‘Archipelagic Void’ by Minsuk Cho’s Mass Studies can’t shake off the jaded air of having a Kensington budget without the imagination to do much with it

Archipelagic Void – the title of the latest Serpentine Pavilion – is, perhaps unintentionally, a perfect metaphor for the state of contemporary Britain. Beneath the restless quest for novelty, there’s a weary sense of something yawning and empty. No Blair-era triumphalism here (all dazzling grins and ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ ad nauseam). Instead, there’s a palpable malaise running deep in Albion’s soil after fourteen years of Tory rule. Korean architect Minsuk Cho’s Mass Studies was in the invidious position of being awarded this year’s big-budget architectural commission, at a time when the social and political landscape feels so depleted against a backdrop of Brexit, cuts to art funding and a sense of reheated nostalgia currently permeating the culture industry. Though Cho has attempted to wrest something from 2024’s horror vacui, he has instead created a monument to the status quo.

Archipelagic Void constitutes a series of five ‘island’ buildings’ connected by a central, circular courtyard, in reference to the design of traditional Korean houses with a ‘madang’: an open space which serves to connect various quarters. Indeed, notions of ‘fluidity’, communality and the spatially free-form have become ubiquitous architectural principles in recent decades – from Apple’s ring-like Californian headquarters to Zaha Hadid’s anti-vertical flow. Cho’s structure, with its lack of adjoining walls or sense of enclosure, also allows for a kind of curious drift: people move seamlessly between the park’s pathways and the wider landscape of the Serpentine’s South lawn.

Made largely from timber, the roofs of each connecting structure radiate from a central steel ring in a starlike arrangement, all angles and strange, sloping perspectives. In painfully modish terms, Cho has created each of the Pavilion’s five different spokes as what the press release calls a ‘content machine’. The largest of these, ‘The Auditorium’, is a long corridor in black-stained timber with a steepled roof running down to the Serpentie’s South Gallery and outfitted with windows in kitschy hot-pink perspex. Diagonally across the way, a bright orange pyramid points skywards. ‘The Play Tower’ comprises two levels of orange nets, in which visitors are ‘invited to climb and interact and experience the space in a tactile way’. That is, so long as you adhere to its forbidding list of rules (‘Please only stand on the rope’) and cramped, claustrophobic dimensions (which can hold ‘a capacity of 6 children, aged 5-16, permitted at any time’). Your kids would likely have more fun in a suburban shopping centre’s play area.

‘The Gallery’ hosts a sound installation created by musician and composer Jang Young-Gyu, whose The Willow features traditional Korean music alongside sounds recorded from the surrounding Kensington Gardens. All twittering birds and meditative ambient noise, its offering of repose is somewhat redundant in one of London’s most manicured parks, as if being stuck in a feedback loop of tasteful privilege. Nothing arrests the eye: only grey matte panels and a drably matching tiled floor. Another structure, ‘The Library of Unread Books’, an installation by Heman Chong and Renée Staal, is conceived as a ‘living’ reference library. The stacks of books – including from the Serpentine’s own collection – are presented, according to the press release, as a ‘collective gesture, addressing notions of access, excess and the politics of distribution’. Which is all well and good if the library weren’t so oddly unwelcoming, with its austere look and lack of seating. (I wasn’t allowed to take a copy of Elias Canetti’s 1960 Crowds and Power far from the sight of one of the staff, turning the ‘unread’ into a prohibition rather than a trenchant concept.) The Pavilion’s final section, ‘The Tea House’, has been conceived as a ‘nod to the history of the Serpentine’ before its relaunch as an art gallery in 1970. Yet this invocation of the past merely highlights a culturally impoverished present: the ‘Tea House’ in question is an outpost of the bougie coffee chain Colicci, selling tuna sandwiches for £5.95 or scoops of ice cream for £4. More bland, cookie-cutter capitalism, then. If this is the Serpentine’s history, it’s not so much been forgotten as turned into anodyne parody. In over-reaching for cultural reference points, Cho ends up producing a flattening mishmash, rather than the nuance he seems to be striving for.

Much like modern Britain, the 2024 Pavilion finds itself desperately struggling for meaning and a coherent sense of itself. As such, it feels like a continuation of London’s intractable modern march towards ‘redevelopment’: the Thomas Heatherwick-designed Coal Drops Yard model of recycled brand names and grayscale conformity, its user-friendliness functioning like an upscale mall and based on a simple metric of consumerism (look! A bench to eat your overpriced sandwiches!) rather than any kind of flair or originality. This latest iteration can’t shake off the jaded air of having a Kensington budget without the imagination to do much with it.

