In the artist’s drawings, shown at Bosse & Baum, London, fragments of the body merge uncomfortably with dreamy landscapes

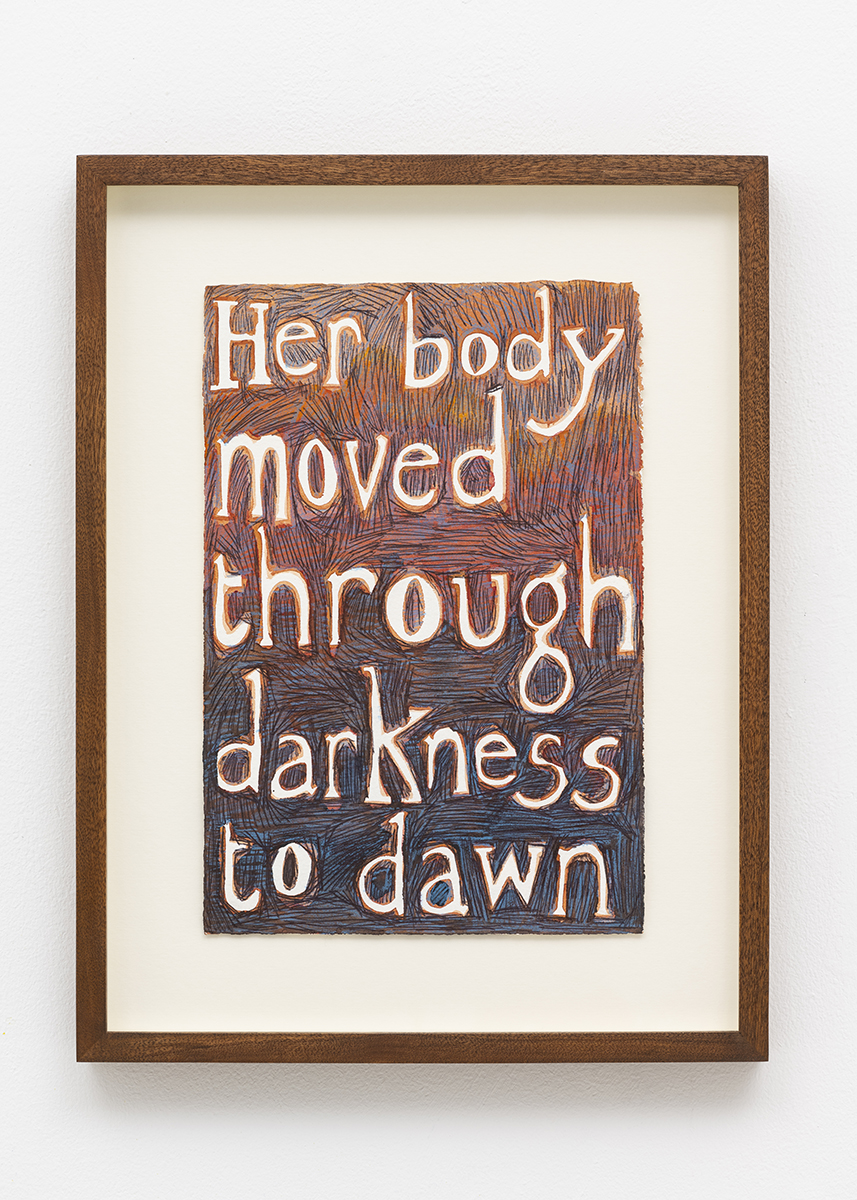

pencil crayon, highlighter pen, ink, graphite on paper, 42 × 33 cm. Photo: Damian Griffiths. Courtesy the artist and Bosse & Baum, London

Navigating the affective ambiguities of bodily consciousness, often through the prism of Afro-diasporic subjectivity, Jade Montserrat’s drawings resist clear-cut interpretation. In them, fragments of the body merge uncomfortably with dreamy landscapes, strewn with motifs that feel symbolic but whose meanings could be multiple and conflicting: a hand-shaped rock reaching out of the ocean (In Tune with the Infinite, 2015); a pair of feet with vultures perched on its toes and heels, while scattered over its pinkish skin are blue-and-yellow round bushy growths, possibly sea anemones, and diamantine shards (Feet, Spectator, 2016). The recurring motif of the groin, presented as a frontal, semicartographic outline from waist to thigh, may celebrate female sexuality as a source of strength, and yet combined with such utopianism are more discomfiting references to sexual objectification and bodily dispossession. In Torso: Reef-knot (2020–21), the joyous palette (blue sky, pink blossoms), the balletic effect of the white zigzags and even the fantastic octopus-shaped ‘hair’ covering the figure’s genitalia are superficially uplifting. But less so are the potential allusions to the Middle Passage in the reef knots and the gold cage-like material cladding the Black skin.

39 x 30cm. Photo: Damian Griffiths. Courtesy the artist and Bosse & Baum, London

Text is often incorporated into the images, many of the phrases starting with the words ‘Her body…’, which act as the exhibition’s verbal refrain. But despite the possessive pronoun, self-possession is never stable. That the meaning of these phrases – and by extension most of the works in the show – is unfixed is suggested by the precariousness in Montserrat’s rendering of the letters, as if they were in a state of frenzied motion or competing for visibility with their surrounds. In Her body moved through darkness to dawn (2017–21), the words of the title shiver amidst red-and-pink cellular forms floating in ultramarine; against the white letters, brown spawnlike cells also appear to be growing. The work elicits both hope and suffering, as we’re unsure of how to read ‘darkness’ or how her body came to understand its meaning. Perhaps Montserrat is telling us to hold off interpretation, just for a moment, and find a middle way between reading, looking and feeling.

Jade Montserrat: In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens at Bosse & Baum, London, 5 June – 24 July

From the September 2021 issue of ArtReview