The ‘Black is Beautiful’ movement; Velázquezian references; Sleeping Beauty – it’s all there in Marshall’s monumental painted worlds

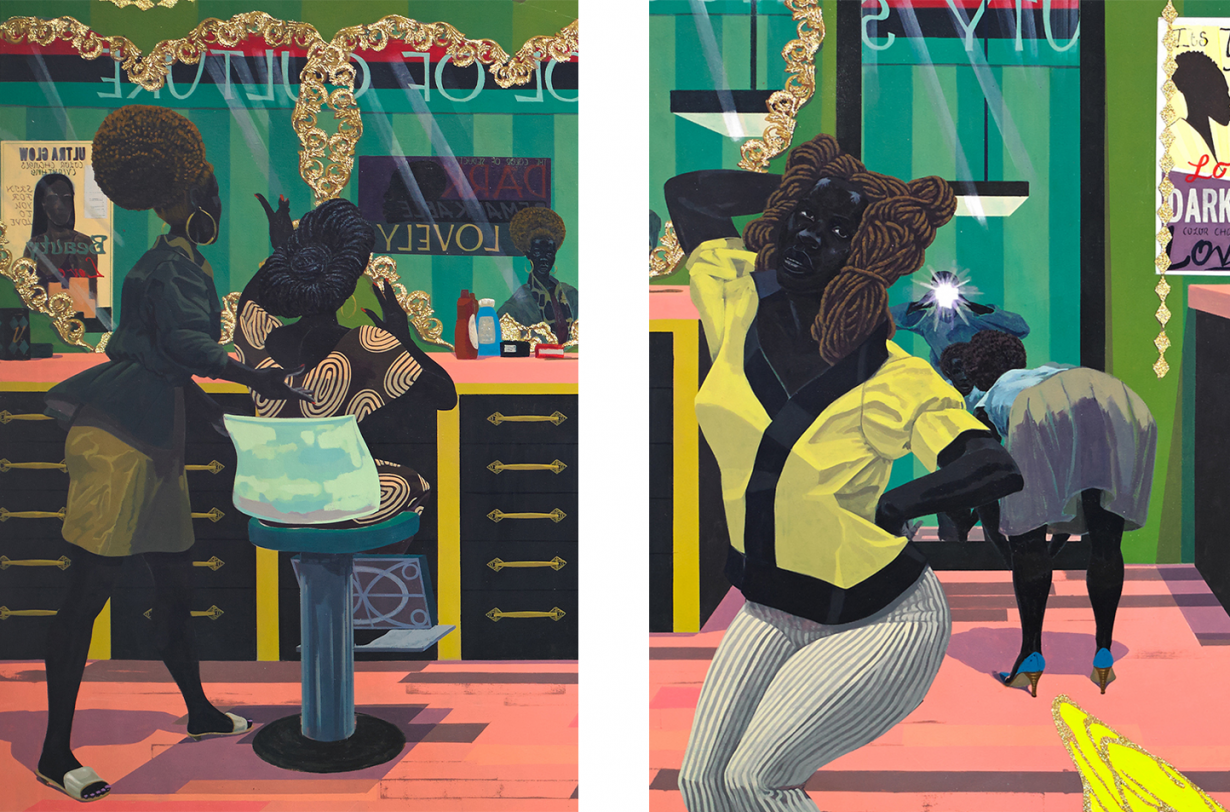

‘The figures in my paintings are not naturalistic in the conventional sense. They are rhetorical figures that inhabit a realist space,’ Kerry James Marshall told the art historian Benjamin Buchloh, ahead of the artist’s survey The Histories, at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Marshall has spent his career restoring Black figures – in the form of figures whose skin is literally black – to the Western art-historical canon. He has his Black figures perform a discursive function – that of filling a visual and epistemological void in the histories and institutions of art left by the historical exclusion of Black self-representation. He states, in the same interview, that ‘using black paint to paint Black figures is not at all about representing Black subjectivity’. As a rhetorical device, the black skin he renders on canvases, often monumental in scale, does not on its own give form to the nuanced and particular emotional lives of individual Black Americans. What is peculiar about his Black figures, however, is how easy it is for them to exceed their roles as operatives in Marshall’s reparative project and insist on being read like characters in a play, film or documentary – that is, as genuine Black subjects with their own emotions and drives. Take, for instance, the glamorous, self-possessed Black women who fill the bustling salon in Marshall’s mural-size acrylic painting School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012).

