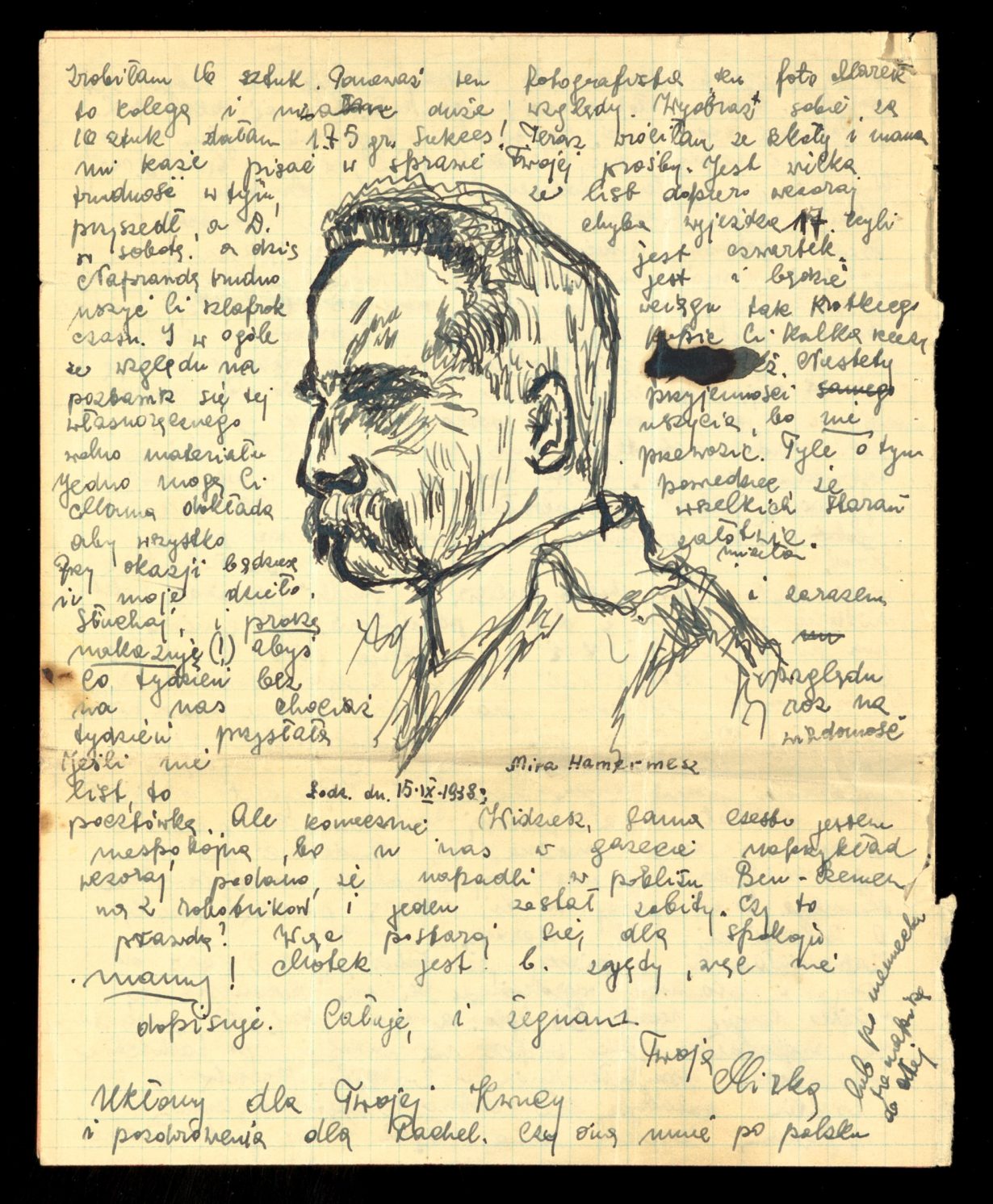

Written between friends and relatives from around 1937 to 1947, the letters communicate what I suppose we might call the everyday reality of the Holocaust, as experienced by its victims. Indeed, what I found most striking about the letters is how ordinary so much of their contents are. One hears the phrase ‘Holocaust letter’ and expects a lengthy discourse on the nature of the tragedy. But these ones exchange gossip, relate family news (even happy family news); they have cartoons scribbled on them, accompanied by phrases like “viele küsschen von Deiner dich liebchen Ilse” (“many kisses from your dear Ilse”). One letter, from September 1938, is incongruously centred around a large drawing of Nietzsche.

