In this exchange, Gillick and Haacke discuss Documenta, the Bundestag and problems with institutions

Born in Cologne just before the Second World War, Hans Haacke has created works of unparalleled clarity that repeatedly remind us of the continual fight to preserve memory while exposing the social and political substructures of the cultural superstructure of the present. Making use of sculpture, photography and written documentation, his installations have long addressed issues of ecology and institutional frameworks. In 1959 Haacke worked as an installer and invigilator at II. documenta, the second edition of the documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany. In 2020 it was established that at least ten of the first documenta’s 21 organisers had been Nazis, and Werner Haftmann, who co-directed II. documenta, had been a member of the Nazi paramilitary Sturmabteilung group. The retrospective of Haacke’s work at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt-am-Main (that travels to the Belvedere in Vienna in 2025) includes the photographs that the then twenty-three-year-old Haacke took at documenta between July and October 1959 – capturing visitors encountering the new international art on display. By photographing the visitors Haacke unwittingly gives us insight into the context of the recent revelations. It’s a gesture of socio-political observation within the cultural field that can be traced through his work from those early years to the present.

Liam Gillick I went to see your 2019 exhibition, All Connected, at the New Museum in New York a number of times. I think it needed to be seen quite a few times: there were so many layers and so many shifts in the work. Do the new exhibitions take a starting point from that one?

Hans Haacke The new exhibitions are a retrospective too. But different to the New Museum. There will be many works that I have produced in Germany over the years [that were not on show in New York].

LG I first came across your work when I was living in England and still a teenager. Your project A Breed Apart (1978) referred to Leyland cars and trucks, and exposed the relationship between British vehicle production and the system of apartheid in South Africa. This had a very direct effect on me and was one of the reasons I joined the nightly vigil outside South Africa House. A little later in life I saw a small version of your Condensation Cube (1963–67) at [art collector] Jack Wendler’s house in London – and it has always fascinated me that the same person could make these two works.

HH I remember Jack; I visited him a few times in London. But I already knew him from before that time, when he was living in New York.

I filled some water into transparent plastic containers of simple stereometric shapes and sealed them … After a day, a dense blanket of clearly distinguishable drops has formed, all of which reflect light. As the condensation progresses, individual drops reach such a size that their weight overcomes the adhesive forces and they run down the wall, leaving a trace. This trace begins to grow over again. After weeks, a diverse juxtaposition of tracks has formed, each of which has a different droplet size according to its age. The condensation process never ends. The conditions are comparable to a living organism that reacts flexibly to its environment. The constellation of the drops cannot be predicted exactly. Within static limits, it changes freely. I love this freedom.

– Hans Haacke, speaking in 1965 on his Condensation Cube (1963–67). (All quotes drawn from Hans Haacke. Retrospektive, the publication accompanying the current exhibition.)

LG After spending more time in the USA creating works that presented systems that melded the scientific and the artistic, as a member of the Zero group, there is a distinct turn towards investigating the United States as a political-cultural machine in your work that takes place during the late 1960s. It seems to reflect something of philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse’s demands that artists turn towards new forms of critical practice. I only recently discovered that he gave a lecture at the Guggenheim Museum in 1969. In it he makes quite a distinct claim that art should refuse to be integrated with the institution. It seems like you were punished by institutions for exposing the machinations of the system of art rather than sticking to our relationship with natural forms and ecosystems. I remember reading you on this subject – that some important museum directors never worked again after defending your work.

HH I had a lot of problems with museums. I am still not welcome at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, but others are more open [to my work] now.

The Shapolsky real estate group, headed by Harry Shapolsky and comprising around 70 companies, bought, sold and mortgaged properties in 1971, often within the group … The 142 documented properties were located primarily on the Lower East Side and in Harlem, slum areas in New York in 1971, and formed the largest concentration of real estate under the control of a single group. The information for this work was taken from publicly available files of the New York Land Registry. Thomas Messer, then director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, rejected this work and two other works that had been produced for a solo exhibition at the museum. When the artist refused to withdraw the controversial works, Messer canceled the exhibition six weeks before it was due to open.

