The resurgence of folk horror films explores buried anxieties – personal, social, spiritual – but whose anxieties, exactly?

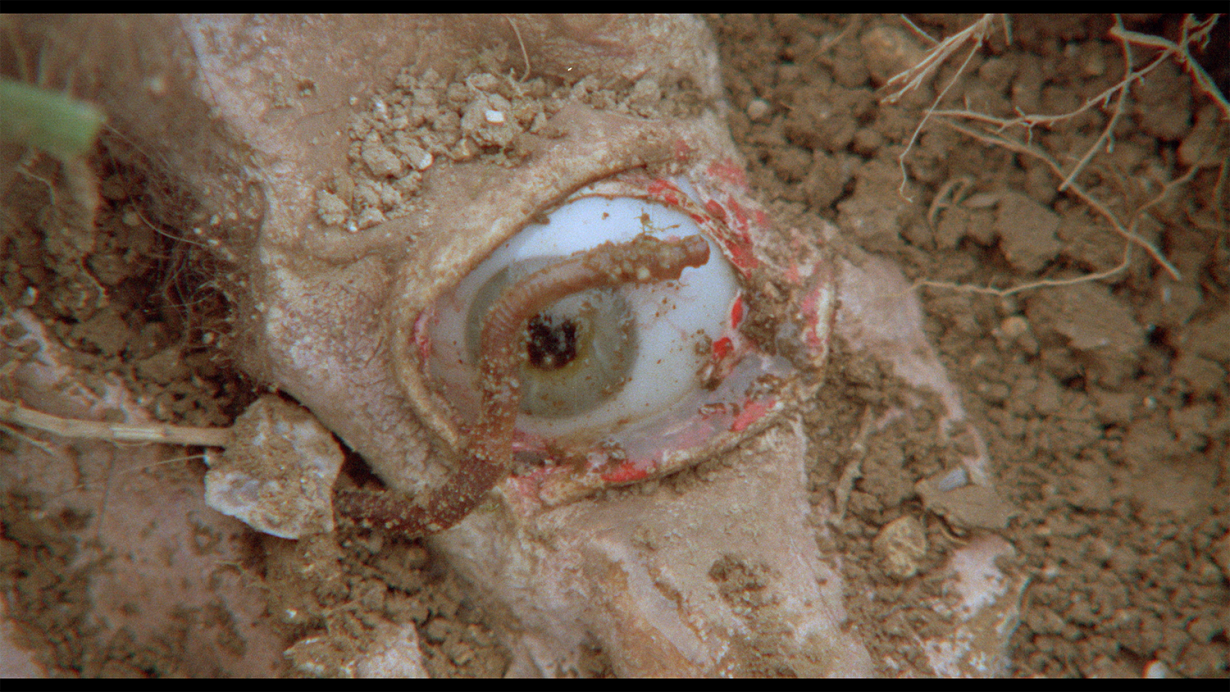

The remote community you just moved to has some eccentric, decidedly pre-Christian rituals. There’s something strange about the games the local children play. A cursed, ancient artefact is unearthed, unleashing malevolent desires in the villagers. You should leave, but somehow you can’t escape this place.

Folk horror – horror that taps into folkloric rituals and remembrance of suppressed traditions, the strange energies of landscapes, distant echoes of paganism, and everything else that modernity tried to leave behind – has been having a resurgence lately. The idea’s been floating around for a long while of course, getting retrospectively applied (if in a bit of a scattershot way) to various artists and media: from the ghost stories of M.R. James and Arthur Machen to the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft and blockbuster satanic-panic tales of Stephen King. The sound of folk horror can be heard in the 1970s psych-folk music of Comus, the hauntological soundscapes of the Ghost Box label, the occult emanations of Broadcast, and so many others.

