The designer, known for his signature heat-pressed pleating technique, saw fashion as inherently optimistic and clothing as ‘like beautiful architecture for the body’

‘Make me a fabric that looks like poison.’ This is what Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake apparently once instructed his textile engineer, Makiko Minagawa. Miyake’s idea of fashion was often beautiful and always technically challenging. Over a career spanning four decades, his work would demonstrate an extraordinarily virtuosic range, from red plastic moulded bustiers with flirtatiously flared peplums to colour faded menswear drawing on shibori, a traditional Japanese tie-dye technique. He designed multicoloured flying saucer dresses that could be compressed like paper lanterns to fit into a suitcase and tubular industrial knits that the wearer could cut to size along a dotted line. Most importantly, perhaps, Miyake pioneered an innovative method of heat-pressed pleating that would become his distinctive fashion signature. His clothes were joyful and the news of his death, aged 84, marks the loss of a great twentieth-century fashion visionary.

Unsurprisingly, Miyake’s unique style attracted some notable devotees, including Grace Jones, whose own strikingly sculptural form especially suited Miyake’s designs. Steve Jobs discovered Miyake’s black polo-necks on a trip to the Sony factory in Japan in the 1980s, observing the elegant Miyake-designed grey uniforms. He commissioned 100 black turtlenecks for himself, reputedly at a cost of $175 apiece. Zaha Hadid, when pictured, was often swathed in black Miyake micro-pleats. It’s clear to see how the fashion designer and the architect might share an interest in shape, form and the dynamic intersection of planes. For Miyake, the connection between art, architecture and fashion was real. Fashion, he observed ‘could be like beautiful architecture for the body’. At the simplest level, designing was an act of construction and Miyake determinedly committed his life to creating.

Born Kazunaru Miyake in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1938, he was seven-years old when, while cycling to school on 6 August 1945, US forces detonated an atomic bomb, devastating the city. Over 60 years later, writing in an op-ed for The New York Times in 2009, Miyake described how his mother, who had suffered serious burns, continued to work as a teacher despite her injuries. She died of radiation exposure within three years of the bombing. ‘When I close my eyes,’ he wrote, ‘I still see things no one should ever experience: a bright red light, the black cloud soon after, people running in every direction trying desperately to escape – I remember it all.’

As a child, he leafed through his sister’s fashion magazines and turned to drawing. This led him to a graphic design degree at Tama University in Tokyo, where he graduated in 1965. Soon after, he headed to Paris, following in the footsteps of fellow Japanese designer Kenzo Takada (later, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo would follow too) where they studied together at the storied Chambre Syndicale de la Couture. In the following years, Miyake was apprenticed to French couturier Guy Laroche, and then to Hubert Givenchy. But haute couture rang hollow in a tumultuous Paris whose streets teemed with student protests. Visiting New York in 1969, he discovered a different cultural scene, meeting Christo and Robert Rauschenberg – the beginning of a lifelong affinity with visual artists. Meanwhile in Tokyo, the 1970 World Expo was showcasing the modernity of Japanese arts. Miyake’s work would become a cultural bridge between New York, Paris and Japan, bringing together the heritage of traditional Asian crafts with a radically innovative imagination.

In New York, he founded the Miyake Design Studio and launched his first collection in 1971. It featured jersey dresses with tattoo-style prints of Jimi Hendrix and coats in sashiko embroidery–a quilting technique associated with Japanese peasants – and was enthusiastically received by US Vogue and Bloomingdale’s. His landmark collection, though, would come in 1993 with ‘Pleats Please’. There you can see his unique sensibility: the expert drapery of European couturiers Madeleine Vionnet and Mariano Fortuny meeting the Japanese art of origami. Miyake’s innovation was to use synthetic materials, cutting patterns to three times their intended size and heat pressing pleats. Later collections would experiment with high-tech thermoplastic fabrics, crushed, creased and heat sealed into shape. But Miyake could champion Asian ikats and paper clothing inspired by Japanese farmers as easily as he could fabricate jackets from monofilament polyamide and a shimmering holographic sheen. ‘There are no boundaries for what clothes can be made from’, he observed. ‘Anything can be clothing.’

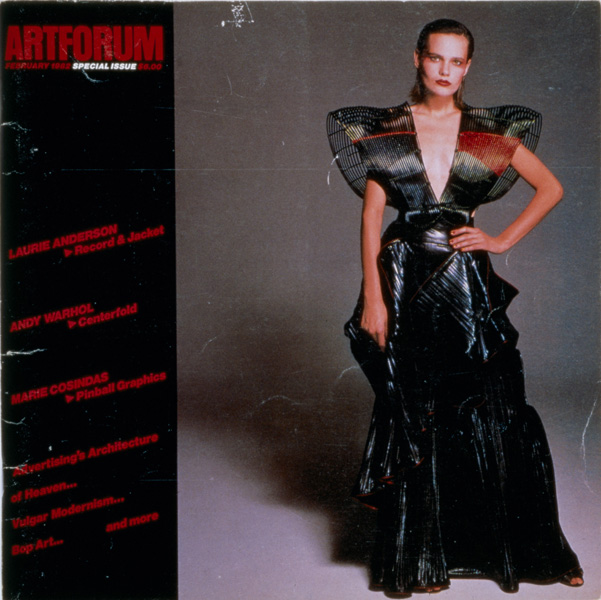

Although he never regarded himself as an artist, Miyake will almost certainly be remembered as one the great twentieth-century designers who made the distinction between art and fashion harder to discern. The photographer Irving Penn was mesmerised by his work and Miyake would send him trunks of clothes to be photographed, season after season, for over a decade. In turn, Miyake acknowledged that ‘Penn’s photographs allow me to see my own designs’. His ‘Guest Artist’ series, running from 1996-98, featured images from artists Cai Guo-Qiang, Yasumasa Morimura and Tim Hawkinson, screen-printed onto heat-pleated Miyake dresses and overalls. As early as February 1982, Artforum put a voluminous, structured black Miyake dress on their cover, a nod to fashion’s place at the vanguard of art. His show, ‘Bodyworks’, which began in Tokyo in 1983 and travelled to major museums in San Francisco, Los Angeles and London, might well be regarded as one of the first major solo fashion exhibitions. Suspended over pools of black dye, the garments were displayed in conceptual rather than chronological order. At the 1996 Venice Biennale, Miyake’s clothes were exhibited across the city. Since then, his work has been displayed at MoMA, the Met and the V&A, as well as The National Art Centre in Tokyo.

In the late 90s, Miyake retired to devote himself to research. His influence, though, would remain visible, both in the generations of Japanese designers that followed him and in his broader understanding of fashion as a space for limitless experimentation and imagination. Although many in the fashion world will be saddened at the news of his death, his clothes will be remembered as he wished, as ‘things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy’.