The artist’s slick evocation of precarious economic and social conditions in the digital age is tangled with contradictions

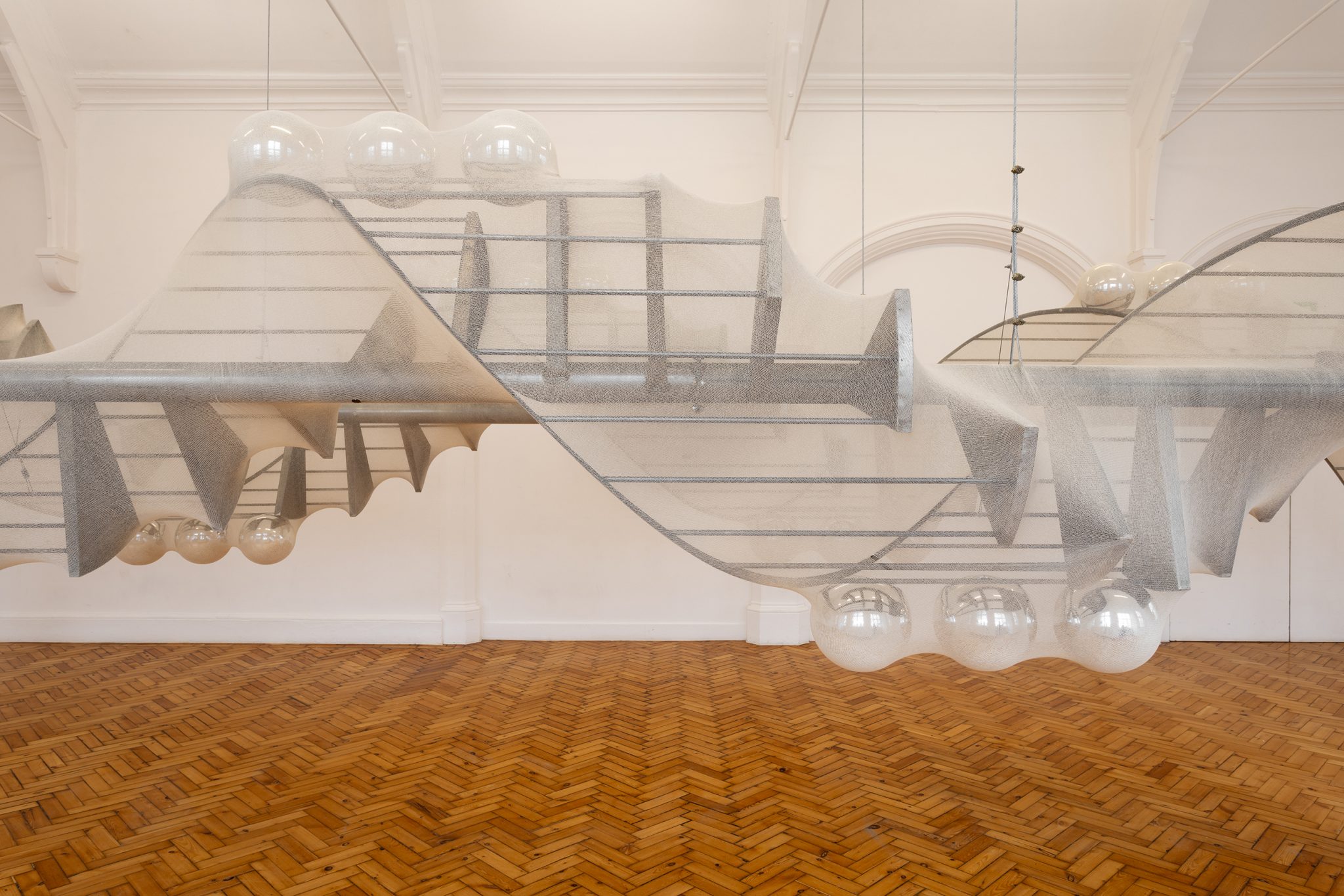

Two spiral staircases form the centrepiece of Jack O’Brien’s current exhibition The Reward at Camden Art Centre. They hang from the ceiling on their sides, winding through the air. Silver PVC balls are fixed to the railings of each steel structure in sets of three, and the two assemblages are wrapped in stretches of industrial stockinette like huge white tights, which unify the forms within and then fall into neat coils on the floor. Meanwhile, suction cups fix panes of frosted Perspex onto the gallery’s Victorian windows, cloaking viewers in soft light as they follow the spirals across the space: up and down, in and out.

In recent years, O’Brien has gained fast acclaim for sculptures that combine familiar items (clothing, instruments, cutlery, wine glasses) using simple techniques: balancing, wrapping, tying, squeezing, hanging. A flurry of shows around the world has followed his first presentation with London gallery Ginny on Frederick in 2021; his current exhibition comes off the back of the Camden Art Centre Emerging Artist Prize, which he won last year for his display at Frieze London. Discussions of the artist’s work so far have tended to read it through his experiences as a gay man coming of age in twenty-first-century London. They have followed his own insistence that his practice ‘considers the fraught nature of my social, economic and sexual experiences’. In particular, his tactile manipulation of materials is said to emerge from the city’s cruising grounds and sex parties: critic Caroline Elbaor claims he ‘depicts… the tug-of-war in desire’, making work ‘laden with sexual connotations’, while in the exhibition booklet at Camden Art Centre, the art historian Dominic Johnson finds ‘something hazily erotic’ in the ‘relation between the tightly sheathed phallic object and its spent, drooping excess’.

