Qaumajuq museum in Winnipeg, Canada, is a groundbreaking step in the decolonisation of our arts institutions

Hosting the largest public collection of contemporary Inuit art in the world, the recently opened Qaumajuq – a museum connected to the Winnipeg Art Gallery – is a groundbreaking step in the indigenisation and decolonisation process of cultural institutions in Canada and beyond. Pronounced ‘kow-ma-yourk’, Qaumajuq means ‘it is bright, it is lit’ in the Inuktitut language, and the reference to light is apt for the 3,700sqm building, designed with wide expanses of glass to illuminate a three-storey ‘visible vault’ that presents approximately 5,000 Inuit carvings, best seen in natural light. The vault display is organised by community of origin, with up to three generations of related artists shown together, emphasising regional differences between local materials. By night, the glass vault lights up Qaumajuq like a lantern.

Above it, the scalloped white limestone facade of the building’s exterior undulates like a calved iceberg, giving the white-walled main gallery inside an organic sensibility. Circular skylights bring daylight into this expansive space, recalling perhaps seal holes cut in the ice or the ceiling of an igloo. While Michael Maltzan’s architecture pays tribute to the epic qualities of Arctic light, where some communities experience extended periods of sunlight and darkness, the museum was developed in a reconciliatory and hopeful spirit to publicly shine a light of acknowledgement and education on Inuit and Indigenous life in the context of the devastating legacy of colonial contact.

In recent times and especially over the past year, during which ‘normal’ practices have been radically disrupted worldwide, questions of justice and decolonisation have come to the forefront of the cultural conversation with a call not to return to normal. If museums have only recently been more widely considered as primary locations for the maintenance of colonial ideology, and thus sites for activism towards transforming the hegemonic sociopolitical values they embody, the colonial structure of the museum as an ‘othering-machine’ demands systemic rethinking. Its fundamental pretence as a democratic, neutral space can no longer be upheld; the museum must always be considered as a partisan extension of power relations.Yet while it is well known how artworks and artefacts function to articulate dominant historical narratives (usually white and patriarchal) and dismiss, obscure or rewrite others (usually BIPOC), the strategies for museological revision have for the most part been limited in scope. In contrast, the development of Qaumajuq by the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), has addressed these structural challenges explicitly.

Some history: when WAG Director Stephen Borys arrived in 2008, he recognised that the WAG’s Inuit art collection, which had grown steadily since the 1950s, was the world’s largest. Four years later, he initiated an Inuit taskforce to guide the development of an Inuit Art and Learning Centre. This taskforce evolved into the Indigenous Advisory Circle, which has led the decision-making process to ensure that the then provisionally named Centre for Inuit Art truly empowered the Indigenous communities involved. The project took on new urgency when the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission published a list of calls to action in 2015, aimed at reconciling Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples and supporting Indigenous cultural practice and languages, many of them on the verge of extinction.

At this time, Winnipeg-based Anishinaabe artist and curator Jaimie Isaac joined the WAG, creating exhibitions that examined Indigenous questions from a contemporary perspective. Her 2015 show, We Are On Treaty Land, addressed the fundamental but often overlooked fact that Winnipeg is on Treaty 1 territory, presenting artists from this region and, significantly, following Indigenous protocol for Treaty land acknowledgement. Boarder X (2016) featured a functioning skateboard ramp built in the WAG’s expansive ground-level hall, attracting Indigenous youth who would likely never have visited the WAG otherwise. Such work built trust and partnerships with local Indigenous communities and organisations, raising issues heard nationally and internationally, and led to INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE (2017), the largest Indigenous-led exhibition the WAG has ever produced. The following year, construction began on the new building, and in 2020, after virtual consultations between Indigenous language-keepers and elders from both the Inuit and the First Nations and Métis from the Winnipeg area, the group decided on Qaumajuq for the centre’s name. It took the further step of naming all the centre’s public spaces, often relating them to social and natural features, which simultaneously shut out corporate sponsors. The names were given in the following languages: Inuktitut (Inuit), Inuvialuktun (Inuit), Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe/Ojibway), Nêhiyawêwin (Ininiwak/Cree), Dakota (Dakota) and Michif (Métis). This sacred act of identity formation was empowering in performative ways and is critical to institutional trust.

