From love letters to mail-order pornography – on the long history of LGBT communities finding solace in the anonymity of the postal system

‘Come back, I must see you at once.’ So telegrams the heroine of The Well of Loneliness to her lover, Angela, who is holidaying with her husband. Written in 1928 by Radclyffe Hall, the novel exposes society’s prejudice towards gay relations. The text itself raises suspicions at the village post office in rural Worcestershire from which it is being sent. ‘The clerk counted the words with the stump of a pencil, then she looked at Stephen rather strangely.’ For Stephen – the name an affectation of the protagonist’s late father, who had been expecting a boy – the urgency in the request comes from the fear that she is losing the affection of a sweetheart. Had she been in a mood to tread carefully, she might have used the more private, but slower, postal system.

In 1840 the Royal Mail introduced the Uniform Penny Post, a reform that allowed anyone to post a letter from one location to another within the UK for the cost of a penny. It was a hugely democratising moment, making mailed correspondence available to great swathes of the population for the first time. It also allowed for far greater privacy, a factor that raised hackles with conservatives of the time, who feared it would permit the kind of illicit relations that entangled Stephen and Angela. Today of course email and social media have superseded the letter (not to mention the telegram), leaving the economic viability of postal services under threat. In the UK Royal Mail share prices have plummeted since the company was privatised in 2013, and in the US the Postal Service has become yet another enemy to be squashed by Donald Trump, collateral damage in the president’s ongoing battle with Amazon.

With the potential loss of these services no doubt in mind, Queer Correspondence, a new project from Cell Project Space in London, recalls the long history of LGBT communities finding solace in the anonymity of the postal system, be it for writing letters to lovers, receiving mail-order pornography without the danger and embarrassment of entering a sex shop or, in the context of art, participating in the niche tradition of queer mail-art. The project entails various artists and writers (all of whom had been originally commissioned to make work for the gallery’s East London venue, but whose shows were cancelled due to the COVID-19 lockdown) creating work through mailed correspondence between their ‘queer families’ – the LGBT communities in which they socialise and work. These collaborative projects will then be produced in an edition of 500 and mailed out to anyone who wishes to receive them (and who has signed up via the gallery website). The first commission, the result of communiqués between artists Alex Margo Arden and Caspar Heinemann, each self-isolating, was delivered to letterboxes in June; in July the pen pals are Los Angeles-based Salvadoran artist Beatriz Cortez and Korean Kang Seung Lee, also living in LA; and so on, with a new commission ready each month until the end of the year.

Although initiated in response to the pandemic, Queer Correspondence is also an addendum to the official history of mail art that traces its lineage from the postcards Marcel Duchamp sent a neighbour in the early twentieth century, to the collages and prints Ray Johnson posted to friends during the 1950s, inspiring what later became known as the New York Correspondence School, and on to various 1960s Fluxus artists and On Kawara. The medium has a political history as well as a conceptual lineage, linked to pamphleteering and the production of samizdat from, among other places, behind the Iron Curtain, China and Southeast Asia. Moreover, the relative privacy afforded by the postal service offered a way around censorship systems imposed by oppressive regimes: mail art became hugely popular in Latin America for artists surviving the various military dictatorships, for example. The works mailed out through Queer Correspondence will come with a stamp designed by Gelare Khoshgozaran, an artist who has used postal art previously to explore American authoritarianism. In her 2016 project U. S. Customs Demands to Know (2016–), the Tehran-born, LA-based artist sent parcels packed with LEDs, a luminescent glow visible through the packaging, by post from Iran to the US in the face of international sanctions (and no doubt the suspicion of border staff).

