Cruella is Hollywood’s latest diagnosis of wickedness via pop-psychology tropes – but our desire for monster-redemption stories often ignores a difficult truth about ourselves

What makes a person plot to kidnap 99 Dalmatian puppies with the intent to kill, skin and then wear them? Could it be that, when such a person was a child, a pack of blood-thirsty Dalmatians chased her mother off a cliff as she argued with a mysterious stranger?

Maybe that alone wouldn’t quite be enough. So, let’s say that child grew up and managed to find her way into a low-level job in fashion. She works all hours of the day and night for a frosty, stern designer known as ‘the Baroness’, who takes credit for her junior employee’s work. And then, our orphan discovers that the Baroness is in fact the mysterious stranger from all those years ago, and that she unleashed the spotted hounds on her mother (using a kind of magic whistle, of course). Still – maybe this wouldn’t quite be traumatic enough. And, besides, would you really hold the dogs responsible? After all, they were only following orders.

But then let’s say it turned out the Baroness was a crazed narcissist, and was actually this person’s real mother all along. And that she had secretly tried to kill her own infant child. This might screw you up. Murderous impulses might run in the family, which could explain the urge to kidnap Dalmatians.

This is the gist of Cruella (2021), the origin story for the camp, puppy-napping Disney villain. It offers not so much a coherent explanation of Cruella’s motivations and psyche, as a lot of disparate pieces which could kind of fit together to make one. If you squint. We have family trauma, orphanhood, a psychological disorder of some sort (or at least a wicked personality), and precarious working and living conditions. Lots of boxes have been haphazardly ticked. Cruella hasn’t really been explained, exactly, but it is clear we are meant to think of her as sympathetic.

Cruella is the latest example of a trend for villain backstories, in which characters previously cast as caricatures of wickedness have their monster-hood (sort of) explained via pop-psychology tropes and references to societal ills (a vague anti-patriarchy strand runs through Cruella). In recent years we have also seen The Joker (2019) and Maleficent (2014) (and even, already, a Maleficent sequel, Maleficent: Mistress of Evil, 2019). Of course Hollywood is fucked up and derivative now because of IP, Netflix and lots of other reasons of which we are all vaguely aware (but that I don’t have space to go into here) and it is tempting to see these films as just another example of the Marvel-universification of entertainment. But our interest in the villain origin story is not just a Hollywood thing.