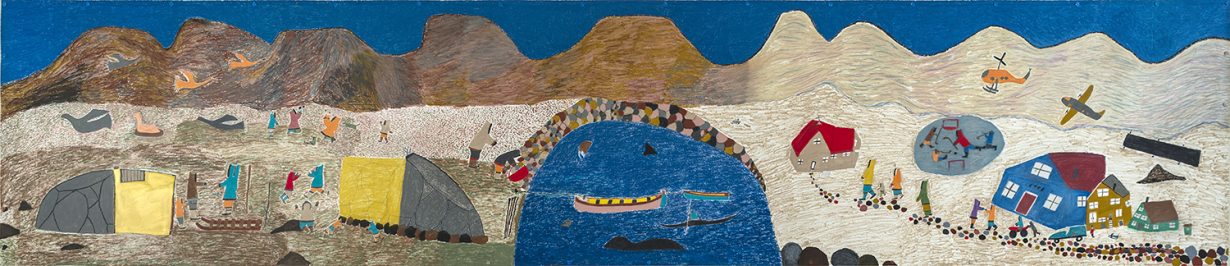

Qaumajuq opened in March with INUA (‘life force’ or ‘spirit’ in numerous Arctic dialects), which features an intergenerational and intersectional (with 2SLGBTQ+ artists represented) diversity of artists and over 100 artworks across a range of media, communities and scales. The importance of Inuit lineage and continuity is made powerfully clear by the introduction to the exhibition via four artworks, one each from the curators – Heather Igloliorte, Kablusiak, Asinnajaq and Krista Ulujuk Zawadski – who come from the four Inuit regions of the Arctic. Innovatively, the exhibition steers away from received notions of Inuit art and display formats. It is without walls, but structured by the informal architectures of the Arctic, including a shipping container (or ‘sea can’), a grandmother’s kitchen and a hunting shack, and presents an image of the north from the Inuit perspective. While respectful of historical work, with displays of prints and carvings up to 80 years old, the exhibition’s focus is on future-forward visions: such as Glenn Gear’s immersive video installation Iluani/Silami (It’s Full of Stars) (2021) and Jesse Tungilik’s Seal Skin Spacesuit (2019). The future is in fact a perennial theme in Inuit art and INUA is also an acronym for ‘Inuit Moving Forward Together’, yet the visionary impulse always remains intimately interconnected across time, land and community.

Qaumajuq reflects this hopeful, grounding force amidst the legacy of colonial brutality, suppression and violence. As Omaskêko Cree artist Duane Linklater asked during a discussion titled ‘Decolonizing the Collection’ at The Graduate Center, CUNY: what does decolonisation actually mean? Words such as decolonisation and justice are often instrumentalised by conservative structures seeking a progressive image. Isn’t the ideal, conversely, a return of lands and territory to ancestral peoples? If this sounds radical, it nonetheless reflects the urgency above and beyond incremental reforms to fundamentally transform or replace old institutional frameworks (of representation) that were established when colonial forces were at their peak. In this context, Qaumajuq is a unique and encouraging approach, in which Indigenous voices are not only responding to but leading the conversation. As curator Jaimie Isaac noted in the opening ceremony, what is critical is ‘making space’: safe space, for the inclusion of more voices. The spaces of Qaumajuq were built for this reconciliation, not just as an archive and display but as a ‘working’ structure, facilitating research, production, education, exhibitions and, importantly, ceremony. In fact, Qaumajuq opened in March with a ceremony by the Seven Nations of Manitoba involving spirit purification and protection rituals, an unprecedented acknowledgement and blessing from Indigenous elders for this institution, which might be called revolutionary in many ways.

INUA is on show at Qaumajuq, the Inuit Art Centre at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, until December