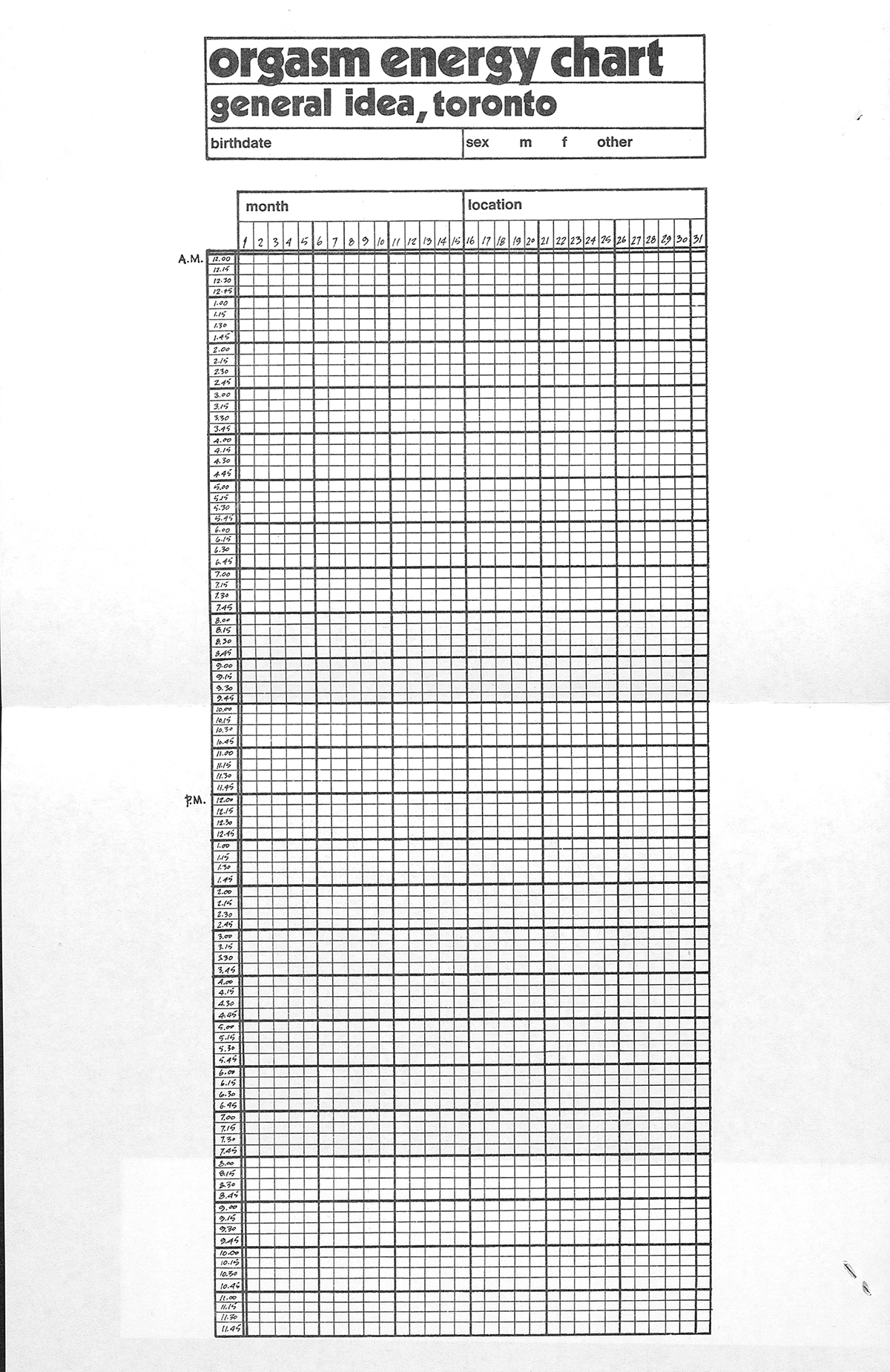

General Idea (A Project of AA Bronson), Orgasm Energy Chart, 1970, offset on bond paper, 43 × 28 cm. Courtesy the Estate of General Idea and Esther Schipper, Berlin

In the US, however, an alternative history can be charted in which the medium served as a way for renegade individuals or disparate avant-garde gay scenes across the country to hook up. The late-nineteenth-century Comstock laws forbidding the posting of anything deemed obscene or sexual in nature (which would come to include sex toys, contraceptives and literature on abortion) lost force over time, many reshaped or simply repealed during the 1960s to allow the unhindered transit of missives containing queer subject matter (and, in some cases, downright ‘filth’).