– Haacke, in 2006, on Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 (1971)

LG I always found your work useful – meaning literally useful. A toolbox for analysing systems. You wrote in the past about how you were trying to ‘do a job’. Looking back, you have done so much and addressed so many layers of society. It is such an extraordinary body of work. How do you feel about these big exhibitions? They are not easy to do.

HH In terms of the idea of a retrospective I am not able to do anything new with that any more. But I am in constant communication with the curators.

LG The work in the exhibition is not only about the compromised institutional framework. I think these new exhibitions will help people understand how many things you have dealt with. The work is not only about the relationship between the artist and the museum, but also about the artist’s relationship to the world and their political position – the degree to which we are all implicated. No one can operate outside of the system.

HH Yes. Yes.

LG The fact that there will be early work will help people understand that there is not so much of a contradiction between looking at an ecological system or a political system. They are an extension of the same thing.

HH Yes. You are right.

LG Could you talk about Vienna, to where this show will travel, a little bit? Your own relationship with Austria?

HH I made a remarkable exhibition in Graz in the 1980s. And also later on in Vienna at the Generali Foundation.

Since 1968, Graz has hosted the annual Steirischer Herbst, or ‘Styrian Autumn’, a publicly funded cultural festival. The festival’s 20th anniversary in 1988 coincided with the 50th anniversary of the annexation of Austria to the German Reich in 1938. For the 1988 edition, artists were invited to create temporary installations in public places that had played a significant role in the Nazi era. One of these places was the Marian Column in the city centre, a column crowned with a gilded statue of the Madonna that was erected towards the end of the seventeenth century to commemorate the Austrian victory over the Turks. When Hitler awarded the city the title of ‘City of the People’s Uprising’ on July 25, 1938, the celebration took place at the foot of the Marian Column. For the occasion, the column was hidden under a red obelisk decorated with the Nazi insignia and the inscription ‘And you have won after all.’ The claim referred to a failed Nazi putsch in Vienna on July 25, 1934. Graz was a Nazi stronghold in Austria from early on.

The obelisk was reconstructed for the Styrian Autumn in 1988 as a memorial to the victims of the Nazis with the addition of an inventory: ‘The defeated in Styria. 300 Gypsies killed, 2,500 Jews killed, 8,000 political prisoners killed or died in custody, 9,000 civilians killed in the war, 12,000 missing, 27,900 soldiers killed.’ One week before the end of the exhibition, the monument fell victim to a nighttime arson attack in which the bronze statue of the Virgin Mary was badly damaged. Within a week, the perpetrator and the instigator of the attack, a well-known 67-year-old Nazi, were arrested. In a trial, they were sentenced to two and a half years and one and a half years in prison respectively.

– Haacke, in 2006, on Und ihr habt doch gesiegt (And You have Won After All), (1988)