But it’s on screen that folk horror fully comes to life. Recent years have produced a slew of screamers: Ben Wheatley’s 2021 film In The Earth is a toe-turning immersion into the strange and violent energies of the English countryside, and continues that director’s fascination with British horror, from Kill List (2011) and A Field In England (2013). Felix Barrett and Dennis Kelly tapped into the painfully specific creepy-British-island-community-you-cannot-escape story with their TV miniseries The Third Day (2020), while Chris Baugh’s comedy-horror film Boys From County Hell (2020) unearthed the slumbering vampires in Irish hills. And Charlotte Colbert’s She Will (2021) injects #MeToo with the supernatural power of witch hunts and burnings. The US has its own buried malignancy to deal with (and profit from) as well. From Robert Eggers’s cursed-coming-of-age flick, The Witch (2015), to Ari Aster’s head-wrenching Hereditary (2018) and gut-splaying Midsommar (2019), to Scott Cooper’s Antlers (2021) that revisits the Native North American legend of the cannibalistic Wendigo spirit.

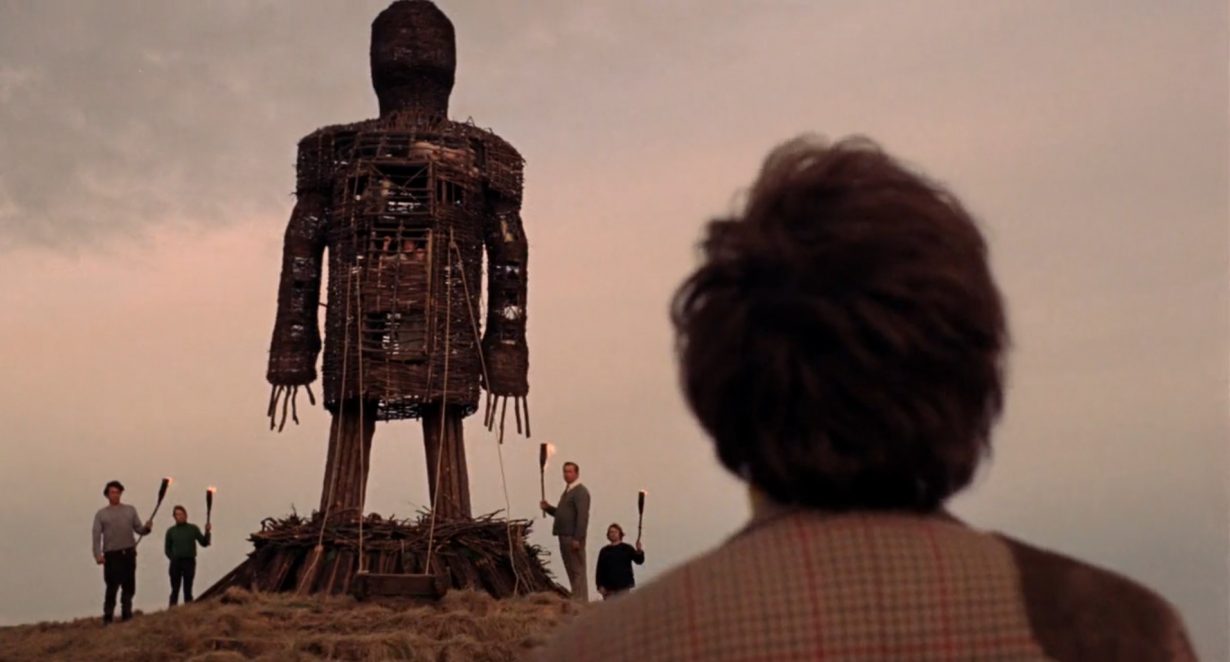

Whether ghostly or visionary, haunted or enchanted, the legacy of late-twentieth-century British cinematic experience runs deep in folk horror – especially in the so-called unholy trinity of Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder General (1968), Piers Haggard’s The Blood On Satan’s Claw (1971), and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). Though each quite different from the other in style, theme and intent, they are considered foundational in the folk horror canon. All British-made, all from the heady 1960s and 70s and, to varying degrees, all infused with the back-to-nature, explorative spiritual revivalism, and political upheaval of their times.

And so it’s natural that most writing about folk horror is British. Initiatives like the ongoing Folk Horror Revival & Urban Wyrd Project have worked towards trying to grasp the fleeting wisps of the folk horror spirit. Through publications, playlists, an online community and other activities, they work to reinterpret what folklore and folk horror might mean for contemporary British identity in a globalised culture. Rob Young’s Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music (2011) focused on the British folk music revival but could be understood as an auditory premonition of folk horrors to come. Young’s recent The Magic Box: Viewing Britain Through The Rectangular Window (2021) expands outside the already porous borders of the sub-genre by focusing on the intimate yet shared experience of watching the nation play out tensions between its history and future on TV. Adam Scovell’s scholarly book Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful & Things Strange (2017) journeys through the film and televisual mediascapes of folk horror using psychogeography and topography – with the writings of Mark Fisher on hauntology, ghosts and the eerie hovering nearby. British horror is Scovell’s vein, but he imports examples from abroad that distill or enrich his homegrown artefacts.

