Twenty years after ‘the worst film of all time’, the aspirational auteur is back with Big Shark – and a new, accidental vision of America

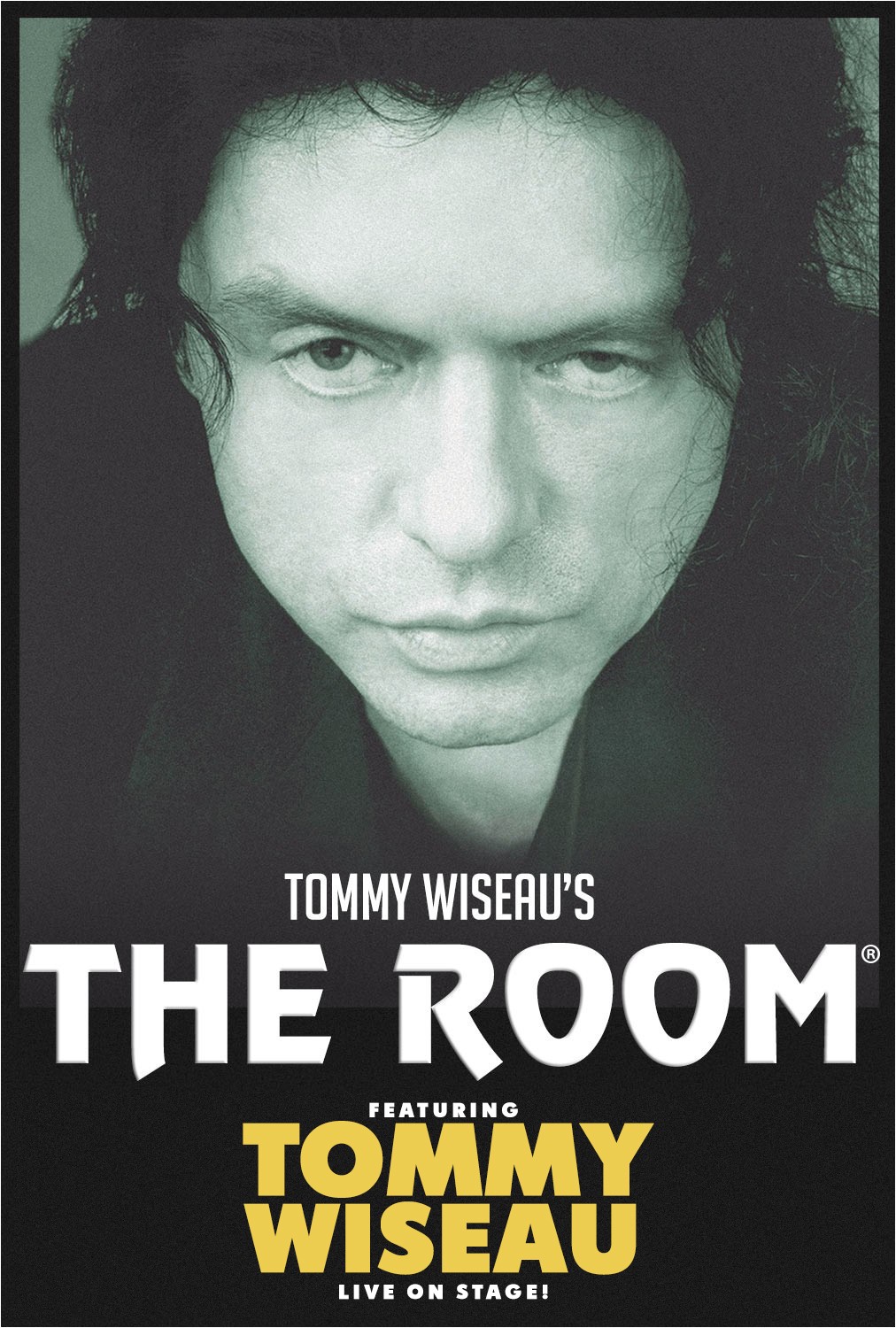

Tommy Wiseau is onstage, wearing an outfit as striking as it is made famous by the lore. There are the pitch-black wraparound sunglasses, which he never takes off (we are in the basement of a cinema) and thick leather gloves. During the event and in the new film we are here to see tonight, Big Shark, we will never see his bare hands. He wears a blue button-up shirt, a black vest and black trousers, and at least three chunky studded belts – “it keeps my ass up”, he has said. Audience members line up to the side of the stage, eager to ask questions. Wiseau breezes past queries he has nothing to say to – what he thinks about the Mission Impossible franchise, his knowledge of the history of sharks – and occasionally launches into tangents of his own choosing, often about the importance of following your dreams. The energy in the room is chaotic, raucous, warm, wild. Wiseau is particularly delighted by a question about his love of hats. When he introduces one of his lead actresses to the stage, he declares her the ‘decoration’ for the night. When that comment gets a stilted reception, he says that it is important to love women. As the Q&A draws to a close and the lights begin to dim for the screening, he declares triumphantly to the crowd: “Mr Spielberg, Tommy beat your ass!” – his shark is bigger.

