100 years on from the Surrealist Manifesto, the movement risks becoming little more than a populist attraction filled with big personalities, schisms and wacky moustaches

This month marks exactly a century since the birth of Surrealism, if we date the movement to the publication of the First Surrealist Manifesto. Or rather, Manifestoes, since there were two rival factions of surrealists back in 1924 and the first defining screed was published on 1 October by French-German poet Yvan Goll. Nevertheless, it’s André Breton’s 15 October manifesto – his first, before revisions in 1929 and 1942 – that’s considered Surrealism’s intellectual blue touchpaper. (Apparently there was a public argument between the rival demagogues, Breton came out on top and the nascent surrealists accepted his definition of the tendency.) Reading his text, I had to check that the French writer and poet wasn’t middle-aged when he wrote it (he was twenty-eight); outside of its excitement about Freud’s theories, the ‘First Manifesto of Surrealism’ is rife with world-weariness. It bemoans the stultifications of everyday life and the mainstream cultural regime of realism (Dostoyevsky catches a few strays here) and argues that the only solution is ‘the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality… into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality.’

If you somehow don’t know what happened next – sculpture, film, photography, poetry and, overwhelmingly, painting determinedly unloosed from logic and rationality while clinging to representation – today’s art museums are here to help. Surrealism’s centenary has been marked, worldwide, by blockbuster shows. There are surveys of the whole movement, spearheaded by the touring Imagine! 100 Years of International Surrealism, which showcases the usual suspects (Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte), outliers (Picasso, Francis Picabia, Giorgio de Chirico) and figures displaced by Surrealism’s baseline sexism (Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini). There are angles: go to Munich’s Lenbachhaus for a show exploring Surrealism and antifascism, Wakefield’s Hepworth for a consideration of surrealist landscapes, the Modern Art Museum of Forth Worth for Surrealism’s relationship to the African and Caribbean diasporas. Elsewhere, figures from André Masson to Leonora Carrington to Claude Cahun are getting monographic shows.

One may fairly ask, then – beyond predictable if laudable institutional canon-tweaking and focus-widening – how Surrealism stacks up a century later. And why we should care to visit, say, Yves Tanguy’s desertscapes speckled with inscrutable objects, or Paul Delvaux’s musty tableaux of women standing blankly on moonlit plazas. You might sense museum directors assuming a large public appetite for figurative painting – the most popular art medium of the last decade – and note, too, that there is a certain amount of self-consciously bizarre contemporary art that might, at a push, betray some debt to Surrealism. (Or, put another way, ‘a bit weird’ expressed in colourful paint is presently a sort of formula to sell art to dumb collectors.) The market, of course, always loves a reassessment of history, since it generates fresh inventory from less-familiar practitioners (some of whom will be indeed unfairly unknown); hence Frieze Masters, this year, spotlighting what it calls ‘marginalised’ surrealists. You can also make a lazy sociological jump to these being ‘surreal times’ or whatever, and maybe lean on Adam Curtis-like analyses of the contemporary global picture being too weirdly complicated and sense-evading for anyone to process. And then there’s the fact that the cultural history of Surrealism offers a populist attraction, filled as it is with big personalities, schisms and wacky moustaches.

