The renowned American conceptual artist was fundamental in decoupling art from objecthood, asserting that the idea was enough

One of the first things I see on waking is the phrase ‘A simple vector in the realm of concentricity / the middle of the middle of the middle of’. These words feature on a screenprint that hangs opposite the bed in which my wife and I sleep; they balance dynamically on French curve-drawn lines, while primary-coloured directive arrows point downward through the text. The work’s title is A SIMPLE VECTOR (2012) and the artist, as you’ve no doubt guessed, is Lawrence Weiner. Despite years of early-morning mental calisthenics, I’ve never gotten to the bottom of his phrasing here, a statement at once legible – designating and subdividing circular space (the print relates to a piece made for a rotunda) – and mysteriously unresolved (that final, dislocating ‘of’, for one thing). The language, sweetened by design, feels both weighted and intangible. Echt Weiner, in other words.

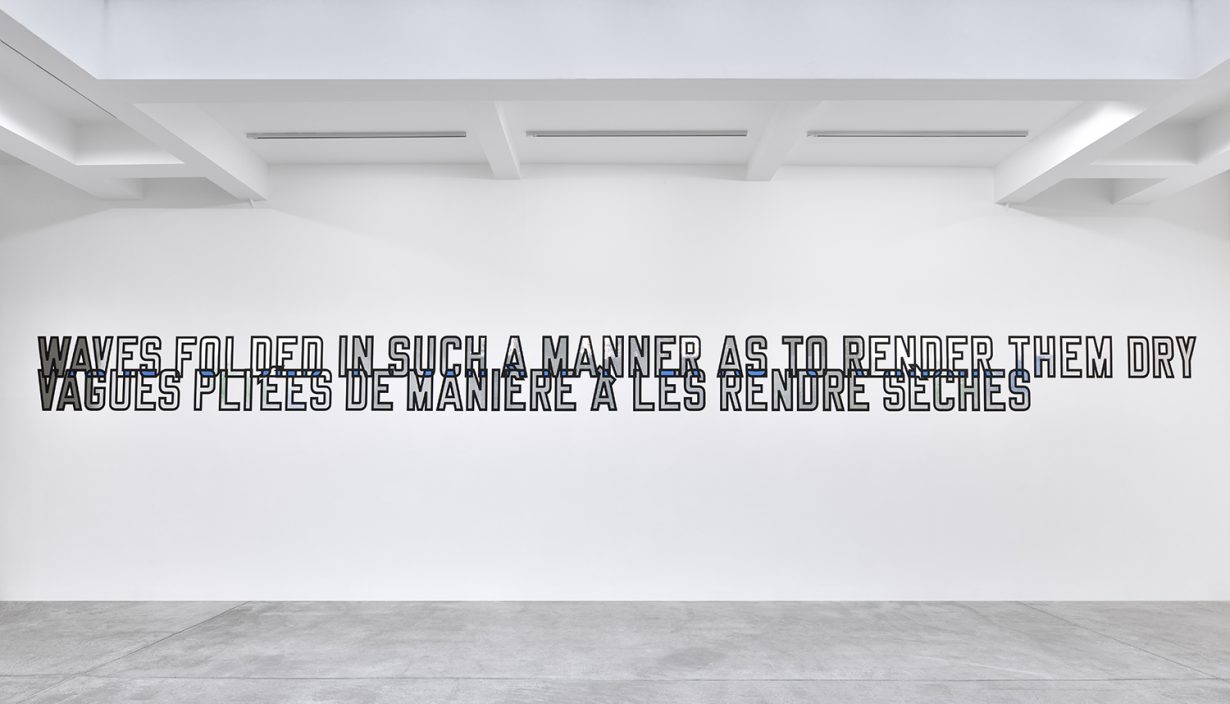

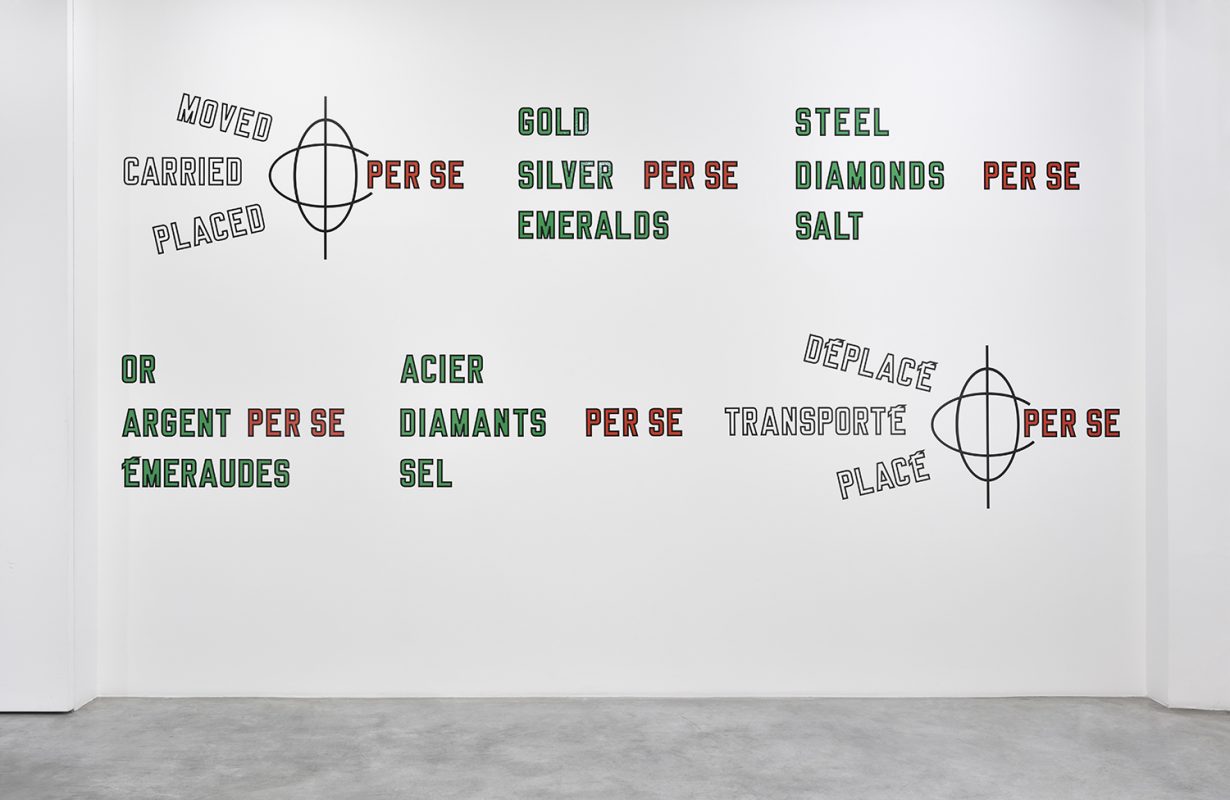

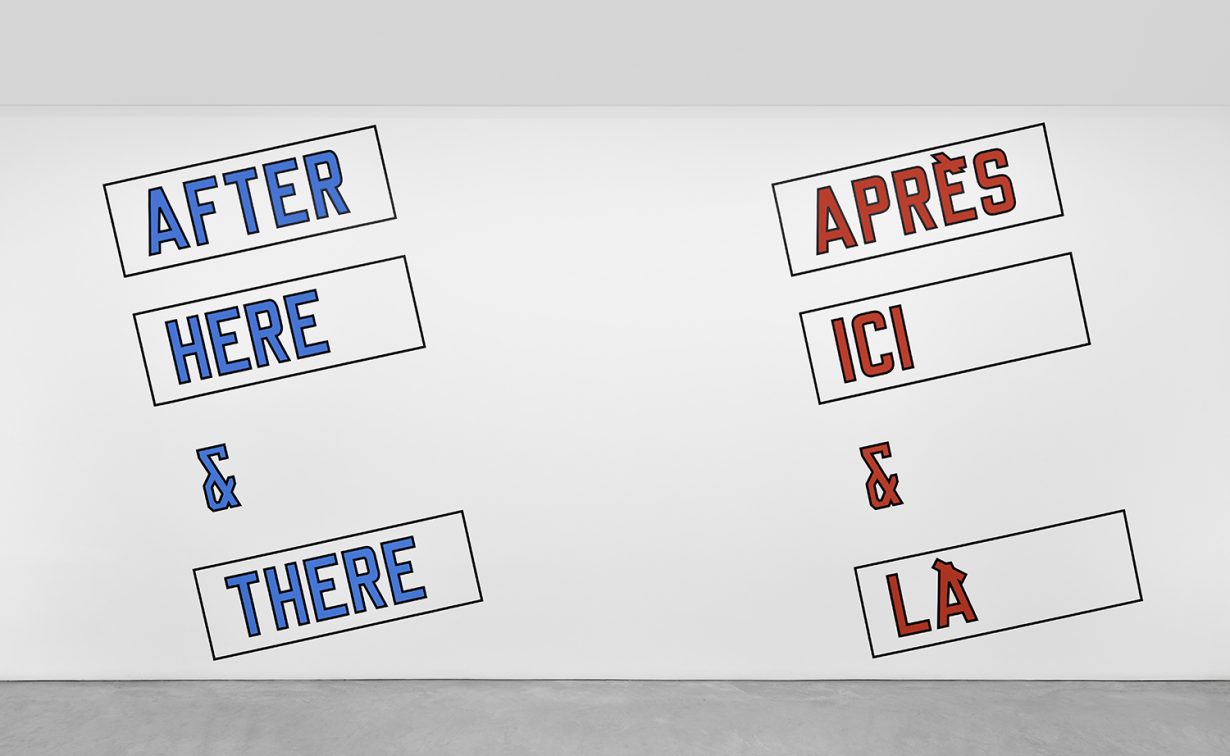

The renowned American conceptual artist, who died earlier this month at age seventy-nine, was fundamental in decoupling art from objecthood, asserting that the idea was enough. The three parts of his famous 1968 artist’s statement read: ‘1. The artist may construct the piece; 2. The piece may be fabricated; 3. The piece need not be built.’ Yet Weiner both redefined ‘building’ and delegated it. If you read one of his wall texts, either in a gallery or on an architectural façade – ‘A bit beyond /what is designated as / the pale’, ‘After here & there’, ‘Poised between dissolution and resolution / at the present time’ – you’re fabricating in your head, however abstract the result might