Featuring 13 Black figures – including the artist, who appears behind the flash of a camera, Arnolfini Wedding-style, in a full-length mirror – School of Beauty captures a roomful of refracted energies, scattered attention and freefloating desire. In the foreground, a woman in a yellow wrap top and tapered grey corduroy pants, whose skin is jet black, poses for Marshall’s camera. On one hand, she represents the condition of Blackness in the abstract; on the other hand, this figure clearly has her own personality: see how she’s made herself the main character of the tableau, a star under the salon’s beige troffer lights. The artist-as-cameraman, too, has a personality: instead of centring the woman in yellow in the composition, his mechanical eye drifts down and to the right, distracted by another woman in a light-blue blouse and khaki skirt, who is bent over with her back to him. From there, other threads of narrative tension emerge. A pair of toddlers innocently examine the surreal anomaly that is the anamorphic, Hans Holbein-esque head of Disney’s Sleeping Beauty stretched across the painting’s centre foreground. In the background, a hairdresser in a red-and-gold brocade jacket is attending to a client reclined in a salon chair but, distracted, turns and reaches towards the foreground. On the other side of the room, another beautician in pearly sandals and gold hoop earrings, who appears to be consulting her seated client, is meanwhile making quiet, forceful eye contact with Marshall’s lens in her styling station’s heart-shaped mirror.

Yet no matter how lively, how charismatic and assertive the Black women in School of Beauty appear, how engrossed they seem to be in the drama of their mise-en-scène, their bodies nonetheless look posed in a way that insinuates a secret affinity with objecthood. Consider, for instance, the stiff and angular hand gestures of the woman seated at the styling station near the left edge of the composition. On a practical level, this can be explained by the fact the artist bases his black figures on dolls rather than on live models. In an essay for the Royal Academy’s catalogue, Madeleine Grynsztejn, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, describes how, during the late 1990s, Marshall began amassing a collection of Barbie dolls and action figures. ‘To clothe them,’ Grynsztejn reports, ‘Marshall… taught himself to sew, and over time created hundreds of miniature garments.’ According to Mark Godfrey, one of the curators of The Histories, the figures in School of Beauty wear ‘clothes based on garments Marshall had made himself to ensure the figures looked unique’. In fact, one of the women, who stands with her ankles crossed in a blue patterned sundress, has her origin in a Black Barbie in Marshall’s studio (the catalogue contains a photo of the doll wearing a miniature version of the dress). The question becomes, then, how Marshall’s painting manages to flesh out its ‘dolls’, to make them appear to have desires, motivations and emotional lives, when the doll is practically synonymous with the notion of female objectification. The answer may lie in the figures’ distinct sartorial flair, a product of Marshall’s meticulous attention to the ornamentation of their bodies. The finger- and toenails of each woman are varnished in either vermilion, seafoam green or lavender; the gold hoops worn in their ears vary in thickness and diameter in accordance with their attire. The explicit embrace of glamour, of personal style, thus becomes the canvas’s mantra, an actualisation of cultural theorist Anne Anlin Cheng’s proposal that ‘flesh that passes through objecthood needs ornament to get back to itself’.

Step back from the individual figures, and School of Beauty speaks in the manner of a body draped in garments and accessories, or hair arranged in a laborious updo: it is semiotically encrusted, laden with allusions to art history’s greatest hits – from Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656) to Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) to Chris Ofili’s Blossom (1997) – which have been extensively analysed by Marshall’s critics and curators. In the middle of the composition, a poster depicting the silhouette of a Black woman overlaid on yellow sunrays, beside the phrase, ‘It’s Your HAIR!’ and the words ‘DARK’ and ‘Lovely’, seems to have been put in place to counter the white beauty standards epitomised by the ghoulish face of Sleeping Beauty. This and other accoutrements of the salon hark back to the aesthetics of the ‘Black is Beautiful’ movement of the 1960s and 70s, giving us additional glimpses into the cultural context and inner worlds of its workers and clientele. Ntozake Shange’s For colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf (1976), a text often associated with ‘Black is Beautiful’, seems embedded in Marshall’s painting vis-à-vis its polychrome palette and, when read against School of Beauty, illuminates something about the relationship between ornamentation and subjectivity at play here. In Shange’s ‘choreopoem’, seven Black women identified by the colour of their clothing – they’re called, for instance, ‘lady in yellow’, ‘lady in blue’ and so on – deliver monologues about their experiences of objectification and mistreatment. They describe being catcalled and stalked in public places, physically and sexually abused by lovers and friends, and how, for them, ornamentation operates as a self-protecting and self-constituting artificiality, a bulwark against the ‘metaphysical dilemma’ that is, as Shange’s ‘lady in yellow’ puts it, ‘bein alive & bein a woman & bein colored’.

In one particularly moving monologue, a ‘lady in red’ speaks about a woman, likely herself, who emblazons her face with rhinestones, decorates her stomach with ‘small iridescent feathers’ and invites ‘those especially / schemin / tactful suitors / to experience her body & spirit’, only to wash off the excess at four in the morning and shock her suitors with the sight of her as an ‘ordinary / brown braided woman’. In Marshall’s images, the former is no less authentic than the latter, and to get dolled up is not to be static and thinglike but to pose, to flourish and to be an active participant in the creation of one’s self-image.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories is on view at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 20 September – 18 January

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.