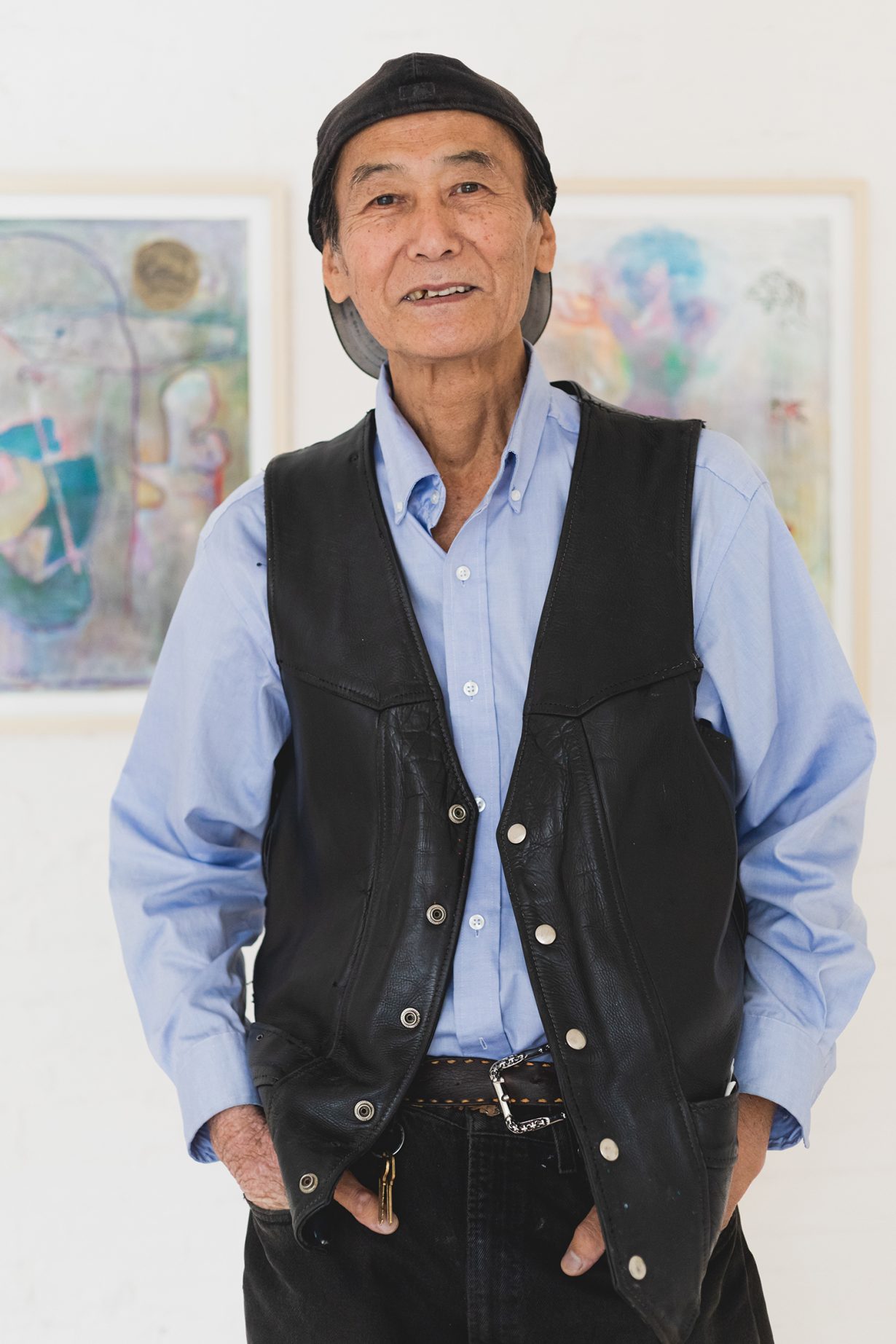

“Some people think about being a doctor, but I still think about being a fine artist”: the 76-year-old artist – whose paintings dabble in surrealism, abstraction and postmodern playfulness – spies his chance

E’wao Kagoshima, who goes by ‘Rocky’, was born in Japan in 1945 and has lived in New York since the mid-1970s. He exhibited his paintings frequently during the 80s, sometimes at significant institutions such as London’s ICA or New York’s New Museum, and sometimes as a part of the community of artists in the East Village.

