From Ricky Swallow’s Borrowed Sculptures to Van Hanos’s Interiors, navigating LA galleries amid protests, lockdowns and curfews

A sensorial vertigo afflicts many East Coast transplants, enhanced by blinding sunlight and the ambient hum of air conditioners and helicopters. Early this spring, however, access to outside stimuli was cut. Meanwhile water was still scarce, and the air felt suddenly precious – newly coveted and feared.

In March, soon after quarantine, I began taking drives to the only acquaintances it was safe to visit in close range. I counted myself lucky to have a means of escape from my apartment that most of my New York-based friends, and the less fortunate citizens of this city, did not. I drove a rinky-dink 2007 Prius Hybrid with reasonable fuel efficiency and thus allowed myself this luxury. The inviolability one feels in a car has long been passed off as an excuse for selfish behaviour behind the wheel; it took on an additional false sense of hermetically sealed security, as from behind closed windows I spent mornings observing and photographing notable trees of Los Angeles’s East Side. With galleries, libraries and other nonessential businesses and centres closed, these trees provided a respite from the visual monotony of unmarked days, just as driving provided a bodily reprieve from the confines of my apartment.

I made regular pilgrimages to a Moreton Bay fig in Pasadena. Brought to California from Australia during the 1870s as specimen trees to beautify and enhance rapidly developing urban landscapes, Moreton Bay figs revealed over time their ability to grow to more than 60 metres in height, their exposed ‘buttressed’ roots now sprawling across sidewalks. Pasadena, with its palatial estates, is now one of the only residential neighbourhoods where this solemn, patiently elephantine tree is not in danger of being cut down. In the car I listened to Roberta Flack’s Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye (1969) on repeat. Many loved before us. I know we are not new. In city and in forest they loved like me and you.

In May, LA galleries began to cautiously reopen, adding appointment registries to their websites and implementing visitor caps and mandatory masks for entry. Then one more Black citizen was brutally murdered by a white law officer, and the scales tipped. I am not the right person to speak to this, and the piece I set out to write is about galleries and trees. I am trying instead to listen to others, better versed and equipped.

The next month, amid protests, lockdowns and curfews, I registered to see Ricky Swallow’s Borrowed Sculptures at David Kordansky Gallery in Mid-City. The Australian-born Angeleno’s latest sculptures continue his work recreating domestic materials in cast and painted bronze, their impressive trompe l’oeil effect overshadowed by the delicacy of their readymade referents. One lone form, Stringer (2020), whose motif suggested a stair rendered from coils of rope, graced the gallery’s southern wall like a Celtic knot. A bronze rocking chair, Rocking Chair with Rope (meditation chair # I) (2020), cast from a model in the artist’s studio, appeared to hang, as though suspended from bronze ropes strung to a nonexistent ceiling-mounted hook, with the tensile restraint of a Fred Sandback installation. I shared the gallery with only one other visitor. Another stood patiently at the door, waiting for one of us leave.