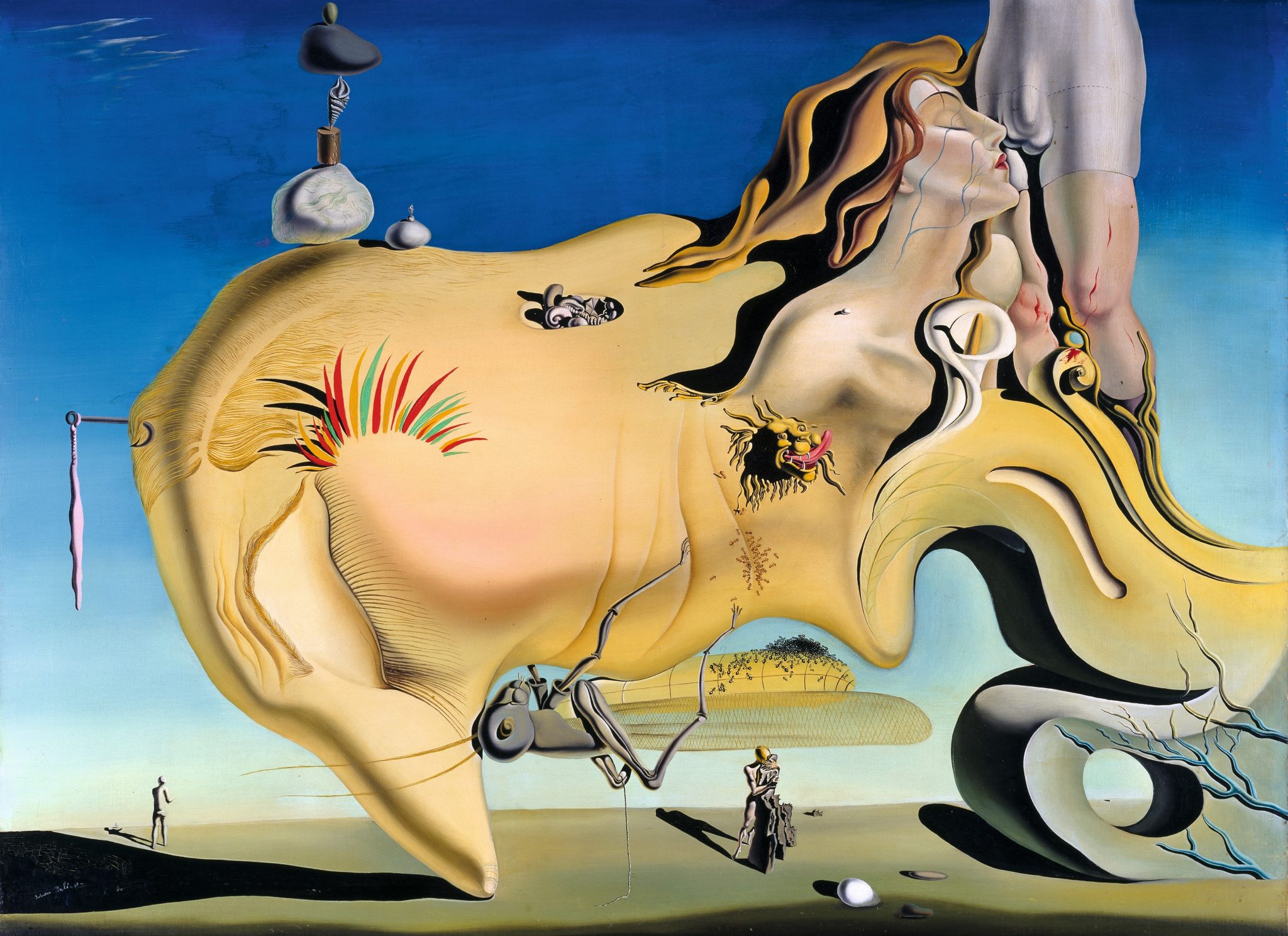

But if you’re left looking at the original work, well, most of it now looks flashily inert (or just inert). Kudos to surrealist painters for stubbornly using the most slow and static of media to try and relay the ungraspable liquid spillage of dreams. Take Dalí’, that famously precise wielder of the single-hair paintbrush to limn camembert clocks and ‘paranoiac-critical’ optical-illusion landscapes where gatherings of animals, rocks and trees compose themselves into spectral human faces. He seems in retrospect to have had a target audience of fifteen-year-old boys, and though he’s a useful gateway in this regard – reader, he got me too – he’s as embarrassing to return to as most cultural things you were formerly a teenage fan of. In retrospect, the Spaniard’s most enduring creations are his outsized persona and, relatedly, his wildly entertaining and extremely untrustworthy books, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942) and Diary of a Genius (1963). Surrealism’s other big names haven’t dated wonderfully either. Traversing many roomfuls of Magrittes at the Royal Museums in Brussels earlier this year suggested that less is, indeed, more: a little of the Belgian maestro’s bowler hats, obscured faces and steam trains thundering from fireplaces goes a long way. His later, knowingly ridiculous, grinning pear-figures benefit from not having been dulled by familiarity, and from being genuinely funny.

In any case, one thing we’re likely to be reminded of by this cavalcade of shows is that the strongest surrealist or surreal-ish visual art, from de Chirico’s stopped-time plazas to Ernst’s narrative-throttling neo-Victorian collages, and from Carrington’s human-animal colloquies to Hannah Höch’s troubled wartime landscape paintings, typically has one foot someplace else and a major disinterest in dogma or illustration. Another aspect we might usefully remember, given how the movement’s public image is dominated (the odd lobster telephone aside) by painting that often veers towards period kitsch, is that much of the best Surrealism operated through other media: ones that sync with reverie, marvelling and imagination and allow for it, and that don’t necessarily play well in art galleries.

Surrealist writing, for instance; not just the poetry but prose works like Louis Aragon’s still-dynamic, Walter Benjamin-inspiring 1926 flâneur travelogue Paris Peasant, a how-to for discovering dusty jewels in the everyday. And, most of all, the fluidity of film: via the sustained dream-logic lineage from Germaine Dulac and Luis Buñuel to Maya Deren, Raúl Ruiz to David Lynch and Charlie Kaufman and Yorgos Lanthimos, the movement’s weird heart still beats. Elsewhere, though, much Surrealism at a century or so’s distance offers, once again, the lesson you learn when you see your first Dalí in real life: it’s rather smaller than its reputation suggests.