Certainly, the English countryside of the mind has proliferated beyond land’s end, finding echoes from all corners of the globe. Enter the megalithic 12-disc folk horror boxset All The Haunts Be Ours: A Compendium of Folk Horror – released this year –including the 2021 documentary, Woodlands Dark & Days Bewitched, by Canadian director Kier-La Janisse. Clocking in at three and a half hours, Woodlands and the collected films help expand the borders of folk horror – connecting the unholy trinity with similarly themed films from the same era from around the world: Kåre Bergstrøm’s Lake Of The Dead (1958) from Norway, Otakar Vávra’s Witchhammer (1970) from Czechoslovakia, Konstantin Ershov and Georgiy Kropachyov’s Soviet-era folk horror VIY (1967), Kaneto Shindo’s vampiric feline tale Kuroneko (1968), or Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964) of traditional Japanese ghost stories.

The similarity in myth and legend across different cultures is striking. It seems witches, werewolves and cursed woods are endemic worldwide. And it’s tempting to use the idea of folk horror as a universalising ethnographic tool, making us all inhabitants of a global folk horror village of anxieties built over fissures between muddy past and scalding present. But the dominant perspective of folk horror cinema is that of the outsider looking in; the camera’s angled eye making us spectators arriving in a strange land, encountering its strange inhabitants with their strange tribal rites.

The American experience – indigenous and settler – still grapples with its ancestral and colonial legacy; tremors of buried anxieties, trauma, and loss. Here, the lens of folk horror can be redirected. Folk horror doesn’t just have to be about slumbering rural landscapes and eccentrically twee village folk. Take Nia DaCosta and Jordan Peele’s Candyman (2021) reboot, which reframed the original horror franchise – a white academic researching urban myths in a Black neighbourhood of Chicago – as a story told through an African American experience. In literature, writers like Stephen Graham Jones (a member of the Blackfeet Nation) wrap the Native North American experience in horror tropes and ambiences. Jones’s The Only Good Indians (2020) uses horror to look at how lost heritage and generational divides haunt the contemporary indigenous community. The wonderfully titled My Heart Is A Chainsaw (2021) opens with two European tourists disappearing into the malignant waters of Indian Lake (at the bottom of which lurks a sunken church), slashing its brutal way deeper into folk horror landscapes, reconfiguring ‘Indian’ cliches from popular entertainment with bloody wit.

In the Woodlands documentary, Executive Director of Canada’s Indigenous Screen Office, Jesse Wente is interviewed while clips play from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), and Mary Lambert’s Pet Sematary (1989) (both originally Stephen King novels featuring Indian burial grounds): “The thing colonial states fear the most is to be colonised. It boils down to an innate fear that someone is going to come and take your home from you. And what do most Indian burial movie plots involve? Building your house over an Indian burial ground.”