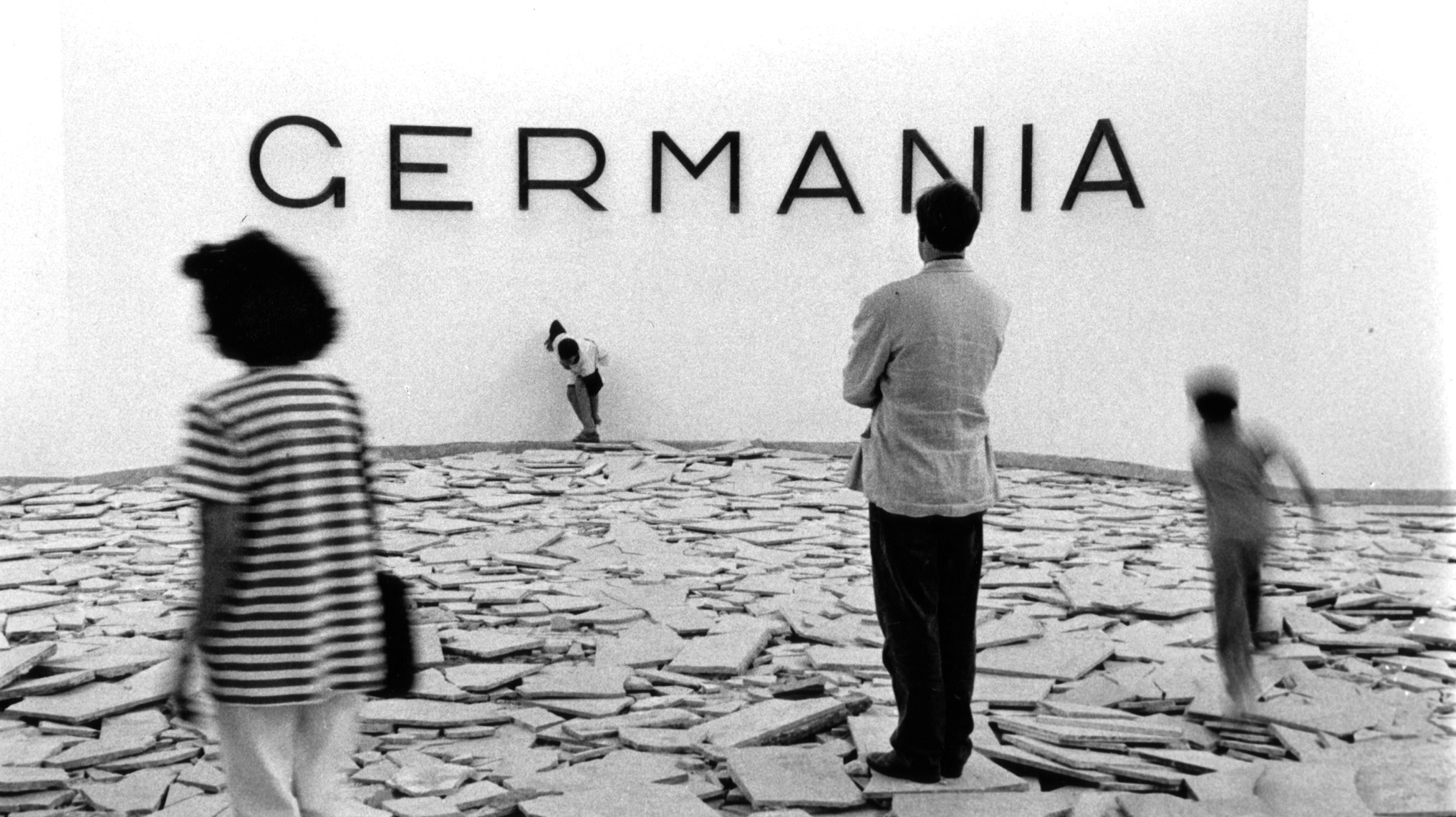

LG We both did the German Pavilion in the Venice Biennale. I was at your 1993 opening.

HH You were? Ha!

LG I did mine in 2009 right after the ‘financial crisis’ and we had a lot of problems with sponsorship as the big German corporations couldn’t be seen to be wasting money. So I asked if we could approach a supermarket or something more basic. I never got a good answer. They needed high-class sponsors. The processing of awareness never ends. I was rereading your book with the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu – Free Exchange (1995). It is such an interesting book. It addresses so many questions that many people think they have only just discovered, about identity and class in relation to culture. You wrote an appreciation of him in October when he died, where you ask, why would an institution like the Pompidou do a memorial for Pierre Bourdieu? How did you end up in this working friendship?

HH I remember that the first time we met was at a restaurant in Paris – the conversation started there and continued. I am also very fond of the cover of the book, it shows Calligraphie (1989). That was my proposal for the Palais Bourbon – which of course was not executed. But it was remarkable that Pontus Hulten, who was at the Pompidou way back then, and was a Swede and not French, invited me along with other people to make a proposal for the Palais Bourbon and I am still proud of what I proposed. It was the proclamation ‘We all are the people’, but in Arabic.

