In recent years, the act of reading tarot seems more concerned with signalling worldly social justice issues than communing with hidden forces. Was it always this way?

The one time I had my tarot read, a woman pulled the cards, looked at me ominously and declared that I had to stop anal-ysing. At first, I worried that her clairvoyance extended to my search history, until it became apparent that she was merely repeating corny self-help advice with a confusingly sexual emphasis. This was back in 2017, a time when tarot, astrology and witchcraft had become part and parcel of popular culture, at first semi-ironically and then more or less sincerely – the confluence of a loss of faith in supposedly rational belief systems and governance, advances in digital technology that led to a kind of neo-mysticism, a narcissistic fascination with the self enhanced by social media and identity politics, and the proliferation of the language of empowerment. In the artworld the occult and intersectional politics had fully merged; the work of historic figures such as Hilma Af Klint was being reappraised along spiritual lines, and it seemed like every other artist was casting spells against the patriarchy, brewing potions to ward off colonisers and organising card readings.

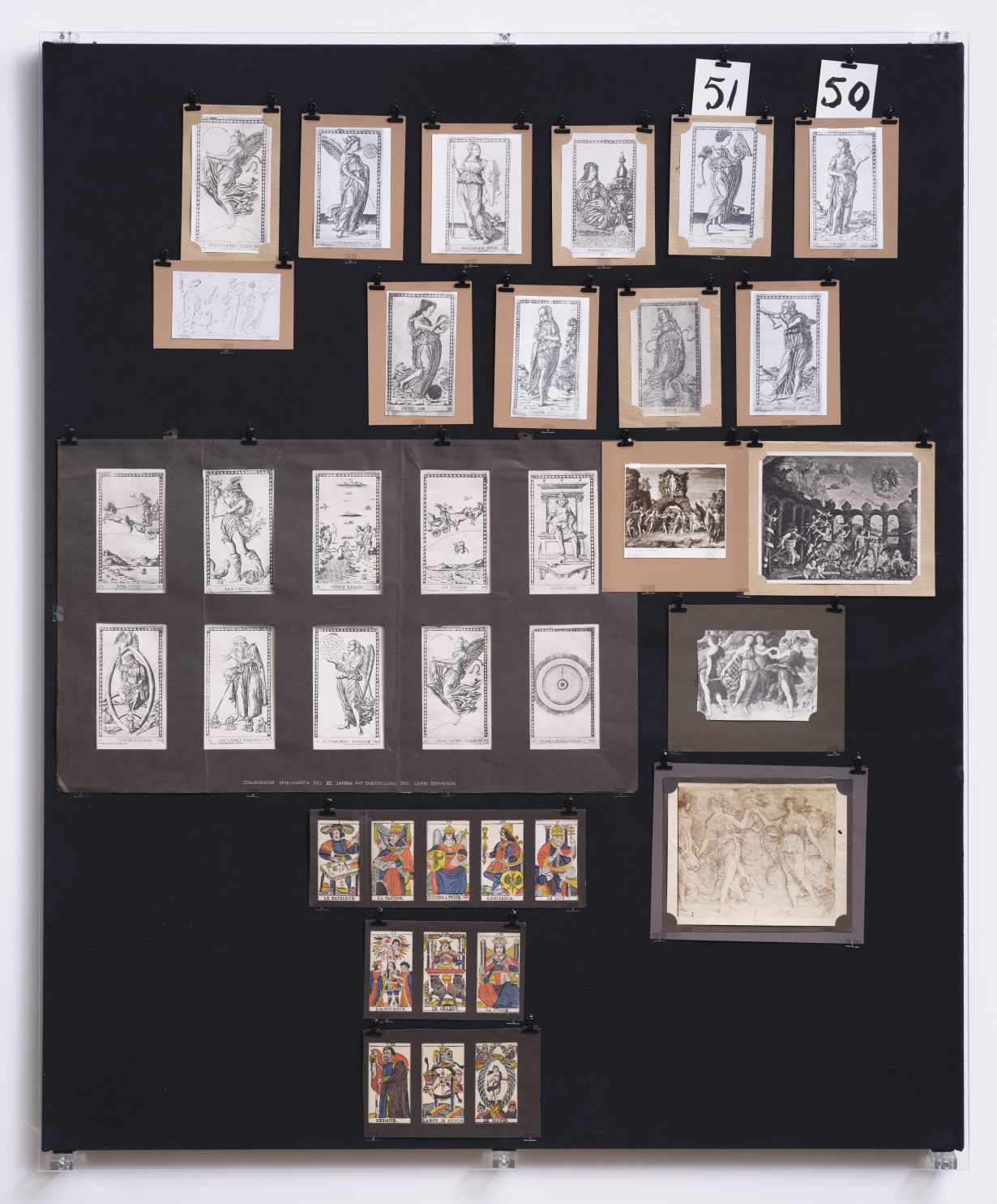

Yet tarot wasn’t always invested with magical powers, intersectional or otherwise. Its journey from Renaissance parlour game to occult medium is explored in Tarot: Origins & Afterlives, a new exhibition at the Warburg Institute in London. Tarot and card games were of particular interest to Aby Warburg. A self-taught art historian, and part of a lineage of Jewish thinkers, including Freud and Walter Benjamin, who were interested in excavating the foundations of modernity, Warburg dedicated himself to studying how archetypal images reappear across