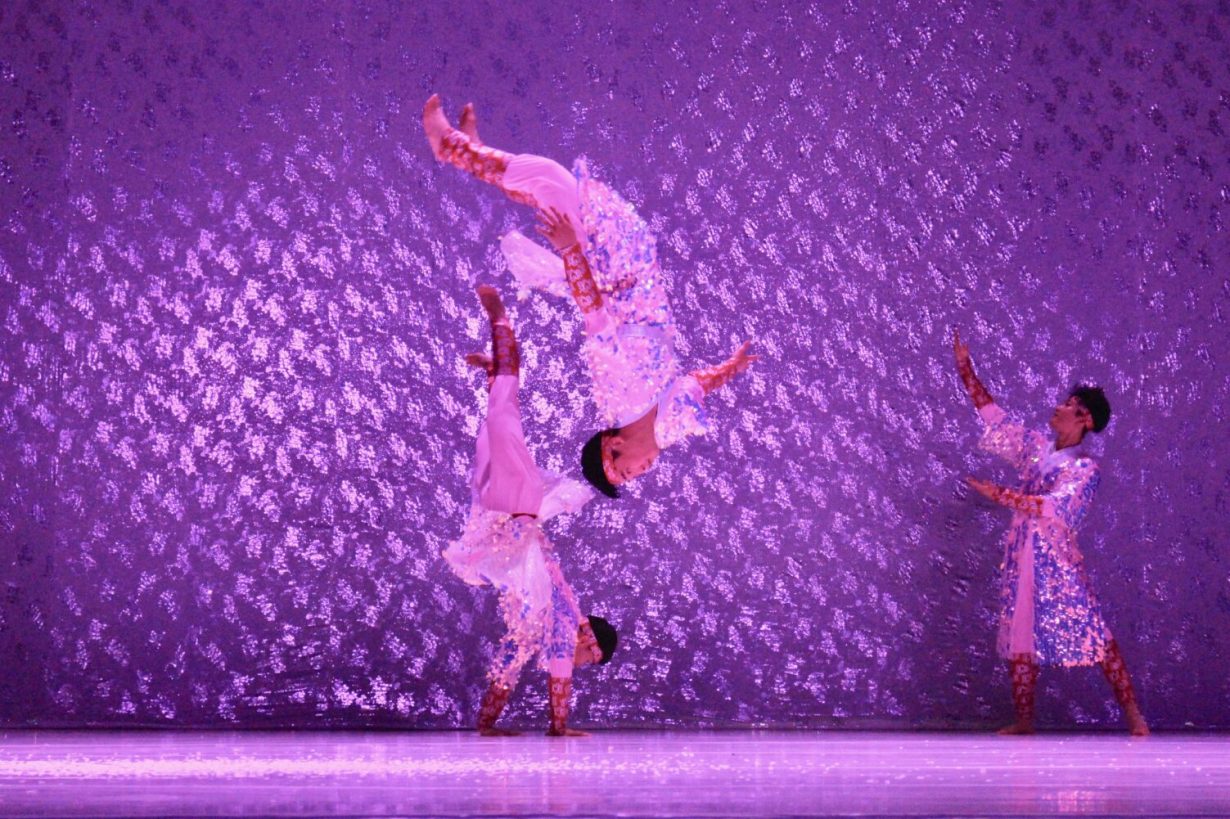

South Korean choreographer Eun-Me Ahn’s North Korea Dance, performed over two evenings in June, lent the Pavilion a kind of cohesion and vitality that isn’t otherwise extant. Switching registers with ease, from the discipline of traditional ballet to a hyper-speed K-pop club night, Ahn’s piece makes reference to the seventy years of division between North and South Korea and its fracturing effect on Korean culture. After opening in The Auditorium with a musician, plaintive and bathed in blue spotlights, plucking a Korean gayageum instrument (stringed and played on the floor), a white spotlight then switched onto the rear doors of the Serpentine South gallery. There was Ahn, dressed in a bejewelled white dress, her movement languid but precise. The music shifted to pulsing bass and skittering trap beats as a dancer dressed in Korean military uniform held up an iPad that counted the year from the early twentieth-century up to the present. Performers in golden uniforms, holding multicoloured pom-poms, sang a song called ‘Glad to Meet You’ (Lee Jong-oh, 1991) while waving ecstatically. The performance then segued into an extended section, silent and solemn, as dancers wearing red ribbons and cloth boots made nimble and intricate steps. A following group turned to acrobatics, leaping into flips and forward rolls while wearing eye-popping costumes of red bubbled plastic. Ahn appeared again, lip-syncing to ‘Whistle’ – a 1991 pop song by North Korea’s Pochonbo Electronic Ensemble adapted from a 1949 poem of romantic obsession by Cho Ki-chon – while wearing a crown and teetering on improbably high plastic heels, before the music turned into throbbing, nightclub euphoria.

This was an enthralling spectacle, even if its theme of synthesis and communication between different (and even opposing) nations often felt glossed amid the visual rush. As the audience filed out into the late summer evening, I couldn’t help but feel the Pavilion was once again being returned to its heretofore state: an hollow vessel filled only by its ambition. In the same way that much of central London feels increasingly like a homogenous redevelopment opportunity for offshore investors, the Serpentine Pavilion fits too neatly into its surrounding. It’s yet another advertising billboard flogging an uninspired product: a flashy commercial franchise full of lofty rhetoric, but more intent to serve overpriced coffee and undercooked ‘content’ than rise to the height of its ideas.

Daniel Culpan is a writer based in London