Artists like to think they’re pushing boundaries, but in reality, transgression gets punished more than applauded – which is Gupta’s foremost subject

Every artist likes to think they are pushing back boundaries or crossing borders. That they’re riding roughshod over them even. That what art does is to demonstrate that borders, boundaries, rules and regulations don’t really exist. Except as constructs. In our minds. It’s what most art lovers like to think, too. The frisson of transgression is part of the attraction of the form. ‘The shock of the new’ and all that stuff. You go to a gallery and you can experience transgression without having to risk performing any yourself. Perhaps all this is also what allows art so easily to be posited as a site of privilege. A space within which the normal rules don’t apply.

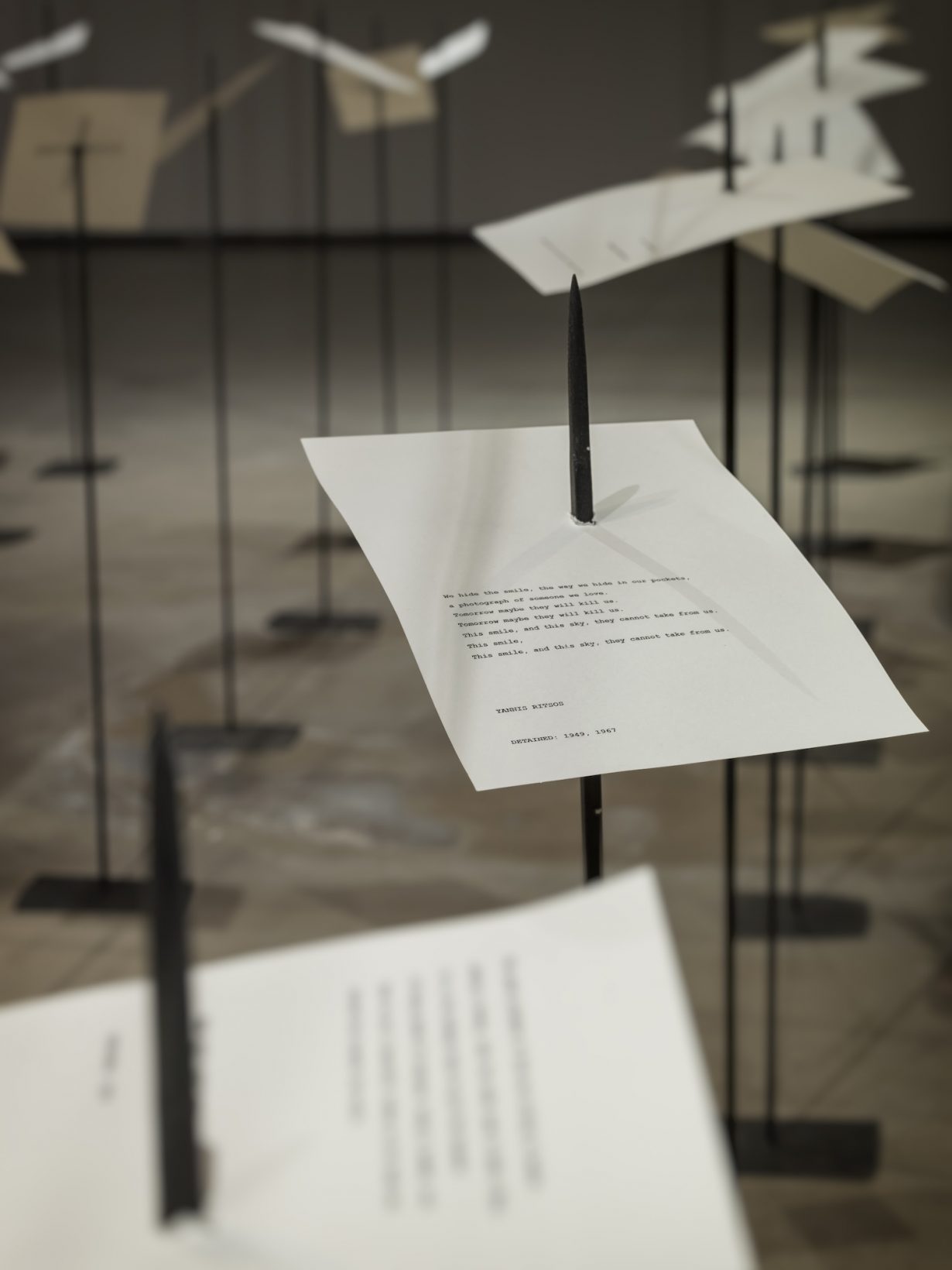

Of course, real life isn’t like that. People who actually transgress get punished more than they are applauded. Generally, by being sanctioned, imprisoned or even killed. That reality is the subject of one of Mumbai-based artist Shilpa Gupta’s best-known works, For, in Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit – 100 Jailed Poets (2017–18). It’s a multilingual sound installation that has been shown at the Edinburgh Art Festival and Ninth Asia-Pacific Art Triennial (both in 2018), at the Venice Biennale and the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (both 2019), and that features recordings (broadcast from microphone-shaped speakers suspended from the ceiling) of the works of poets who have been sanctioned for their writing or their politics. Underneath the microphones are A4 sheets of paper printed with verses and impaled on spikes, as if they had been measured by an angry accountant wielding a receipt spike (as in the Monty Python short film The Crimson Permanent Assurance, 1983), or a no less angry literature-hating Vlad on a rampage. Those writers range from eighth-century Arabic poet Abu Nuwas (imprisoned for drunkenness and failing to conform) to Nobel Peace Prize-winning Chinese human-rights activist and literary critic Liu Xiaobo (who died in 2017 after serving numerous prison sentences). The title of Gupta’s work derives from a poem by fourteenth-century Azerbaijani, Hurufi poet Nasimi, who was executed c.1418–19 by the Mamluk Sultan of Aleppo (at the instigation of the writer’s Sunni critics) for propagating his religious beliefs. Surrounded by an unruly order of different languages, it’s hard not to recall some of the tools of colonial oppression, particularly Thomas Babington Macaulay’s infamous declaration that ‘a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia’, uttered while he was president of a Committee of Public Instruction in Bengal (tasked with improving ‘native’ education). And, of course, you’re reminded too that the intimidation and suppression of writers is ongoing. Last year it was announced that India’s best-known living writer, Arundhati Roy, a frequent critic of successive national governments, was to be prosecuted under the country’s anti-terror laws for comments (made way back in 2010) regarding the disputed territory of Kashmir. For, in Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit…, claims Gupta in an interview that’s included in a book anthology that accompanies the project, is ‘about the persistence of beliefs, of dreams, which make us what we are as individuals’. Of course, the reason that these writers are sanctioned, imprisoned or killed is the fear that their beliefs might become a reality.