The members of the French Parliament are each to contribute a piece of stone from their constituency. The stones are assembled, worked and polished to form a perfect cone. A gilded, raised inscription on the surface proclaims the motto of the French Republic in Arabic calligraphy: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. A jet of water shoots up from the top of the cone. The water runs down its surface, then flows to the middle of a balustrade and falls through a breach it seems to have made in it into the main courtyard below, on which a large area in the shape of the map of France spreads out. In a four-year cycle, crops native to France are grown there: wheat, corn, rapeseed, cabbage, sunflowers, beans, peas and potatoes. In the fourth year, the field is left fallow. The water is channelled in a shallow channel with a slight gradient around the planted area towards the farm gate, where it disappears into an opening in the ground. All of the water is reused.

– Haacke, in 2004 on Calligraphie (1989)

LG This is still powerful and very necessary. I remember at the time thinking, ‘this is going to cause trouble’. Even if it was never realised – the work still lives, though, on the cover of the book.

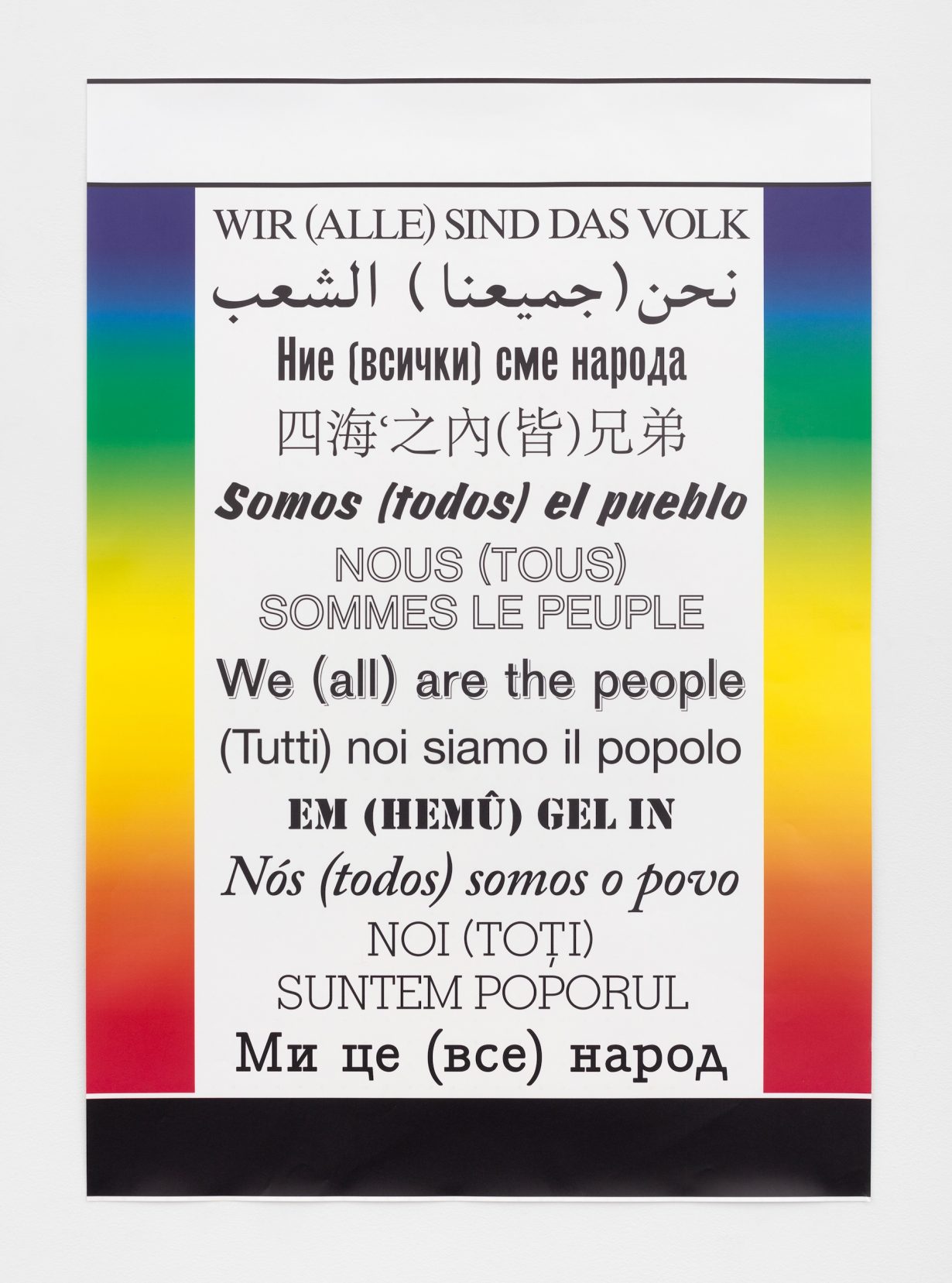

HH You know my proclamation ‘We (All) Are the People’ has been turned into a poster with the phrase in 12 languages and shown in many, many countries, including in the Middle East and the US. [In 1989, demonstrators chanted ‘We are the people’ at the People’s Police during protests in the former GDR. This contributed to the fall of the repressive regime and the reunification of East and West Germany.]

When I was invited to take part in a competition in 2003 to create a permanent installation in Leipzig to commemorate these events, the originally emancipatory slogan had been appropriated by xenophobic groups during demonstrations against new arrivals and refugees. I therefore proposed projecting an inclusive ‘We (all) are the people’ onto the walls of Leipzig’s St. Nicholas Church, where the demonstrators had gathered in 1989.

– Haacke, in 2017 on We (All) Are the People (2003–2017)