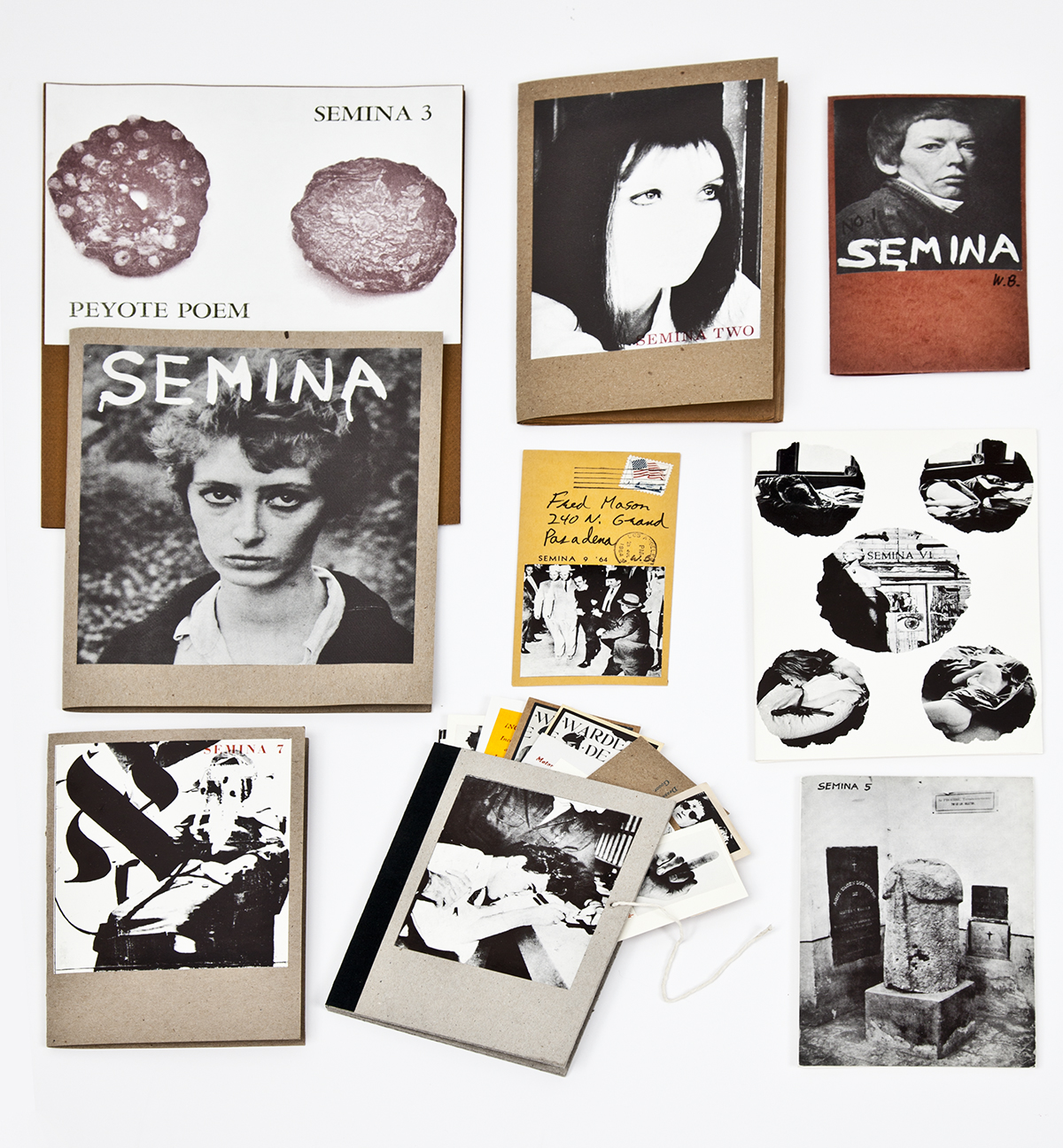

This moralising retained more of its legal force during the 1950s, however, when Wallace Berman gained a following in the LA underground scene. Berman liked jazz, drugs and the occult, and surrounded himself with a gang of similarly far-out brethren for whom sexuality and gender were slippery concepts. In 1957 he had an exhibition at the Ferus Gallery that earned him the attention of the LAPD, who arrested him for showing lewd material: the evidence, a work titled Factum Fidei (1956–57), featured a close-cropped picture of a couple having graphic sex that had been framed and hung from a large wooden crucifix by a short rusty chain. Interestingly, the photograph, which was by a friend named Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel, an Aleister Crowley-acolyte who went by the mononym Cemeron, had originally been contributed with no trouble to Semina, Berman’s loose-leaf magazine (nine volumes of which were published between 1955 and 1964) featuring cut-up poetry and collage sent in by the likes of Charles Bukowski, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Jean Cocteau. Written under the pseudonym Pantale Xantos, one poem by Berman reads, ‘A face raped by innumerable messiahs places into sodden cotton an anxious needle / A face hisses rules to cathedrals and prepares for the narco myth.’ The cover of issue five features a large stone penis; issue six a naked woman with a revolver. Distributed to a limited audience via mail, it operated away from the prying eyes of the vice squad.