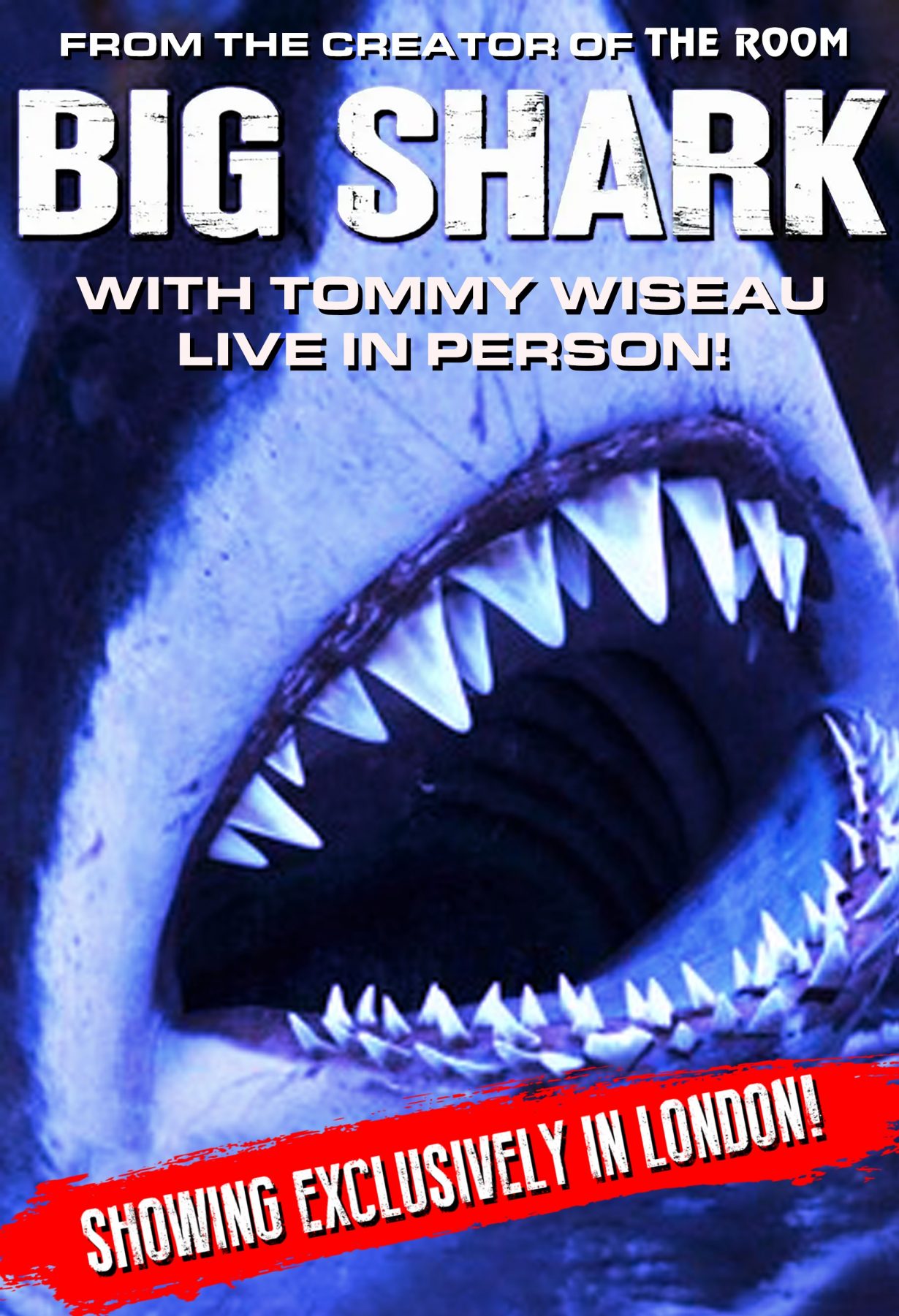

Ever since Wiseau’s first film, the 2003 drama-tragedy The Room – widely judged to be the ‘worst film of all time’ – confused, horrified and delighted viewers to become a global cult phenomenon, there have been rumours about his next feature. Those have been put to rest with Big Shark, released a long 20 years later. Shown in screenings in the US earlier this year, the film had its UK premiere at London’s Prince Charles Cinema this September. The trailer showed an enormous, cartoonish 35-foot shark terrorising modern-day New Orleans. Before the screening, I peeked at some audience reviews of the film. Many were ecstatic; ‘Makes Jaws looks like Troll 2’ one proclaimed (three years before the film’s public release). They read like irony-laden dispatches from The Room fans deeply familiar with the idiosyncrasies of Wiseau’s filmmaking, in which all considerations of plot, character development, pacing and basic sense are set aside, eclipsed by the overwhelming force of one man rendering himself a legend. Casting off the usual components that comprise a film, The Room is less a movie and more a fantasy-object in its purest form. Wiseau – who wrote, produced, directed and starred in it – plays the American everyman Johnny, who is betrayed by his femme fatale fiancée Lisa and his best friend Mark. The resultant narrative is pure myth, a dramatic and tragic ode both to the pure and good Johnny – perfect, beloved, cheated out of his promotion in the very competitive computer business and by his backstabbing friends – and to the real-life filmmaker-actor who brought him to life. No other character has a meaningful backstory; relationships do not make sense (‘I definitely have breast cancer’; ‘Look, don’t worry about it’). Everything else pales against the terrifying, awesome sincerity of one man making his bid for fame; the logic and coherence of the society surrounding him be damned. There is perhaps nothing more American.

In the Q&A before Big Shark, Wiseau announced that he wanted the new film to stand apart from The Room – expect no references or inside jokes. The opening scene of the new film quickly establishes that this is a different production from The Room. A suburban house is engulfed in orange and red flames, lit against a navy-blue night sky. It looks slick, if a little like a videogame; unlike The Room, some effort has been put into making the film look visually compelling. Wiseau plays the firefighter Patrick, who saves the day along with his firefighter buddies, Tim and Georgie. He spends his days fishing with his girlfriend Sophia and drinking beer with the boys. Shot on location in New Orleans, the film follows the friends strolling down the city streets, with lengthy scenes of them dancing to songs played by street musicians. I wondered whether this marked a conscious turn to naturalism after the high artifice of The Room’s constructed sets, glaringly obvious green screens and stationary cameras. And then, out of nowhere, shooting through the streets of New Orleans, arrives a gigantic and extremely animated shark.