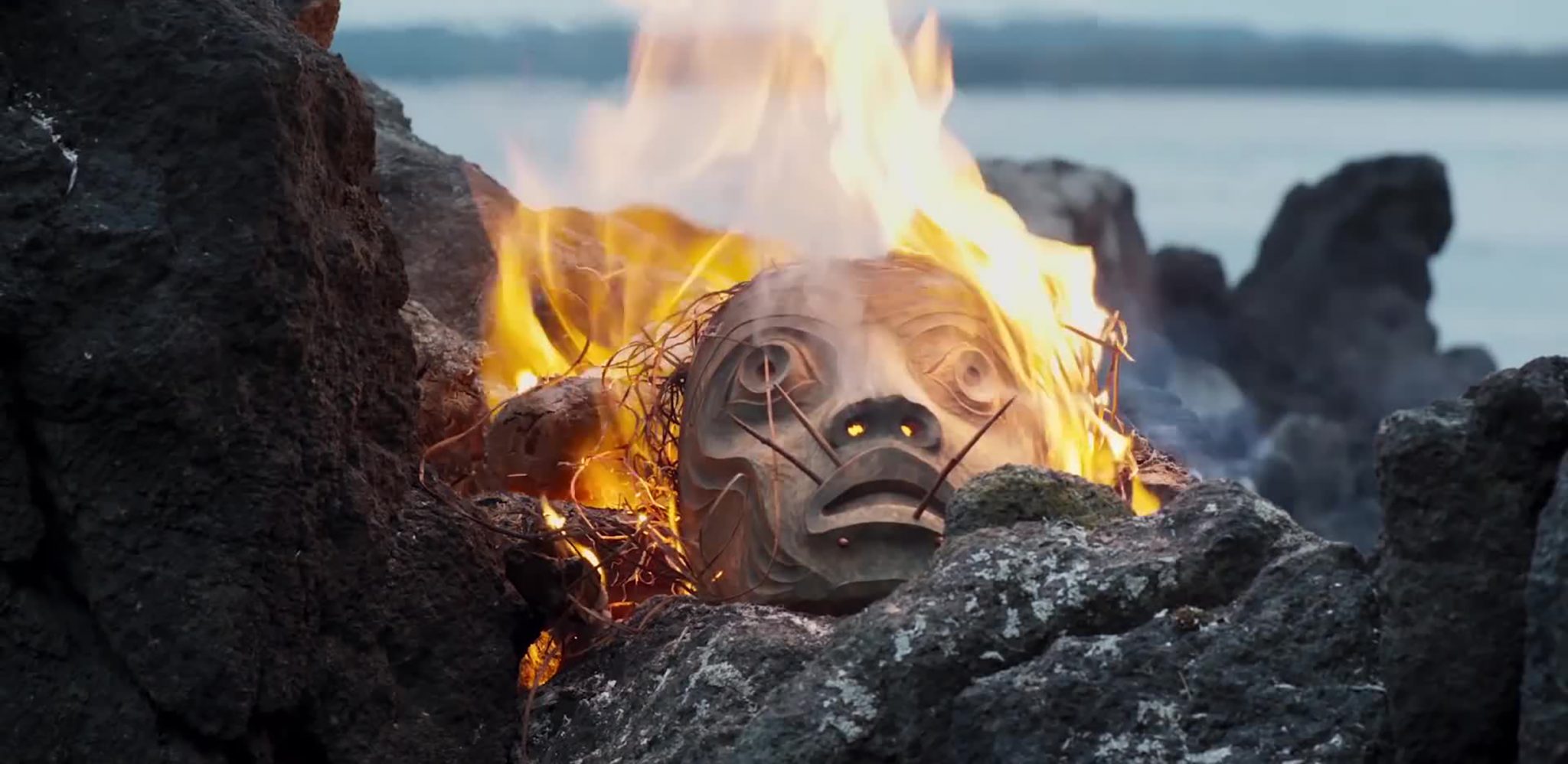

There’s a twist to Wente’s story. Cut to a scene from Gwaai Edenshaw and Helen Haig-Brown’s The Edge of the Knife (2018) of a tribal mask placed upon a fire. Set in Western Canada, it’s a traditional Haida story of an outcast man who becomes Gaagiixiid, a wild-man. Wente continues, “I sort of like it. If non-indigenous people are going to be afraid of the Indian burial ground, then I got some news for you: it’s all an Indian burial ground.” Wente’s note is all the more painful, considering the discovery earlier this year of hundreds of bodies of Native children who died in Canada’s brutal residential school system; shamed in life, murdered by ideology, buried in secret.

What is buried here, in folk horror terms, is undead: a history that is unreconciled with – no matter how deeply covered up, ignored or repressed – becomes malignant, haunts our present and pollutes our future. And, as we know from horror films, we must confront those ghosts to rid ourselves of their curse, whether by the light of day or some other ritual of exorcism. All the wondrous and cathartic clichés of folk horror help us rewrite our own relationships to history, help us call in the light of morning so we can escape our suffocating village, the ghosts in the woods, the demons in the field.

Nathaniel Budzinski is a writer who grew up on the small Pacific Northwest island where Nicolas Cage’s 2006 remake (and subsequent flop) of The Wicker Man was shot. Follow: @naterobbud