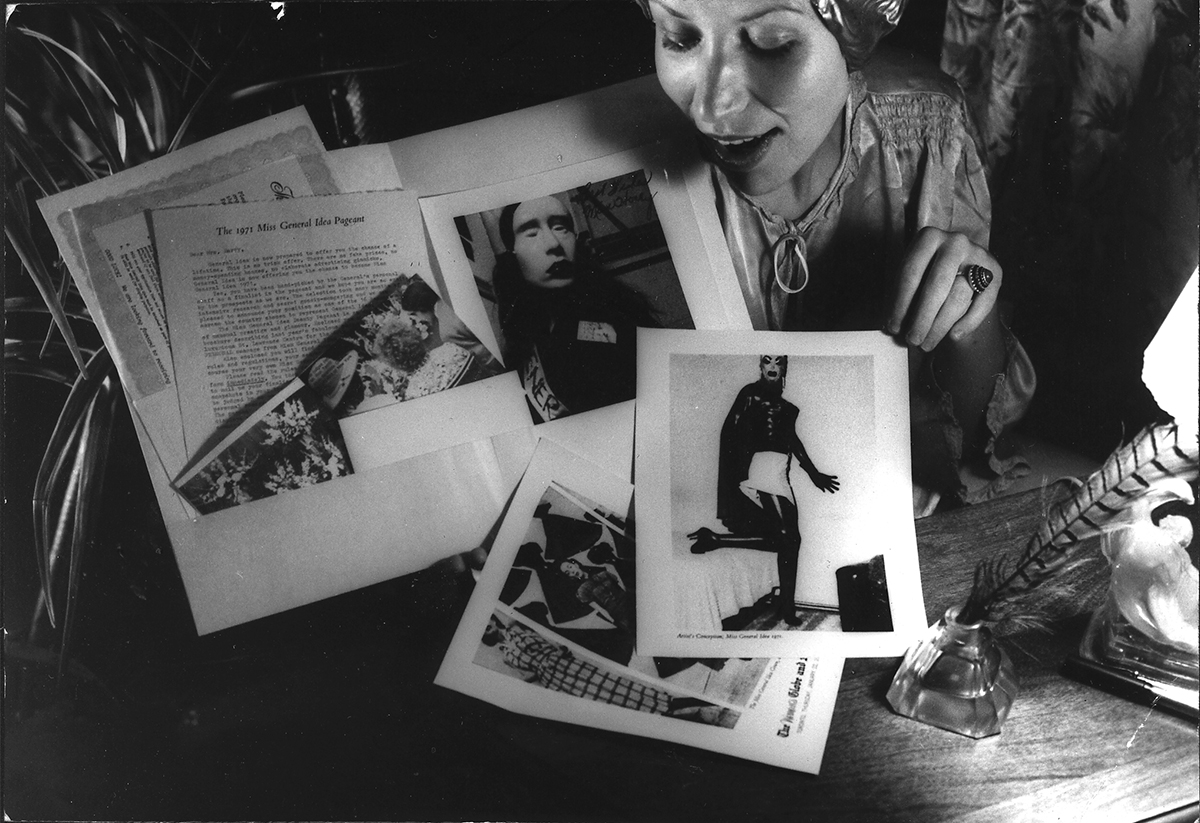

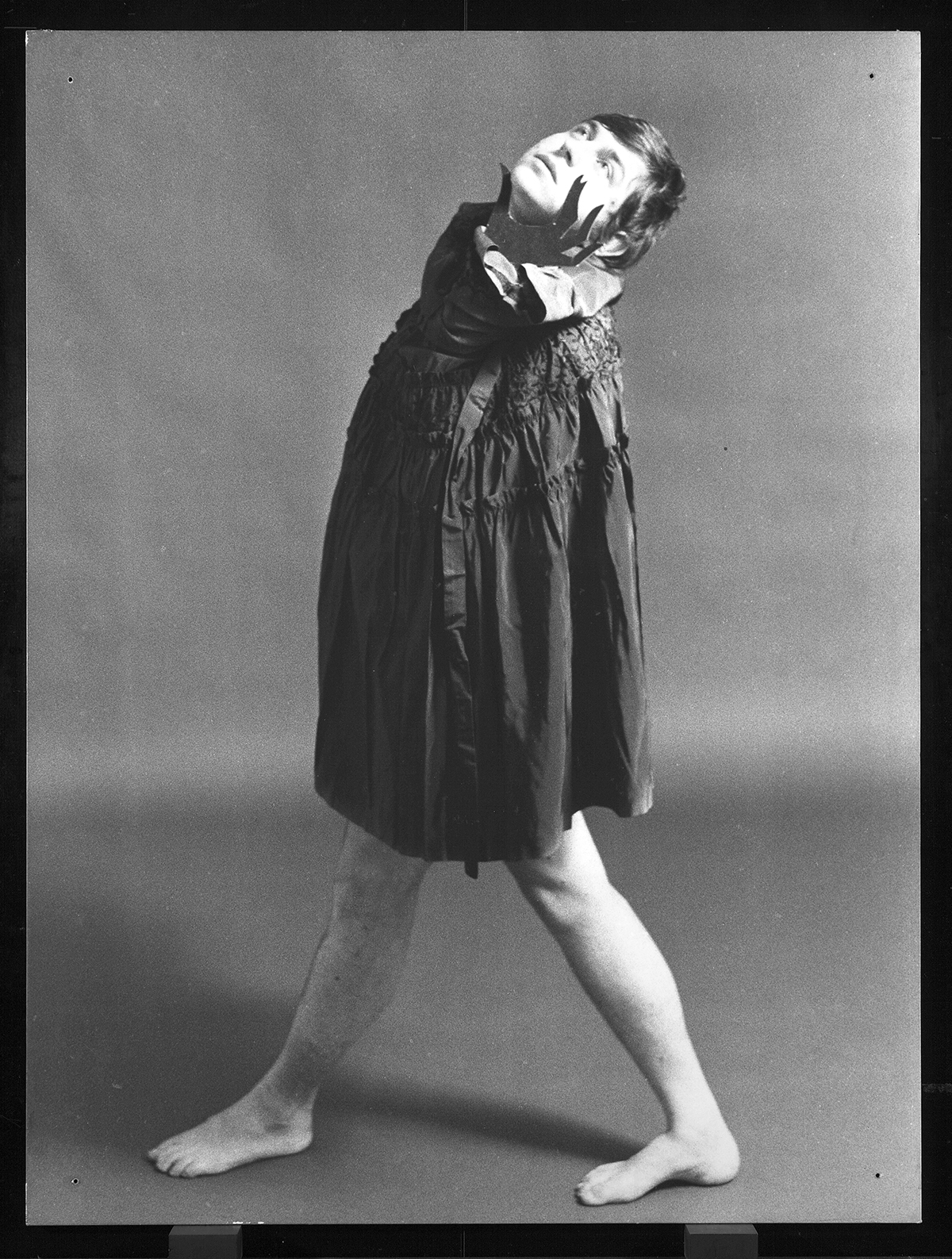

General Idea, The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant Documentation, 1971, winner Marcel Dot, Gelatin silver print, 25 x 20 cm Photo: Vincent Trasov. Courtesy the Estate of General Idea and Esther Schipper, Berlin

Berman’s project was not explicitly gay – the sex scene in Factum Fidei is a straight one, though there was an element of gender nonconformity in a lot of the contributions to Semina – but provided an example of how to distribute art that would have been deemed unacceptable either by the law or the established art system. The post office became a place of rescue for misfits and nonconformists. The Chicano artist Gronk recalls that he grew up in conservative surroundings and was ostracised for his perceived difference at school. By the time he moved to LA, in 1972, and met the mail-artist Wiz Dreva (the pseudonym of the late Carlos Almaraz) at a lecture given by Willoughby Sharp, the founder of Avalanche magazine, he was also beginning to experiment with postal art. Gronk recalls Almaraz as being ‘very, very cocky’ with the speaker, and afterwards the two got talking. They exchanged addresses and promised to write. While no artworks came for a while (Dreva would claim he smudged the ink with which Gronk had written his address by masturbating on the scrap of paper), they met for a second time at a gig and started to exchange a series of Dada-inspired collaged postcards and long, fantasy-filled letters.