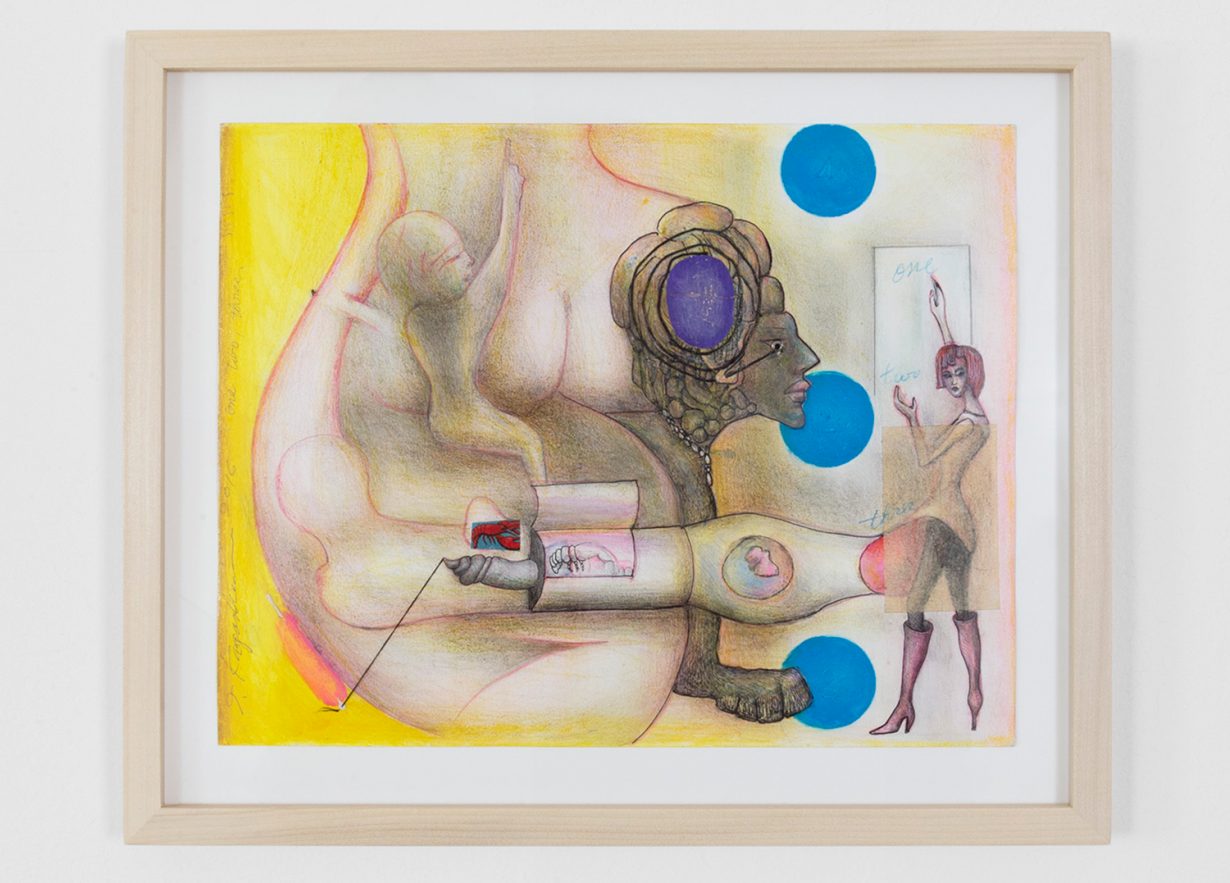

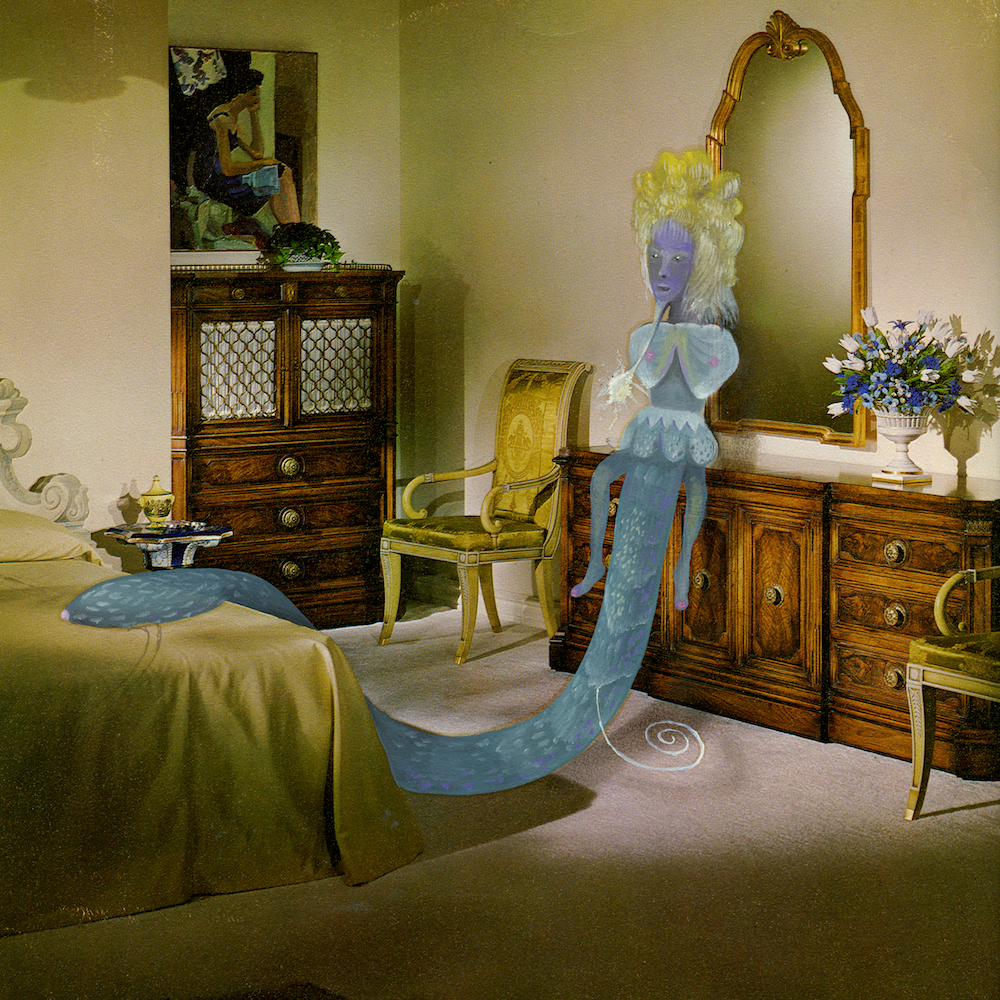

After his early period of visibility, however, he stepped away from the artworld and showed very little for the following two decades. He was, nevertheless, painting during this period, and in the years since, he has exhibited work from across the entire span of his career. His paintings have been referred to as surrealist, and some of the work clearly relates to that tradition – dreamy scenarios, refined draughtsmanship, impossible narratives – but like Paul Klee, who also received that descriptor, Kagoshima has a willingness to explore beyond his foundational style, in his case into both abstraction and postmodern playfulness.

The details of his autobiography are hard to pin down, and in our conversation, when I asked him about particularities, he seemed unable to confirm any of them, either because he doesn’t remember or he prefers not to. By his own account, Kagoshima never experienced the kind of success that could sustain him financially, a situation that continues to plague him even now at the age of seventy-six.

At the time we spoke, he was included in MoMA PS1’s Greater New York, which is for him one of the most significant moments in his career. We conversed through Zoom, with the assistance of the show’s curator Ruba Katrib, who has worked closely with Kagoshima over the last few years. During our talk she served as a kind of moderator, guiding us through what I soon learned was Kagoshima’s first online video conversation, and one of the only interviews he has ever done. Kagoshima’s thick accent, along with the internet static and muffling facemask, made much of the conversation difficult to parse as I listened to it afterward. What follows is the material I was able to excavate with confidence.

Ross Simonini Your work ignites some of my childhood wonder. How would you describe your childhood?

E’wao Kagoshima I didn’t like school. I wanted to go through the bushes and trees and be near animals. Swimming in the river. I was not interested in the city. But later, after high school, I liked the city life.

RS Do you still think about childhood?