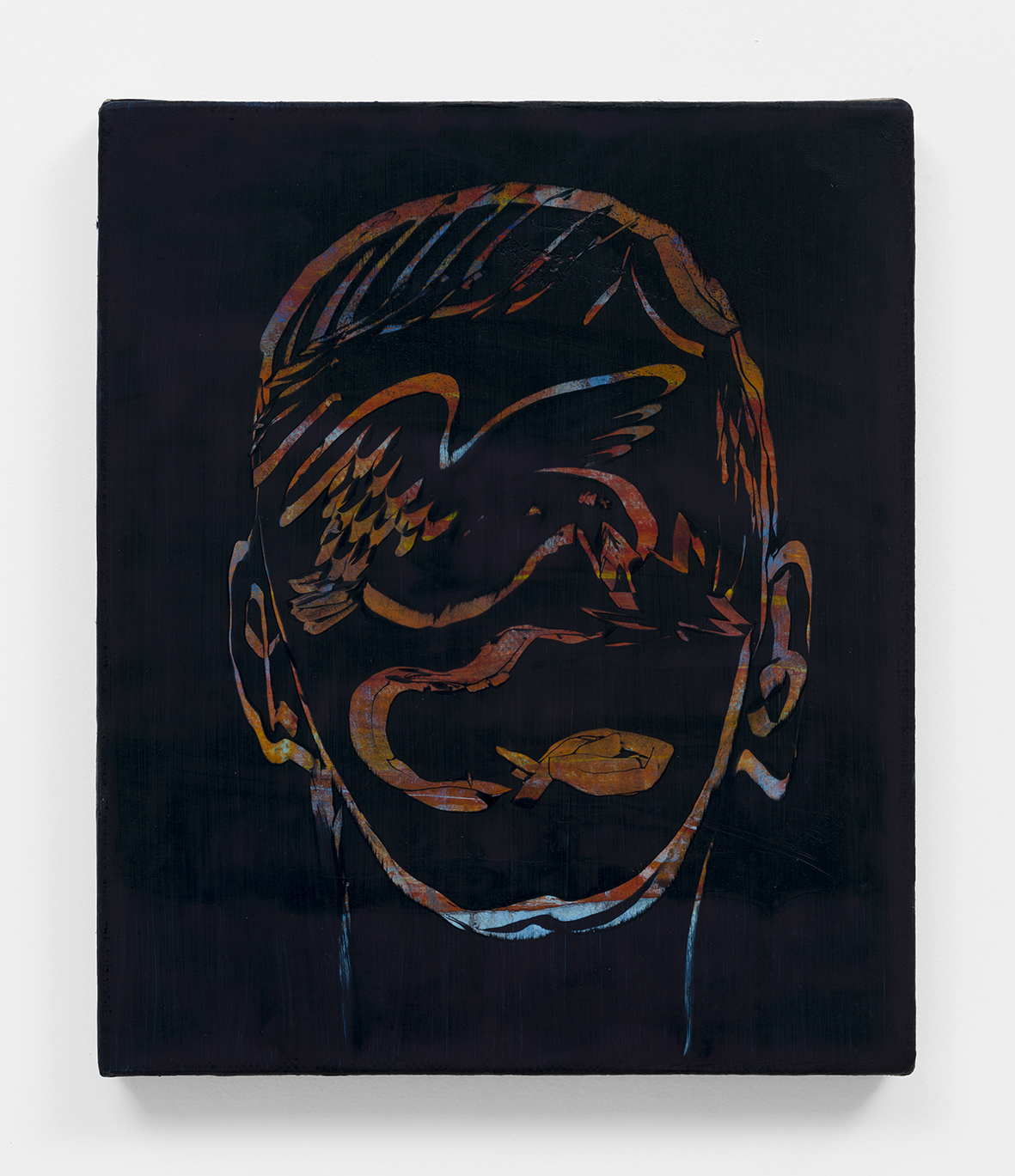

I made an appointment at Château Shatto downtown to see Van Hanos’s Interiors. Characteristically virtuosic (the New York-based artist, who recently relocated to Marfa, is among the most facile painters currently working) and teasingly referential, this new set of works demonstrated stirrings in the evolution of Hanos’s conflicted attitude towards the heroic oil painting. Among the exhibition’s largest canvases, Interior (2020) ensconced a deadpan ‘pictorial’ painterly view out from a paned window within a palette-knife-scraped frame that made explicit allusions to Gerhard Richter. The adjacent, modestly scaled Eagle, Crow, Snake, Fish Face (2020) took this reference to its art-historical endpoint: here the artist had used this chromatically striated scraped canvas as an underpainting, burying it beneath a coat of Ad Reinhardt-esque black before scraping a portrait onto its surface to reveal its base as if it were a Rainbow Scratch craft paper.

The appointment system was itself new and strange. I’d previously tried to see shows with as few preconceptions as possible. (Although with galleries strewn across miles and potentially hours of traffic, this had already proved somewhat impractical.) On the other hand, these restrictions were conversely appealing when you remembered summer openings of prior years – edging past clots of sweaty revellers to see the work they were standing in front of. An appointment made a visit intentional; the visitor cap created a dual sense of intimacy and urgency. Masks, on the other hand, are simply a present necessity as well as a gesture of respect and appreciation for the many people who make these visits possible.

I discovered a trio of shrubs pruned in the shape of giraffes in a garden I can only appreciatively describe as extremely whimsical, and was tipped off to the location of a yucca whose trunk resembled musculature riddled with bulging cysts. The days grew hotter earlier. On cool mornings, however, it finally seemed safe again to climb the 383 stairs off La Loma – huffing through a mask, passing a young oak whose bow had extended into the pathway and been tagged with a red ribbon so that walkers wouldn’t hit their heads. Like the Moreton Bay fig, the oak can grow to massive proportions. Unlike the imported tree, it is native to California, and its nutritionally dense acorns historically provided sustenance for indigenous peoples.

Among the venues that most nimbly adapted to the city- and state-wide ordinances was Parker Gallery, in Los Feliz. The residence-based gallery hosted a series of two-week-long outdoor exhibitions entitled Sculpture from a Distance (parts I, II and II), featuring celebrated LA artists Melvino Garretti and Peter Shire and emerging artists including Alake Shilling and Anne Libby. Circumventing the need for reservations (although not masks), the shows were designed with comfort and safety in mind; one could wander freely through works installed on the grass and mounted to the sides of the building. As of August, the trees continue their efforts to purify our air while cars (mine included) poison it. Leonard Cohen’s original lyrics to Flack’s cover were, “Many loved before us. I know that we are not new. In city and in forest they smiled like me and you.” Flack’s rendition is better, but the poet knew what he was doing. ‘Smiled’ is both less expected and infinitely sadder than ‘loved’ while signalling essentially the same thing – even from behind a mask.