the millennia in new guises. He called this theory Nachlebe Antike, or the survival of the antique, and he attempted to chart the passage of ‘survivor’ images in the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – 68 panels of images he constructed over a two-year period in the late 1920s, shortly before his death. One panel of the Bilderatlas is dedicated to tarot, tracing the ghosts of art history as they migrate from fifteenth-century engravings of astrological figures to the illustrations on a nineteenth-century tarot deck.

In the first section of the show Warburg’s tarot panel is on display, alongside a selection of historical artefacts. Included among them are two breathtakingly beautiful tarot cards depicting a robed and crowned figure holding aloft a star (‘The Star’) and a collection of swords wrapped in a decorative scroll and surrounded by a floral motif (‘The Four of Swords’) – two cards still found in tarot decks today. Known as the Visconti-Sforza from fifteenth-century Milan (a time when tarot was a card game that had yet to acquire its spiritual significance) and believed to be the oldest known tarot cards in existence, they evoke a time of extraordinary craftmanship and splendour, when Milanese courtiers entertained themselves by playing with cards made from vellum and hand-painted in gold leaf.

It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that tarot obtained its occult associations. A French freemason named Antoine Court de Gébelin popularised the theory that the cards were a supernatural link, hidden in plain sight, to the Book of Thoth – the name given to a largely lost collection of Ancient Egyptian texts that have become the stuff of mystical legend, particularly during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries in the West, when spiritualism and fantasies of Eastern magic abounded.