LG Your earlier works A Breed Apart (1978) and Der Pralinenmeister (1981) exposed the role of collector and chocolate manufacturer Peter Ludwig and his wife in their use of low-wage labour while garnering tax breaks for their collection – these works got into the nitty gritty of how cultural systems work to mask the operations of advanced capitalism. And now this has all finally led to the statement ‘We (All) Are The People’. I think that was always there in your exposure of the way art is controlled from behind a veneer. I think you asserting ‘We (All) Are the People’ via detailed work in the past has made it more difficult to hide in plain sight. More difficult for powerful people to escape the scrutiny of critical cultural practice.

HH I made a related work at the Bundestag, the German parliament. In 1997 there was a rededication of the phrase ‘Dem Deutschen Volke’ on the western facade of the building. That was originally a revolutionary gesture in relation to Kaiser Wilhelm. But by then the use of the word ‘Volk’ sounded somewhat nationalistic, and therefore I produced a dedication to the population instead, ‘Der Bevölkerung’ which opened in 2000.

The Bundestag had accepted a thematically related proposal of mine by a narrow majority. In reference to the dedication ‘TO THE GERMAN PEOPLE’ above the portal of the Reichstag building, my dedication ‘TO THE POPULATION’ was installed as a permanent installation in one of the two inner courtyards of the Reichstag building.

– Haacke, in 2017 on To the Population, 2000 (1999)

LG People were invited to fill the area around the large floor-based text installation with soil from their own communities. This eventually produced a melded ecosystem. It is a work that seems to bring together both central aspects of your work. The early interest in ecosystems that have their own logic, and what is now your universal reminder that we are all connected in ways we cannot control but we must restate and reaffirm. When you go back and read Jack Burnham’s writings on Systems Esthetics, and systems theory more generally, his ideas seem find resolution in this ‘To the Population’. More potently, in today’s Germany and beyond, the work carries a forceful assertion of acceptance.

Hans Haacke’s retrospective will be on view at SCHIRN Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, 8 November – 9 February