be. Many of Weiner’s statements, it might be clear from just the above, have to do with getting somewhere, locating yourself somewhere else. Often – perhaps pointedly given that he worked in his early days on an oil tanker and on docks, and later often wore a naval hat blazoned with one of his own writings – they’re situated at sea. You might sense in them an impatience with the current state of things, either our drift on the ocean of the normative or our resistance to oceanic signification. There’s a sense that with enough mental leaping, things – starting with what an artwork can be – could be other. A sculpture might not only be the aleatory aftermath of an explosion – as Weiner posited in Cratering Piece, 1960, in Marin County, California, made when he was nineteen – but also an imagined object or place. Such violent ambition, you’d have to imagine, underlay the quote that’s been widely shared in the wake of his death: ‘The thing is, I don’t want to fuck up anyone’s life on their way to work. I want to fuck up their whole life.’

The one time I intersected with Weiner was in Oslo, 2006, for the opening days of a show that featured both first-wave conceptual artists and younger ones. He gave an oracular public talk, full of vertiginous pronouncements about the world-changing responsibilities of art and the artist, that met with vocal resistance from the younger participants, whom he’d successfully rattled. Onstage that day Weiner displayed a certainty of his own worth and radical indifference to being liked. (An artist who cared about being liked probably wouldn’t have made the various adult films he’d produced from the 1970s onwards, occasionally involving the artist sucking women’s toes: “I’ve always seen myself as a basic materialist which is why my films are so raunchy,” he said.) Dan Graham