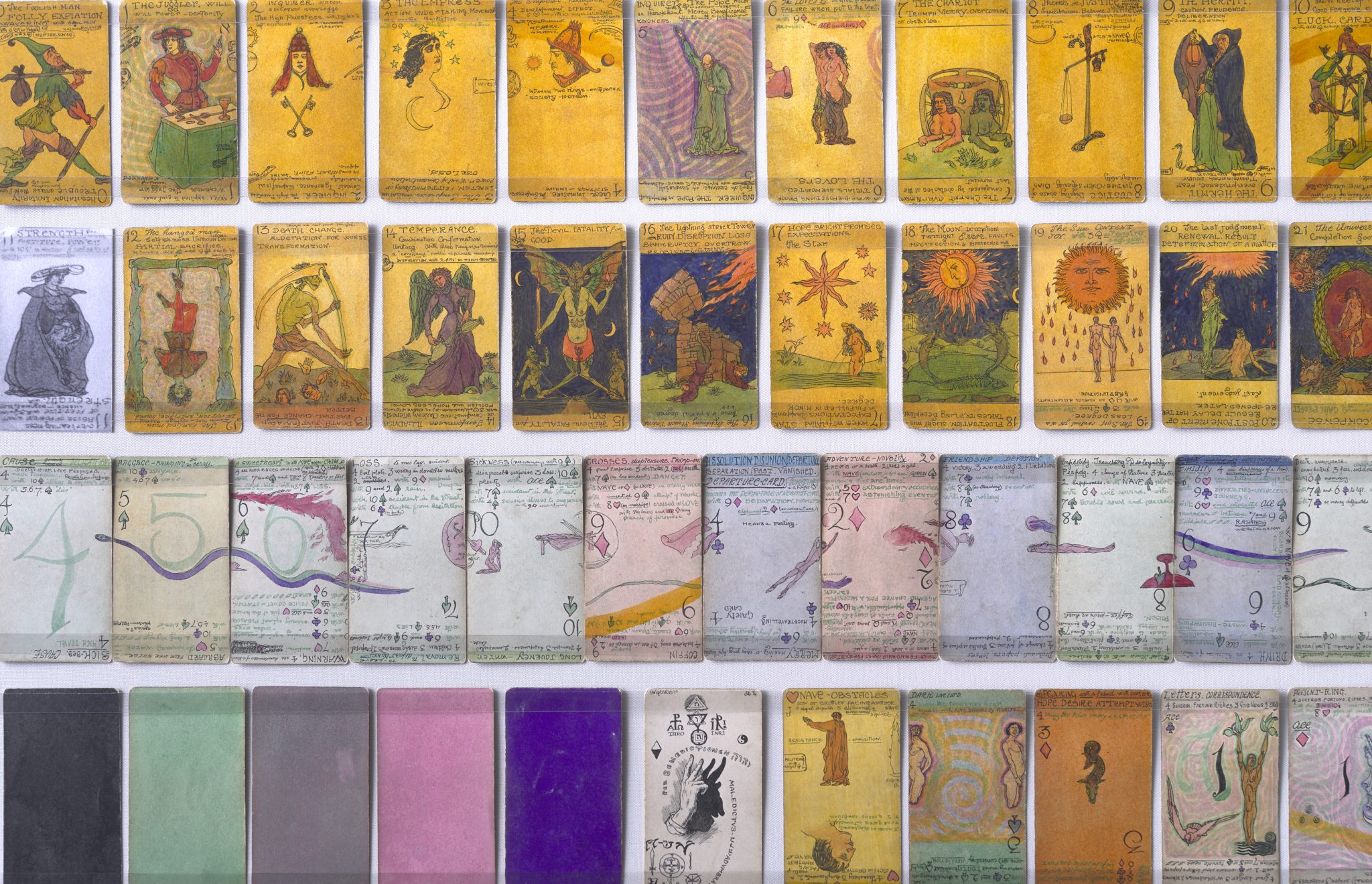

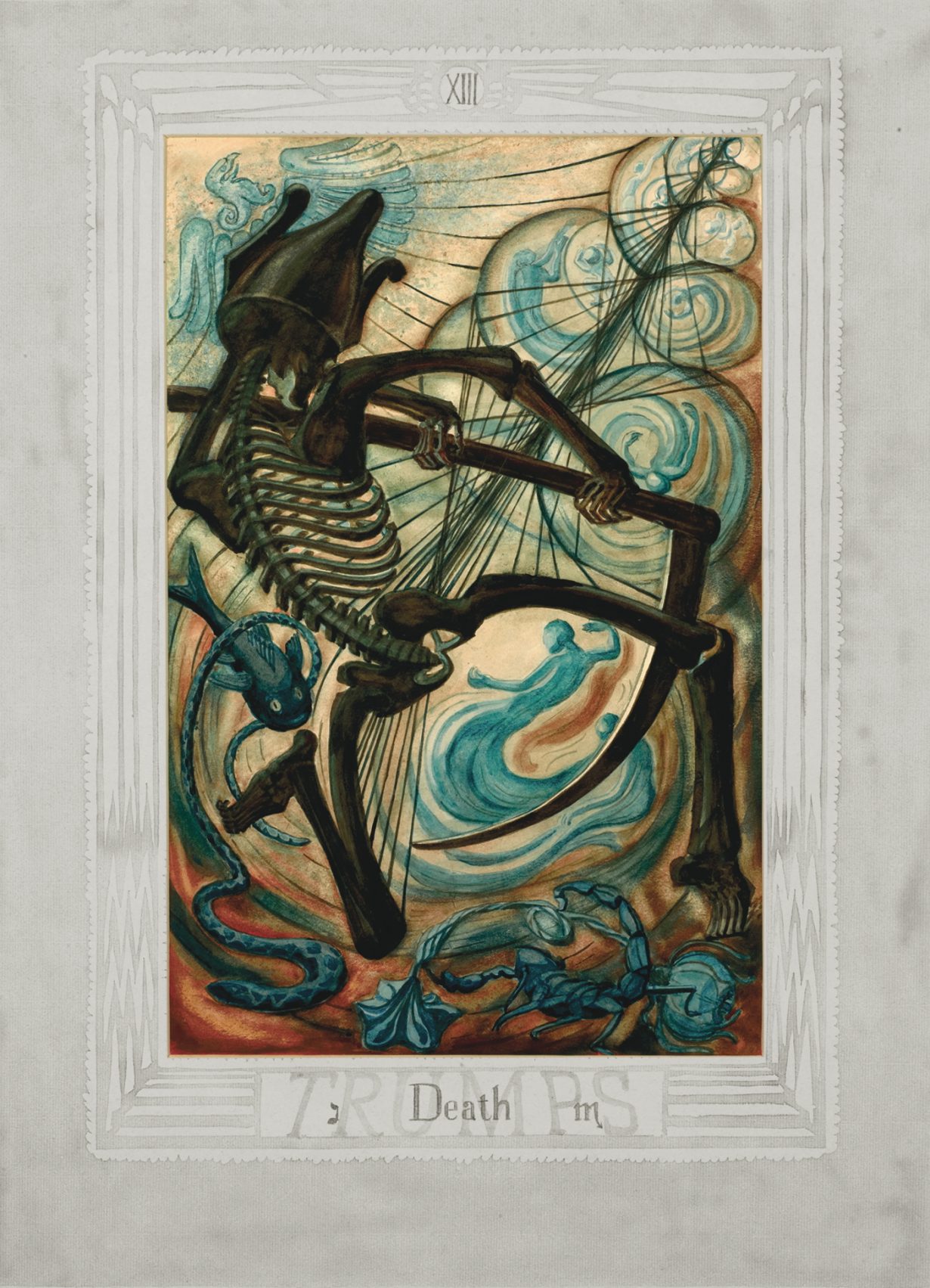

During this time occult societies began to form, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – a group whose rituals and iconography provided the underpinnings for modern-day Wicca, and influenced artists ranging from Ithell Colquhoun to Kenneth Anger – and they commissioned tarot decks for their rites and rituals. The Rider Waite deck, designed in 1909 by the British artist Pamela Colman Smith, a member of Golden Dawn, remains the best-known deck today (it was also the one used by my anal-yser). Smith’s designs are themselves believed to have been inspired by the fifteenth-century Sola Busca tarot deck. Housed in Milan and present in the show via a digital image carousel, the Sola Busca includes such images as a naked giant with pendulous breasts and a man shaking a baby over a fire, and Colman Smith gave the Renaissance grotesquery the arts-and-crafts-movement treatment. Also on display are artworks for the Thoth Tarot, a deck designed by Frieda Harris at the request of the renowned occultist Aleister Crowley during the late 1930s and early 1940s, in which the archetypes are subject to a theatrically ominous art-deco makeover.