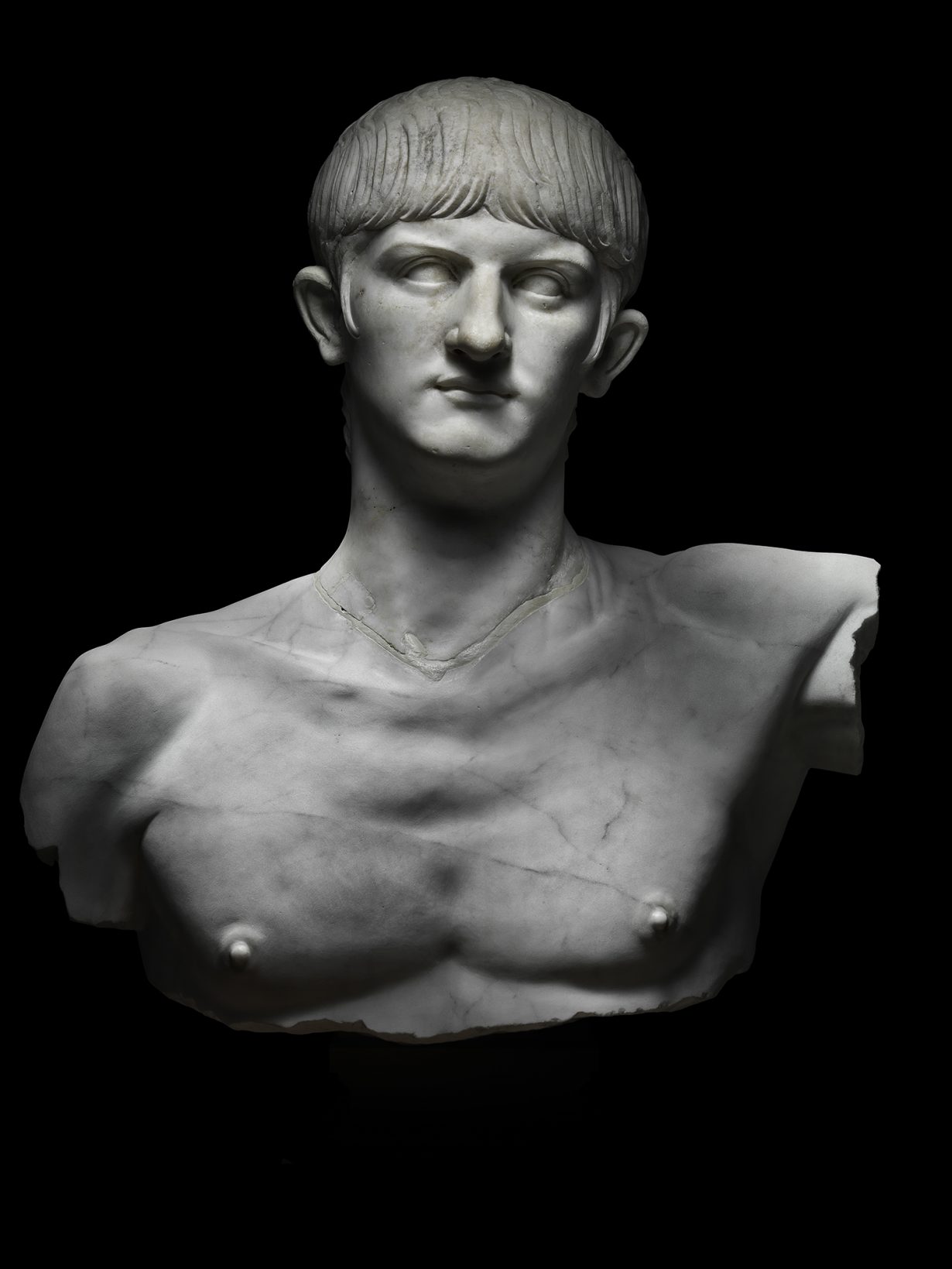

permission of the Ministero della Cultura; Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari. Courtesy British Museum, London

Even the Roman Emperor Nero has been given a similar treatment in a recently opened British Museum exhibition, The Man Behind the Myth. A brilliant line from the show’s promotional text reads: ‘Was he a young, inexperienced ruler trying his best in a divided society, or the merciless, matricidal megalomaniac history has painted him to be?’ The answer is probably both, but the inference is that ‘Nero as megalomaniac’ can be explained by ‘Nero is inexperienced and stressed as a result of the responsibilities thrust upon him’ and I wonder if this is true, and why we have started explaining monster-hood in this way.

We all seem to be very concerned with each other’s morality these days. The puritanism of online spaces, where a culture of surveillance, projection and public denunciations is widespread, has worsened during the pandemic. And, as more of life has been conducted online over the past 18 months, this has felt like more of a feature of the ‘real world’. We seem to be searching, constantly, for proof that other people have done bad things so we can demand apologies, explanations and self-flagellation. But, in my view, the more we condemn badness in others, the less comfortable we are about acknowledging it in ourselves; the appeal of the scapegoat is that it offers us a superficial form of redemption, with no need for self-examination or atonement on our part.

The appeal of these redemptive backstories to me seems similar. They too offer us a refuge from accepting our worst selves. By rationalizing monsters as the product of bad childhoods, society, stress or narcissism I feel that we ignore a truth that can be hard to accept: that our own worst impulses are often completely irrational.

What makes a person lie? Steal? Try to ruin the career of a perceived work rival? Call your manager? Steal your boyfriend? Gaslight you and then ghost you? Kill someone? Cheat on you? Run away and leave their children to be brought up by a struggling single mother? Spit in your food? Sexually harass a colleague? Be a matricidal megalomaniac of historic proportions? Break lockdown rules? Own a private jet? Terrorise Gotham and obsessively stalk Batman? Be mean about you behind your back? Litter or urinate in the street? Kidnap a child? Not wear a mask in the supermarket? Commit a terrorist attack? Lie to the police? Plot to kidnap a litter of Dalmatians?

Some potential reasons: bad mothers; absent fathers; personal trauma that has never been resolved because therapy is too hard to access; poverty; addiction issues; an unbearably hot day that fosters the overwhelming sense that no action is of any real consequence; selfishness; not doing the work; capitalism; feeling lost and directionless because life these days revolves too much around the computer and not enough around nature; being born too rich and spoiled; the pressure of being a young, inexperienced ruler trying his best to lead a divided society; society; a sense of entitlement; a sense of superiority; a sense of victimhood; because nobody was brave enough to ‘hold the offender accountable’ on the internet; watching a family member be pushed over a cliff by a pack of Dalmatians.

Maybe one of these things, or a combination of them, would be a good explanation, but then again, maybe not. We can be bad, any of us, for no good reason.