O’Brien is not undeserving of his newfound attention, but the fixation on the supposed eroticism of his work has distracted from its precise formal quality and significance. In a 1967 essay titled ‘Eros Presumptive’, art critic Lucy Lippard explored the erotic potential of nonfigurative sculpture, arguing that the ‘sensuous element’ can be ‘heightened’ in abstract art because it is not ‘submerged in anecdote or decoration within a representational context’. In O’Brien’s work, though, sex is not evoked through form but represented with details too literal to produce a visceral impact: nipple-shaped suction cups, rails pressed into bulging spheres, stockings ripped and strewn on the floor.

The Reward lacks the sense of tension and mystery – the messy complexities and confrontations with difference – that are often central to arousal and intimacy. The two staircases are identical, down to the orderly positioning of the chrome balls, and they hang perfectly parallel to the floor and each other, as if weightless. Their construction, meanwhile, can be understood at a glance: the wrappings are translucent, the technical manipulations minimal and the materials simple, even mundane. Nothing here is hidden or unknowable. There is nothing more to desire, no interior space or anticipated moment of release, and no sense of instability: no risk that the cords could snap, that we could be crushed, violated or achieve ecstasy. This impression is corroborated by contradictions in Johnson’s essay; he quotes O’Brien’s celebration of the ‘electrifying sense of the unknown’ that characterises cruising, while elsewhere describing the artist’s materials as ‘recognisable or accessible to the viewer’ and his techniques ‘self-evident’. How something can both evoke a sense of the unknown and embody ‘democratic legibility’ is unclear.

Despite his focus on the eroticism of the work, Johnson pinpoints its formal quality when he describes it as ‘disconcertingly remote’. O’Brien’s considerable skill as a sculptor is in making materials appear immaterial, using this intensely physical medium to produce experiences of unnerving virtuality. His gestures – turning the staircases on their side, hanging them from the ceiling, wrapping them in fabric – work to untether the structures from the ground and obscure their relation to the body. Each action removes the objects both from the space of the viewer and their original function. So they acquire a ghostly quality, as if they are holographic illusions, somehow not really there. In this sense, they recall the slick cynicism of Jeff Koons, silver balls and all, over the libidinal angst of Giacometti’s early surrealist objects. Viewers expecting flesh and blood are confronted with only cold surfaces. This process, of intimacy promised and denied, seems reflective of the crisis of sex in contemporary culture, of arousal reduced to a marketing tool and digital technologies that sell false dreams of instant connection.

That same transitory sense of remoteness in O’Brien’s work is suggested by his 2023 sculpture Volent – a nineteenth-century carriage wrapped in a dense web of cellophane. The cart – a simple container with two large wheels – is defined by emptiness and mobility, even if its aged surface lends it a whiff of olde authenticity. By packaging what is in a sense already a piece of packaging, inspired by the sight of goods wrapped up on pallets, O’Brien produces an icon of nothing but concealment and commerce. The main component of his prizewinning display at Frieze London last year, Volent parodies the status of artworks in the global market: empty vessels of exchange value, shallow illusions of authenticity – that move between art fairs and tax-free warehouses, often never leaving their crates.

In his 1996 essay ‘Sculpture: Publicity and the Poverty of Experience’, art historian Benjamin Buchloh traced correlations between socioeconomic conditions and approaches to found objects. Postwar artists like Claes Oldenburg and Arman presented large ‘accumulations’ of similar artefacts and employed an ‘aesthetic of the showcase’, reflecting, in Buchloh’s view, the erosion of historical consciousness and use value by consumer culture. Such work is a far cry from the attitudes of interwar Surrealists André Breton and Joseph Cornell, who treasured old things as stores of overlooked potential and historical memory. When compared with sculpture’s origins in public monuments, it becomes ‘evidence about the disappearance’ at the hands of commodification ‘of the last vestiges of social interaction in the residually existing forms of public space’.

O’Brien’s practice exemplifies a further stage of the development Buchloh describes – in which materiality and history are supplanted by a virtual space of circulating commodities – by transforming tangible artefacts into ethereal illusions or ghostly reproductions. This is epitomised by the spiral staircases: while inspired by structures situated outside O’Brien’s old South London studio in a former factory, an allusion to a fading industrial landscape, the examples in The Reward are not in fact found objects but were fabricated by a staircase manufacturer for the exhibition. Even the very recent past, it seems, is inaccessible as anything other than an image. Doubt, 2024, also on display in Camden, allegorises this process. The horn of a trumpet is affixed by its opening to a wall, forming an elegant stem out of which grows an arrangement of old silver forks knitted together by their prongs. A single pane of Perspex sits precariously at the front of this intricate assemblage so that all these storied objects, elaborately intertwined, become a mere mount for an anticlimactic rectangle – flat and empty.

If Arman’s accumulations of artefacts as commodities resulted from postwar consumerism, what current conditions might be responsible for O’Brien’s transformation of historical objects into slick, holographic visions? A provisional answer is suggested by two seemingly disparate facts: first, that the artist has described the need for his work ‘to be collapsible’ and ‘easy to move’ because of extortionate and precarious rental arrangements; and secondly, that the work’s sheen and apparent weightlessness look particularly dramatic in photographs. The sculptures are symptomatic of a degraded and vicissitudinous physical environment: of temporary studios in rapidly developing neighbourhoods, flimsy art fair booths, hidden storage facilities and, perhaps most significantly of all, the consumption of art through screens. These are compounded factors that render material integrity and groundedness – in a specific time and place – not only impossible but, from a commercial perspective, undesirable. If O’Brien’s work is to be understood in erotic terms, then it is more internet porn than sex with strangers in a park; more lonely doom scroll than sweaty embrace.

Jack O’Brien: The Reward at Camden Art Centre, London, through 29 December

Michael Kurtz is a writer based in London