I once read that cultural ethnographies can be far more revealing of the worldview of the examiner than the supposedly examined. Wiseau’s films confirm that: they are what you would get if you held up the American Dream in a distorting funhouse mirror and marvelled at the familiar but deeply weird result. (Exact details of Wiseau’s biography are still unclear, but in his memoir, The Disaster Artist, Wiseau’s friend and The Room co-star Greg Sestero hints that he grew up in a difficult family in a Communist eastern European country, and was drawn to the promise of America from a young age. Documentary filmmaker Rick Harper later discovered, after a lengthy investigation, that Wiseau grew up in Poznań, Poland.) The hallmarks are all there – boys and beer, women and shopping, extended montages of some sort of ball game – and yet everything just seems a little off. The scenes of male bonding are too long and over-earnest; the casual frat-boy misogyny a little too pronounced (Women! They are only ever after your houses!); the iconographic landscapes of America are, particularly by what seemed like the fiftieth shot of the Golden Gate Bridge in The Room, repeated to the point of hilarity. After all, The Room was the product of an aspiring serious-minded auteur drawing on old Hollywood tropes; it was an (accidental) pastiche of a Hitchcockian neo-noir, with a femme fatale in a red dress and a tragically doomed everyman modelled after Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). Big Shark, coming 20 years later, has forsaken the seriousness, but its commitment to an idea of America is no less fervent. The drama of Old Hollywood has been replaced by the action-man hero of the new. It makes sense that Wiseau plays a firefighter. When he discusses what to do about the shark with his friend, their conversation could almost be a parody of the American psyche. Do you trust the government to do anything? No! Screw the big state! Do you trust the military? Yes. We must respect the military. But for reasons somewhat unclear, they are held up at the moment, and so it is down to our boys to save the city.

Will Big Shark see the same success as its predecessor? The Prince Charles has planned some more screenings for the winter; the evening I was there, the audience – albeit a self-selecting group of fans – was raucous. Inside jokes have already bloomed, though unlike in The Room, many seem to have been deliberately planted for laughs, which makes it all less fun. The film swings between a sincere effort at an exciting action film and a self-consciously, frustratingly paced ‘bad movie’. It can be a riot when viewed among a crowd of true believers, but what made The Room so oddly compelling and cathartic to watch was its total unvarnished earnestness and desire to be great. The vast gap between the input effort and the unsuccessful result is not only hilarious, but deeply human (most of us know what it is to feel desperate, overwhelming longing, though strive to keep our failures private.) Big Shark loses that naivete, presenting itself up for laughs; perhaps there is an honesty in admitting that that initial magic cannot be captured. After people piled out of the screening – “that was fucking great!” – back out onto the street, some stayed for the follow-up. The line stretched impressively across Chinatown. After a chaotic wait downstairs – Wiseau stood at the bar, signing autographs behind a Perspex screen – we were seated. Then the familiar airy theme song; the first of many long shots of San Francisco. The Room was not the movie that premiered tonight, but this still felt, after all that, like the main event.

Rebecca Liu is a writer on arts and culture and a commissioning editor at the Guardian