For, in Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit… is one of a series of works that circle

around a similar theme. Listening Air (2019–23) is another multilingual sound installation featuring protest songs and moving lights and microphones/speakers. Untitled (Spoken poem in a bottle) (2018–) features a series of labelled bottles into which the artist has spoken poems. Someone Else – A library of 100 books written anonymously or under pseudonyms (2011) features a selection of stainless-steel book covers of works that have been written under the conditions suggested by the title (but caused by the suppression of particular genders, religions, politics, and so on), spanning two centuries.

In a sense, you might view these works as gestural – they point to something, without necessarily being something in and of themselves. They point to the fact that you can’t constrain ideas or thoughts, perhaps. That you can kill a person but not an idea. That pens are mightier than swords. This list of clichés could go on. What links them all is the manner in which they are pronounced as certainties but conceal aspirations (that death is not as final as it might seem to the eyes of the living, for example). Indeed, which of those you swing towards might depend entirely on how you view the idea of life after death. But perhaps that also gets us close to something else that all art is about: belief. There’s no doubt that Gupta’s works emit a certain numinous aura.

But works like For, in Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit… also bring to mind historian Benedict Anderson’s notion of ‘imagined communities’ – his explanation for the spike in nationalisms that triggered the Indochina wars of the late 1970s, but a concept also born out of his ongoing studies of the relationship between language and power. Anderson’s communities were linked not by visual displays but by language and mass media (which at the time of Anderson’s writing, in 1983, meant newspapers). Reading them, Anderson suggested, ‘is performed in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion.’ Yes, it sounds like what most people are told they experience in an art gallery. And in that it is also about belief. Gupta’s work proposes something similar. Yet it does this in a way that transcends the level of geographic or linguistic barriers, the idea that it might form a community that might form a nation, pointing instead to a type of redemptive human essence or globalism. Which may seem naively optimistic. But art’s supposed to allow space for that too.

Meanwhile, the citizens of Ballymena in Northern Ireland are rioting and hunting down foreigners, Israel is bombing Gaza and Iran, India and Pakistan are exchanging missiles and bombs, members of Bangladesh’s largest political party are discussing the setting up of a Rohingya-majority state with members of the Chinese Communist Party (go figure), in order to ‘solve’ the Muslim country’s refugee problem, India is forcing residents of the Barpeta District of Assam across the border to Bangladesh at gunpoint on the basis that they might be illegal immigrants, the US is deporting everyone it can and even a few it can’t, and god knows what’s going on in the South China Sea.