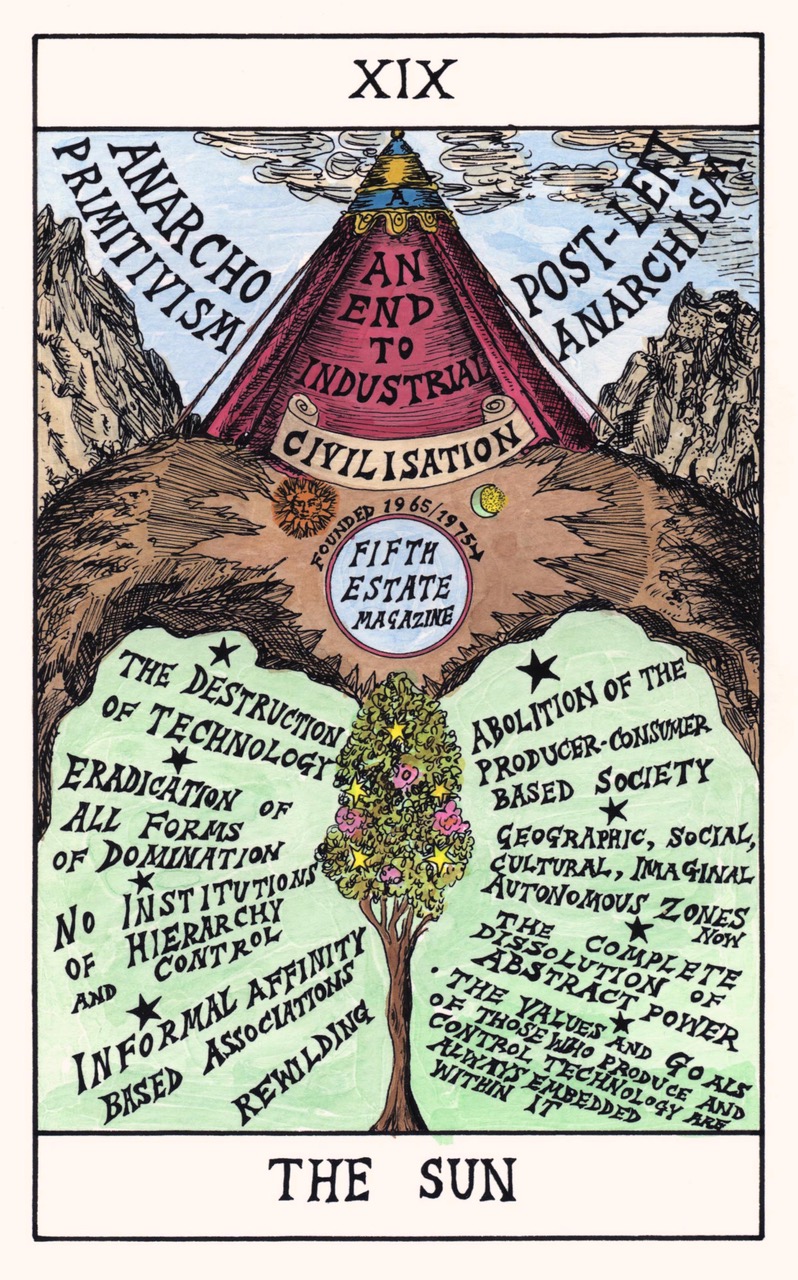

In the final parts of the show are tarot decks made by contemporary artists. Viewed alongside their predecessors they offer a sociological insight into the artistic mores of the day. In contrast to Renaissance and modern designs, which embraced the sublime and the monstrous, the contemporary examples have no such appetite for moral ambiguity. Instead, they are often concerned with representing a commitment to intersectional politics and activism, and the mystical archetypes of old emerge as real-world icons. Popular figures of left-wing academia such as Audre Lorde and Sarah Ahmed appear on cards made by the Mexican collective INVASORIX, and a deck by British artist Suzanne Treister – which includes mathematician Ava Lovelace as the Queen of Cups (a card associated with love, compassion and emotional widom) – is described as a tool ‘to envision possible alternative futures’ by drawing on grassroots movements.

These decks are typical of a contemporary tendency to view the occult through the prism of liberal academia: whether through queer theory, with its promise of transcending societal norms by establishing alternative gender archetypes, through the postcolonial interest in indigenous and non-Western knowledge repressed by European colonisers, or through the feminist reclaiming of the witch as a political identity. Interestingly, by becoming signifiers of a certain set of political and academic tenets, the decks often seem more concerned with signalling worldly social justice issues, and the political and identity-based affiliations of the artist, than transcending space and time or communing with hidden forces. Through the organisation of readings in art galleries and public spaces, it is easy to see how artists can use both the interactive nature of tarot and its blunt card-by-card archetypes to bring together people who identify with the liberal values on show – all with the added frisson of excitement, power and danger that a brush with the occult brings.

It is fittingly Warburgian that artefacts of Renaissance life should re-emerge as a source of magical knowledge a few centuries later – just as it was popularly believed during the Renaissance that ancient texts contained supernatural wisdom otherwise lost in the sands of time – and that contemporary artists should again turn to the imagery, this time as a means of expressing the political leanings of their milieu. As the exhibition and Warburg’s wider project show, art history is subject to an eternal return, produced under the apparently endless reign of a neo-classicism that was already well underway during the classical period itself, when Rome resurrected Grecian culture, which itself drew from Egypt, and so on and so forth.

Warburg called the panels of his atlas ‘ghost stories for adults’. Watching the ghosts move between surfaces and across the centuries is an encouragement to look beyond the significance we attach to imagery in the present, and to take a longer view. For the power of images is far more otherworldly, and far more profound, than any temporary associations tethered to a deck of cards. This is where the true magic of tarot, and indeed art history, lies – in the staying power of images, and their ability to survive epochal dogmas and fashions and emerge again, and again, and again.

Rosanna McLaughlin is a writer and editor based in East Sussex. Her latest book is Sinkhole: Three Crimes (Montez Press, 2022)