The artist’s multimedia process of manipulation – on show at Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles – destabilises any cohesive understanding of the artistic tradition

James Chronister doesn’t paint landscapes. Well, not traditionally speaking. His richly detailed greyscale paintings sidestep expectations: absent are the sentimental vistas of yore, the Romantic visions of untouched land. Instead, this Montana-based artist depicts closeup fragments of densely forested scenery to investigate the boundaries between the organic and the artificial. Heavily altered photographs of local environments serve as the source material for Chronister’s photorealist paintings, which feature overwhelming arrays of plant life cast in ghostly, unnatural hues. Chronister negotiates earthly abundance within the limits of its representation: his use of analogue and digital techniques further warps these compressed, fractured views, disrupting a genre marked by soothing illustrations of wilderness.

Chronister represents a claustrophobic, all-consuming natural world. These works defy conventions of landscape painting that typically imagine the artist removed from his surroundings, staring out at carefully encapsulated scenery. In contrast, Saudade (2021) positions the viewer both above and below layers of thick underbrush, confusing perceptions of depth: trees appear simultaneously distant and near, their actual size made incomprehensible. In Summer Spell (2023) Chronister tricks the eye into following two-point perspectival lines along a pair of fallen logs; a swarm of crisscrossed branches quickly halts this Renaissance technique, stranding the viewer mid-frame. Where nineteenth-century painters like Caspar David Friedrich or those of the American Hudson River School privileged totalising representations of nature, these artworks imagine the environment – not the artist – as a conquering force, one that easily overpowers attempts to capture it in its entirety.

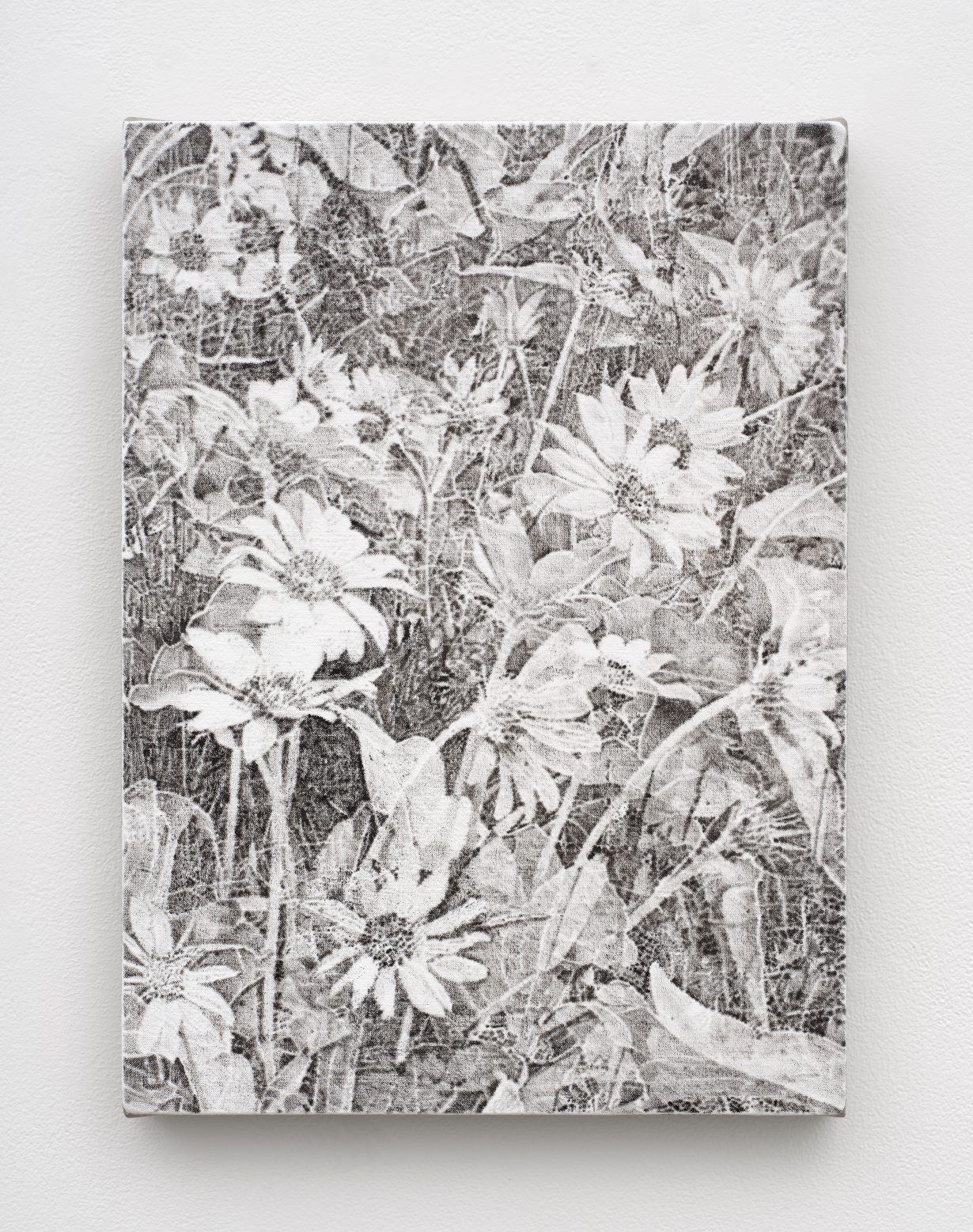

Chronister’s multimedia process – the artist begins with photographs, manipulates them digitally, then paints – destabilises any cohesive understanding of his landscapes. At first glance, each painting resembles a matt print of a highly photoshopped image: in Fine Time (2023) a lone dandelion sits overexposed in the frame’s centre, the surrounding flora reduced to a colour spectrum of greys, whites and blacks. A closer look reveals Chronister’s illusory technique, where the artist’s meticulous stippling makes his brushstrokes nearly invisible. Chronister’s paintings evoke a lasting discomfort, an unease created by the inability to discern the artist’s medium: in I remember.. (3) (2023) a mass of daisies and grass recalls the flattened impression of a screenprint or cyanotype – not the multidimensional plane common to photorealism. The artist’s multistep method presents a world that is both manmade and not, disturbing the passive spectatorship offered by his predecessors.

It is rare to encounter artworks that feel as complex from afar as they do up close. These paintings operate like logic puzzles: it is impossible to decide whether they are more real than artificial, more natural than human. In an era that often calls for artists – especially artists working with landscape – to be de facto environmentalists, Chronister accomplishes a deft critique. Nature, here, is not reduced to symbol or argument; it does not serve to enlighten the human experience or testify to its supremacy. What lingers is Chronister’s formal and ideological precision, a rigour that renders earth as it truly is: beyond comprehension.

All the faces we know, all the / places to go / Shall we stop to say hellos? at Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles, through 26 August