EK Not much. Getting older, I lose interest in my past. I am still getting to what my dream is. I stick to my dream. I don’t compare myself to other people but I always want to be more intelligent than what I am. This is why I started reading. I went to bookstores to get art books and I went to galleries. Because I didn’t speak English I wanted to understand art more. I wanted to know the New York art scene. I am ambitious. I can do more, you know, and I still have a dream and I’m not satisfied. People think when you are young you are ambitious, but I am old and ambitious. Some people think about being a doctor, but I still think about being a fine artist.

RS Have you always been that way?

EK I have to make money, my own money, in life, and I cannot do this with art. But I want to stick with art. I remember when something inside of me changed and I became a hungry guy. I’m primitive now. I need food. This is my situation, every day. Physically, when I was young, it was easy, but getting older might not be so easy to be an artist. I want to live longer so I can do this. If I see something hopeful, I want to live longer. So now I stick with PS1. I stay here.

RS Working there?

EK Yes, I am now in [MoMA PS1’s quintennial survey of significant NY-based artists] Greater New York. There are 47 artists in the show. This is just like the 47 samurai story, the most famous story from Japan. There are 47 samurai who live in a castle in Tokyo and they want to take revenge on the lord of the castle.

Ruba Katrib Rocky, is this a metaphor for the artworld?

EK No. Forty-seven artists. Just like the famous story.

RS Is it true that you sold artwork on the street?

EK I am a practical guy. I need strategy. Like a company, the most successful artists in the United States have strategy. It’s just business, even though most artists believe they are next to God. But if someone pays me $1,000, I will make them work. I am not a rich artist. I come from Japan. I don’t want to be wealthy. I want to survive. In 1983 I had a show at the New Museum. I had a few collectors. One of them had a museum and he was the only one who stuck with me. But most rich people are very…

RK Fickle? [laughs]

EK …And I know Ruba because of a group show at SculptureCenter. You need to be connected. Otherwise you get no attention. I am at MoMA now, so I get attention. Maybe this is the last chance… Or no! It’s my beginning! But it is also my last chance. Last weekend I looked in The New York Times and there was my name, E’wao Kagoshima, right in the centre [slaps his hands against his leg]. But no one has heard of me still. But this show will be open for six months, which is very unusual, and it only happens every five years. So the next few years might be something. It’s like the 47 samurai story. Who will kill the lord?

RK Who will kill the lord? [laughs]

EK Yes. I hope this show will bring many people, but the artworld is always changing and my painting is always changing. I’m only one of 47. I am not a big artist. But my chance is here.

RS You often show work from very different time periods during your career. Do you see all your work as connected? Or has it changed over the years?

EK Look at Picasso. The most powerful creator in history. He was always changing. Having no style is important. But inside no-style is an invisible idea that is difficult to recognise. So, me, why I am changing? If I could do one style that would support my living, I would focus on that style. But I cannot find that. I can’t live on what I make. So I change. So this MoMA show is a programmatic idea of what I am going to do now. In ten years I may be in the ground somewhere. If I were young I would not feel hurried. But this is my last opportunity to do something. Today I feel good, though tomorrow I might be in a rush. Last night I worried that I cannot talk like a philosopher or an NYU professor for this interview, because my English cannot be expressed. My English is only as good as “Give me money!” Today, a man asks me, “Give me money!” on the street. So I said to him, “Do I look like a rich guy?” He says, “Give me money!” But I only have hundreds of dollars in the bank.

RK Maybe it was because you are wearing your nice button-up shirt.

EK Greater New York! I found my name in The New York Times, in the centre. Unfortunately, my picture was not there.

RS Do you –

EK And this is why I don’t want to talk about art, because my art is for eyes only. My mouth is like an advertiser. “My work is great, you know? Million dollar.” My job is only to make good art. Not speaking. My work is more serious than what I am speaking. In front of me, I have a futuristic compact machine. I do not have one of these…

RS Is –

EK Nobody can see their own face except in the mirror. And that is not correct. Left becomes right and right becomes left in the mirror. Nobody can see their real face. The other guy might laugh at you whoever you are. This is why I ask myself: who am I? Am I stupid or intelligent or a god? My art is always asking this question. Always, when I wake up, I start thinking about this – what do I do? What do I make? Finally, I eat. I go to the bathroom, always thinking constantly about what’s inside of me. What is the real thing? Nobody knows that infinity.

RK Rocky, do you want to answer one more question?

EK No.

Ross Simonini is a writer, artist, musician and dialogist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object, Verb