was at the Oslo event too, and the main thing the two titans agreed on was how much one other famous conceptualist – who shall remain nameless – sucked. Yet, at a drinks party on the same trip, Weiner was lugubriously funny and chatty, recalling his childhood in wartime New York (a diet of whale meat and Guinness, since his mother believed the alcohol dissipated if you left the drink open to the elements awhile). And this is closer to the gentler, off-duty figure, carrying his gravitas lightly and supportive of others – even relatively tenderfoot art critics – that many have remembered in the wake of his passing, the tributes illuminating how much Weiner’s supportive connections stretched down the generations.

As he and his coevals wink out of the firmament, so, it appears, does a whole seismic era when art could be and was radically rethought. Try and imagine a young artist enacting a category shift of the scale that Weiner was decisive in bringing about, and doing it with a similar generosity of spirit, an understanding that art is made by viewers of all kinds. Indeed, walking around any major city nowadays, you might have occasion to do so, because there are gnomic yet accessible text works by him speckling buildings all over the world, their phrases typically inscribed in both English and the host language. Weiner wanted to be read, to get up inside people’s heads: not just artworld people, but anyone who could read and had curiosity and was open to an infusion of poetics, meeting them on the democratic plain of language and suggestion. Weiner, as part of a narrative of love and theft that I’ve written about elsewhere, changed my own life without even knowing it. On the level of artistry, creative permission, and mind-expansion, he did so – and will continue to do so – for many others too.