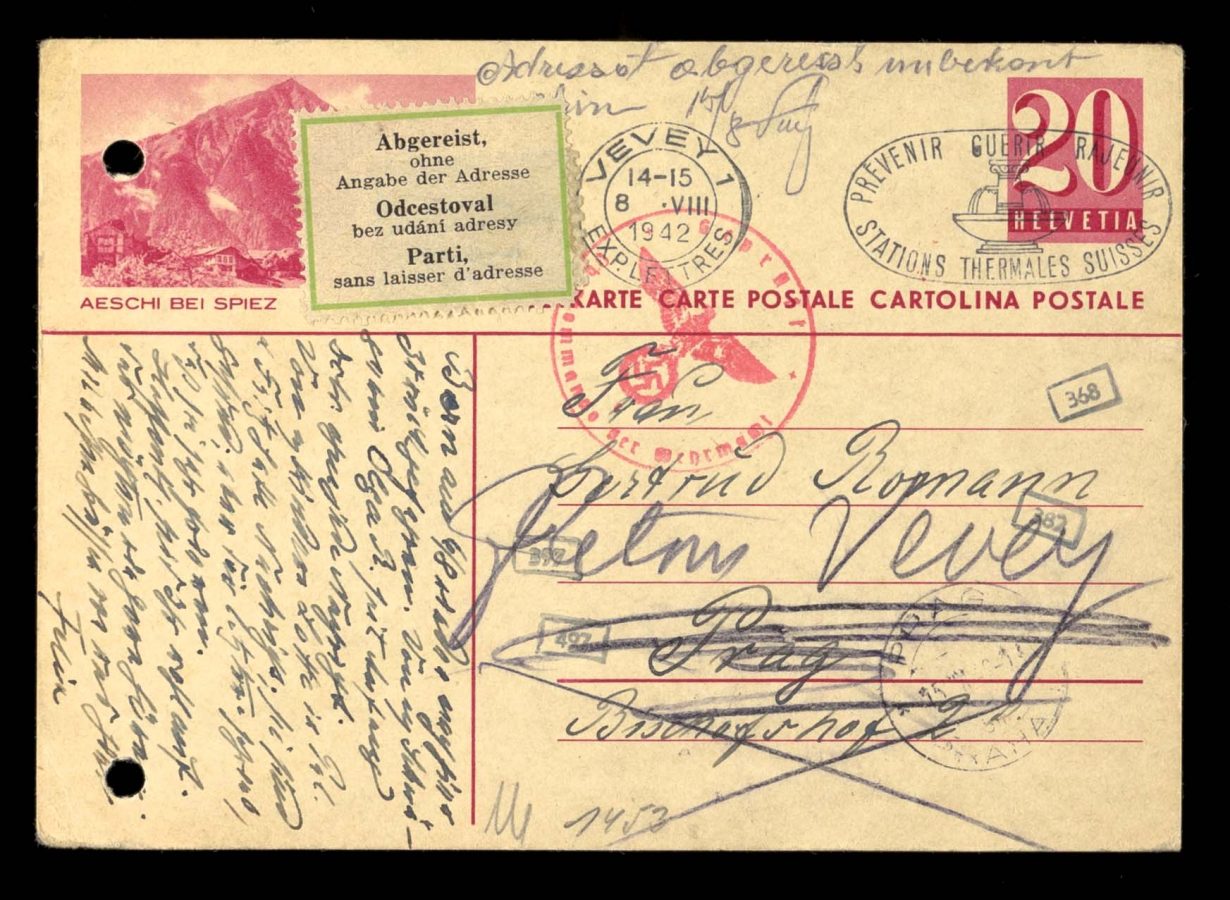

Sometimes, the letters do contain something momentous: one particularly striking example is addressed from the parents of a Kindertransport refugee to the child they hadn’t seen in seven years – somehow all three survived. But for the most part they are written by people who know that something bad is going on, but not its precise extent: they refer abstractly to “all this” or to “the catastrophe”; they refer euphemistically to “going to Poland”. Equally, however, the need to be coded was often forced by the fact that the letters were expected to be read by censors – both German and British. As objects, the letters will elude almost any visitor to an extent: some of them are accompanied by translations, but usually not complete ones; even a visitor both equipped with the requisite language skills and willing to squint at the handwriting might be undone by the fact that only one side of the paper is on display.

If there is some great lesson that this exhibition teaches us, it is that disasters like the Holocaust were things that happened to real human beings – human beings whose lives were not simply consumed by the catastrophe, but rather became entwined with it; who seem to have been driven to find something to call normal, or to find familiar, for as long as they possibly could.

So if there is an answer to my own question in all this, then it is probably something like what Walter Benjamin, himself among the most famous victims of the Holocaust, wrote in his final essay, ‘Theses on the Concept of History’, published posthumously after his suicide on the Franco-Spanish border while fleeing the Nazis in 1940. ‘The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule.’ Benjamin never lived to realise the full extent of the Holocaust – but nothing he can have experienced would have necessarily felt like a radical break from currents in western European politics from the Dreyfus Affair on. Here, I take it, is what Benjamin is challenging us to think, and what these letters in their own way help confirm: why think that any of this would involve ‘normality’ being suspended at all?

And yet – for an exhibition that arguably, subtly, tells us that everything we have ever experienced is implacably bound up with the worst sort of suffering, barbarity and oppression – one leaves it feeling strangely hopeful. As objects these letters – written for the most part in a form of German cursive that is no longer taught, to loved ones mostly long dead, often on whatever scraps of paper could be found – after all, survive. They come to us from a world that was destroyed in the most brutal way possible. But many of them have now survived for long enough to become family heirlooms (much of what is on display here was donated by families, including that of the author Michael Rosen). This is something worth marvelling at in itself: that enough people survived this for its memory to be possible.

The fear, though, is that this marvel is now being squandered. As Benjamin’s great friend Theodor Adorno remarked, the imperative forced on us by what happened at Auschwitz is to arrange our thoughts and actions to ensure that nothing like it can ever happen again. Perhaps this explains why we nowadays have such a nagging sense of the apocalypse: that we have, whether from complacency or something much worse, acted on this imperative far too little.