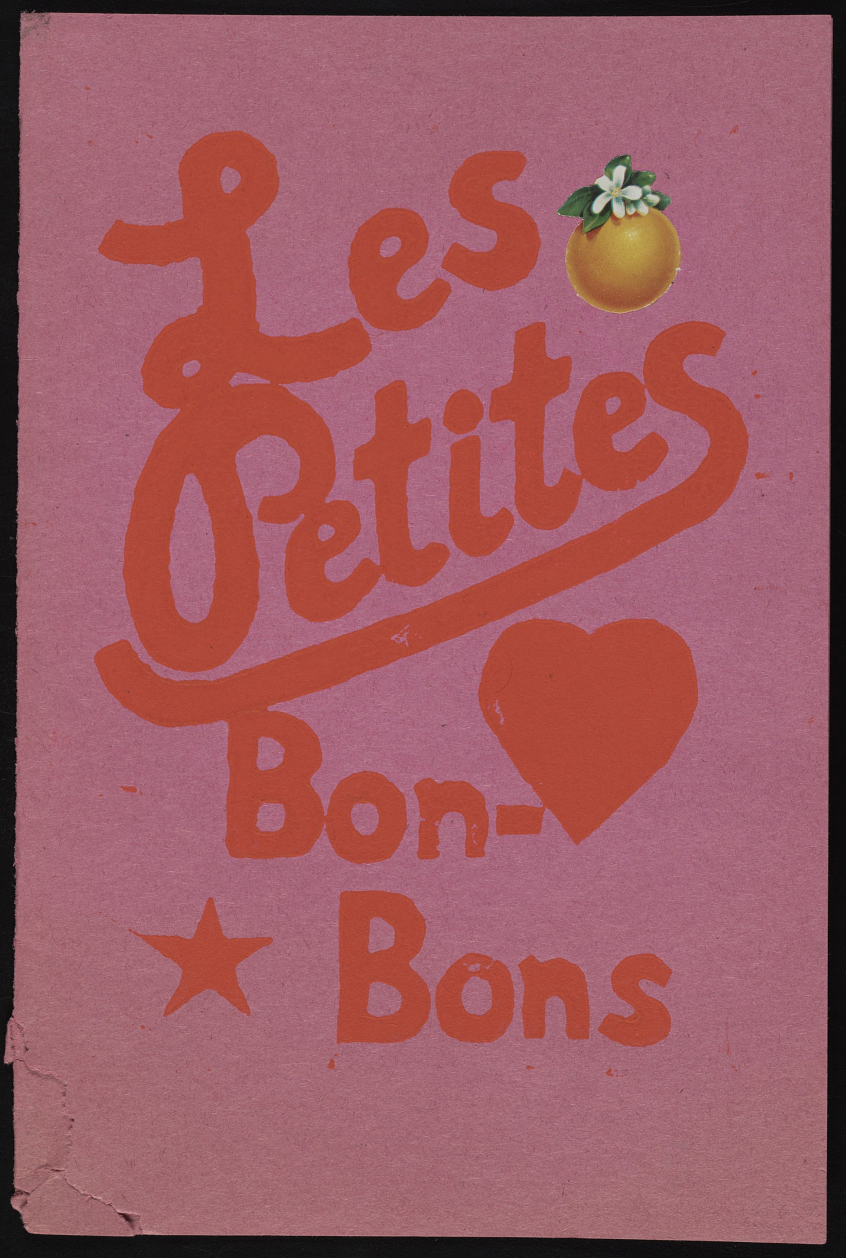

The correspondence bore fruit both personally – Dreva recalls it was Gronk who took him out on LA’s gay scene for the first time – and professionally. By 1978 Dreva/Gronk had ten years’ worth of the paraphernalia to exhibit at LACE, in just the second show the LA nonprofit staged. Separately Dreva was the lead figure in a group who called themselves Les Petites Bon-Bons, active in both mail-art circles (including exchanges with Johnson, General Idea and the British COUM collective) and the local glitter-rock scene. It is this joining of local cliques and global networks that proved a driving force for queer mail-art. The activist and critic (and cofounder of Printed Matter, Inc) Lucy Lippard received mail from the group, including one missive that featured their name fashioned in red script alongside a black-and-white photo of the group embracing. It is captioned ‘imagine a Gay universe’. A second provides a manifesto of sorts: ‘Les Petites Bonbons are Gay Pansensualists. We acknowledge and we reject the attempts of straight male sexuality, thru genital imperialism and heterosexual male supremacy, to limit and restrict human experience.’

Courtesy the Estate of Wallace Berman and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles

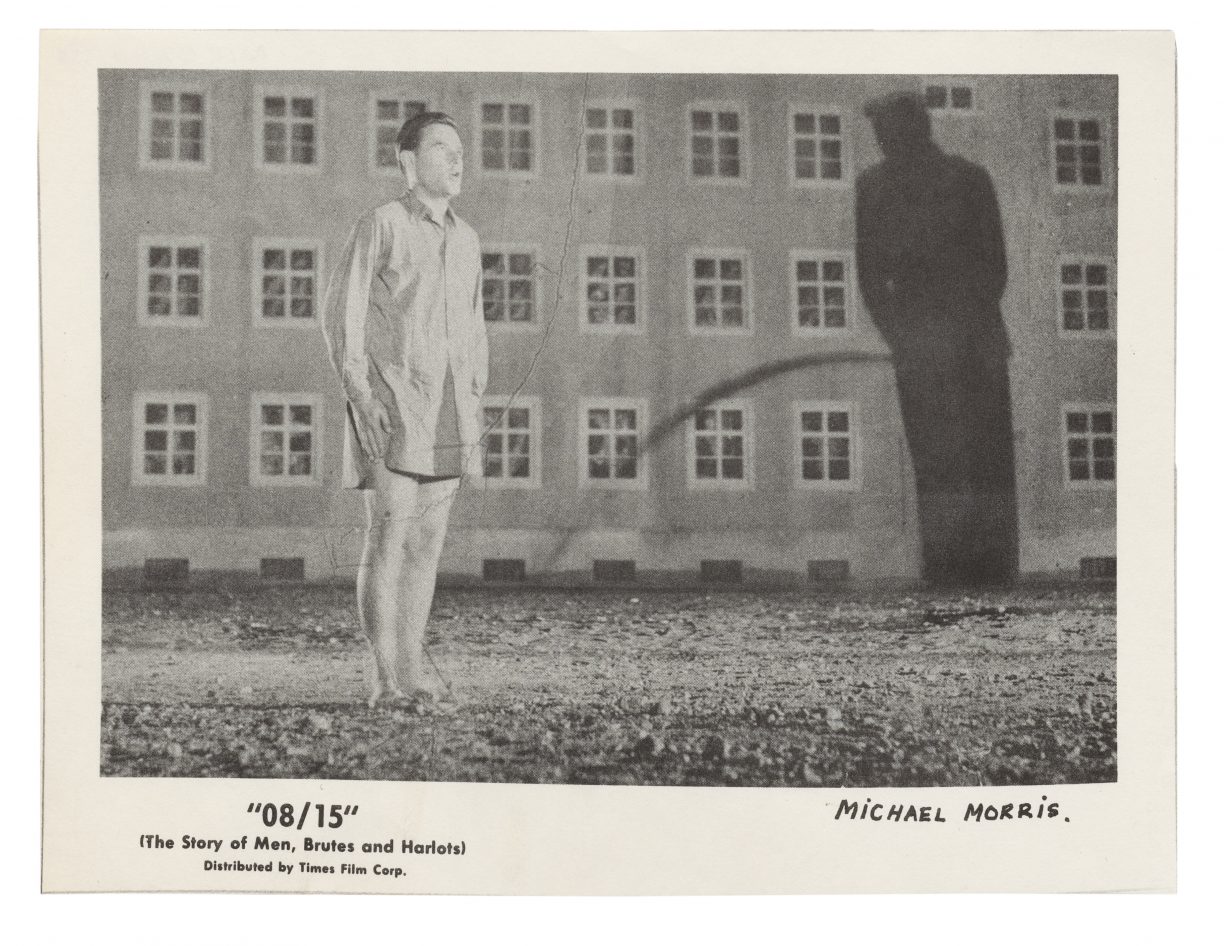

General Idea similarly used the post to facilitate their art and activism. Throughout the 1970s almost all of their projects contained an element of mail art. Some – like the Orgasm Energy Chart (1970), in which numerous collaborators were asked to log their orgasms over a month on graph paper and return it to the group, the results a seemingly empirical study of sexual liberation – use mail art as a medium in its own right. Even one of the trio’s most famous works of the period, the gender-bending The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant, entailed the group mailing out kits to over a dozen artists, each containing the rules and regulations for their alternative pageant, together with a ‘pageant gown’ in which respondents were asked to pose and then mail back in the form of a photograph. These posted performances were then judged and awarded at an intentionally over-the-top prizegiving ceremony held at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. The project carries all the hallmarks of General Idea’s interests: fetish, ritual, libidinous imagery and consumer culture. Interests shared around the same time by fellow mail-art protagonists the Vancouver-based Image Bank: the two groups collaborated on occasion. Also a trio, Michael Morris, originally from the UK, and Canadians Vincent Trasov and Gary Lee-Nova took their collective’s name from William S. Burroughs’s cut-up-technique novel Nova Express (1964), in which the Beat writer meditates on and rails against various systems of control. In it, society, culture and government are represented by viruses that attack the body and co-opt it for their own gain.

For Image Bank, and their peers within the interconnecting networks of queer mail-art, the use of the postal system was a way of hijacking a corporate or governmental authority for nefarious and radical means. The return to mail art in 2020 might seem mere nostalgia for a time when such utopian ideals seemed obtainable – the medium all but replaced by the internet – but Cell Project Space’s Queer Correspondence project also taps into the queer fear of isolation; and a fear of the historic loneliness often felt by LGBT people prior to our hypernetworked age and the era of social media. In a period of being confined to home, unable to feel the warmth of human connection, a letter, it seems, still goes a long way.

Queer Correspondence runs through December, via Cell Project Space’s website