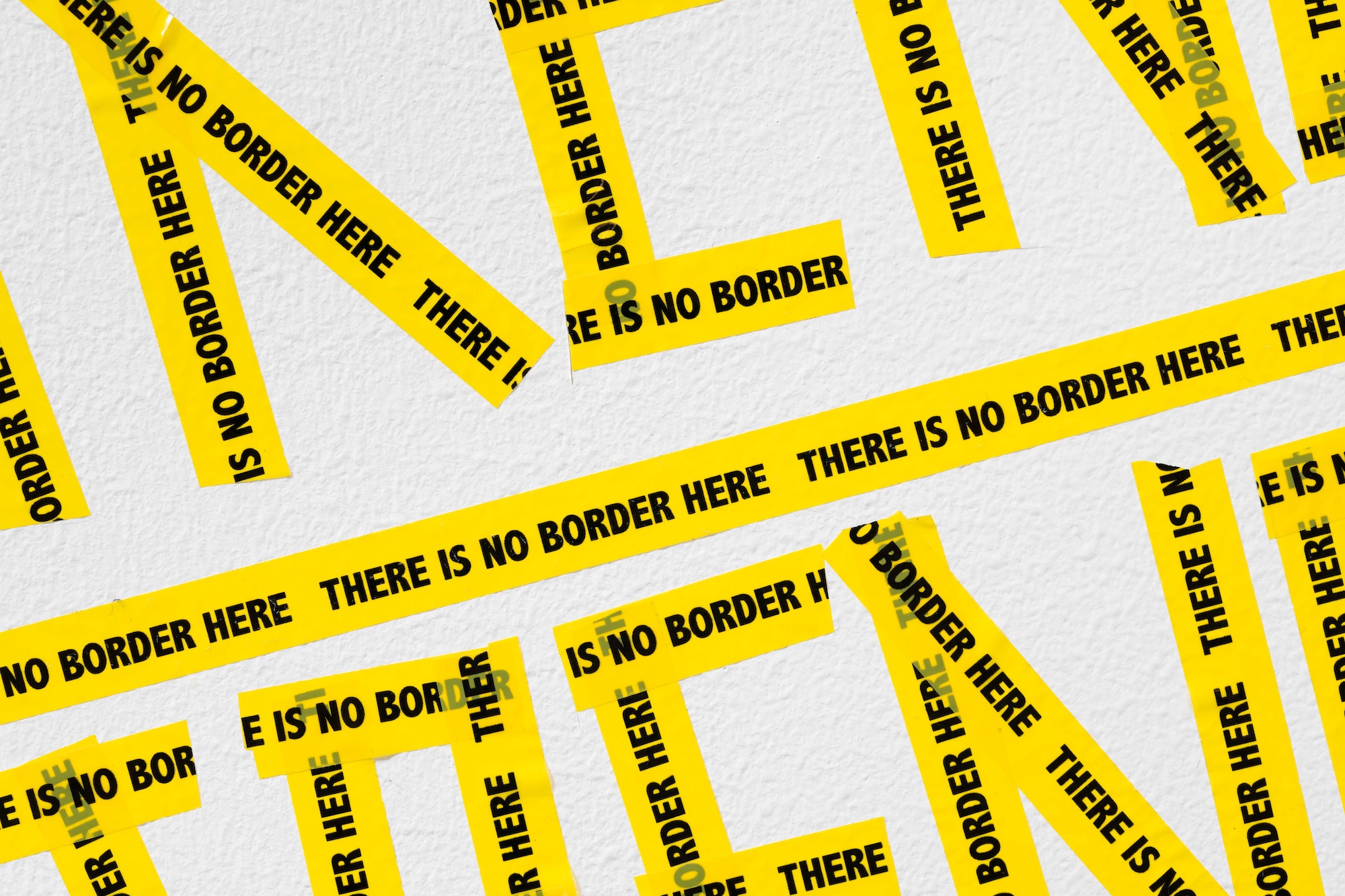

Gupta’s work doesn’t pretend all this isn’t there. Rather it focuses on ways in which such attempts to govern, segregate and categorise might be resisted. Key to this is the way in which, through her art – much of which was recently on show in the solo exhibition Lines of Flight at the Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai – she reduces what appear to be necessary and eternal systems of control to more contingent and fragile artistic forms. Borders become lines, lines become drawings, drawings become art, art is a space of fabrication and fabulation.

1:7690 (2023) is a ball made up of contraband garment strips carried across the India–Bangladesh border. The combined length of the strips is proportional to the length of the border fence between the two countries in the ratio expressed in the title. The work (like others by the artist) speaks to smuggling as an act of defiance and the fragile contingency of the relationship between lines on maps and the world as it really is (the work is made up of fabric that failed to become garments).

Similarly, A0 – A5 (2014) presents pieces of handwoven cloth from Phulia on the India–Bangladeshi border, in the various standard sheet-sizes alluded to in the title of the work, each of which is marked with a line and a ratio that equates those lines, proportionally, to the fenced border between the neighbouring countries. It’s a simple enough gesture that renders the subject (the border) smaller, more fragile, more arbitrary and more human. More digestible. And hence erasable. Something that anyone can access (although, if we’re viewing it in an art gallery , we know that this isn’t the real world). While also alluding to the kind of theoretical, abstracted cartographic line-drawing that led to some of the partitions of South Asia today. Perhaps even suggesting that that was an artistic practice of sorts. In a sense, you might argue that it’s Gupta’s conscious decision to confront the world on her own terms, to bring some of its seemingly impossibly big social and political issues to the level of art, that gives her work its strength. This is not the kind of art that makes the ordinary extraordinary. It’s a type of art that weaponises the mundane.

Shilpa Gupta’s You Are the Place is on show as part of Manchester International Festival, 4–20 July; a solo exhibition of her work is on show at Galleria Continua, San Gimignano through 9 September; another solo exhibition, coinciding with the award of the Possehl Prize for International Art, is at Kunsthalle St. Annen, Lübeck from 27 September

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.