“I’m interested in both sides of the line of language,” Jean-Luc Moulène told Tate’s Chris Dercon during an interview at Modern Art Oxford last year. Poetry lay on one side, he said, mathematics on the other. “But I think art could be both,” added the Reims-born artist, “because it’s not language.” Remember that when confronting Moulène’s practice, which is formally ambulatory, somehow both clear and opaque, and consequently knotty. Literally so in his Blown Knot (2012) series of glass objects, produced during a residency at CIRVA, the Marseilles research centre for art and glassmaking. Bulbous blown forms in three colours (red, yellow and blue), wrapped complexly around each other and interfusing, these are at once deliriously aesthetic things – you can follow their soft transparent tunnels and glowing interplay of secondaries and tertiaries for a long time without getting bored – and the showy yields of applied physics.

Moulène enjoys this doubling-up, his artworks often feeling like traps for the empirical and open-ended alike. A series of mirrors, placed near corners and accompanied by swatches of colourful Lycra pinned tightly by its own corners where the walls meet, are both informative (here’s what a part of the world, ie you, looks like; here’s what material under multidirectional stress looks like) and amorphous, for what’s the relation between you and this colour? Five photographs taken in New York in 2012 – a tree, the interior of the Strand bookshop, a pretty girl toting a mobile phone, foodstuffs laid out on Chinese newsprint, a half-blackened building whose burned frontage and plywood-blocked windows make the image look semisolarised – are locally informative yet don’t add up to a worldview. As the handout points out, they reenact classic pictorial strategies (still life, landscape, portrait), but they’re highly specific. A categorical form meets an emblem of the world’s irreducible variety, even as found in just one city.

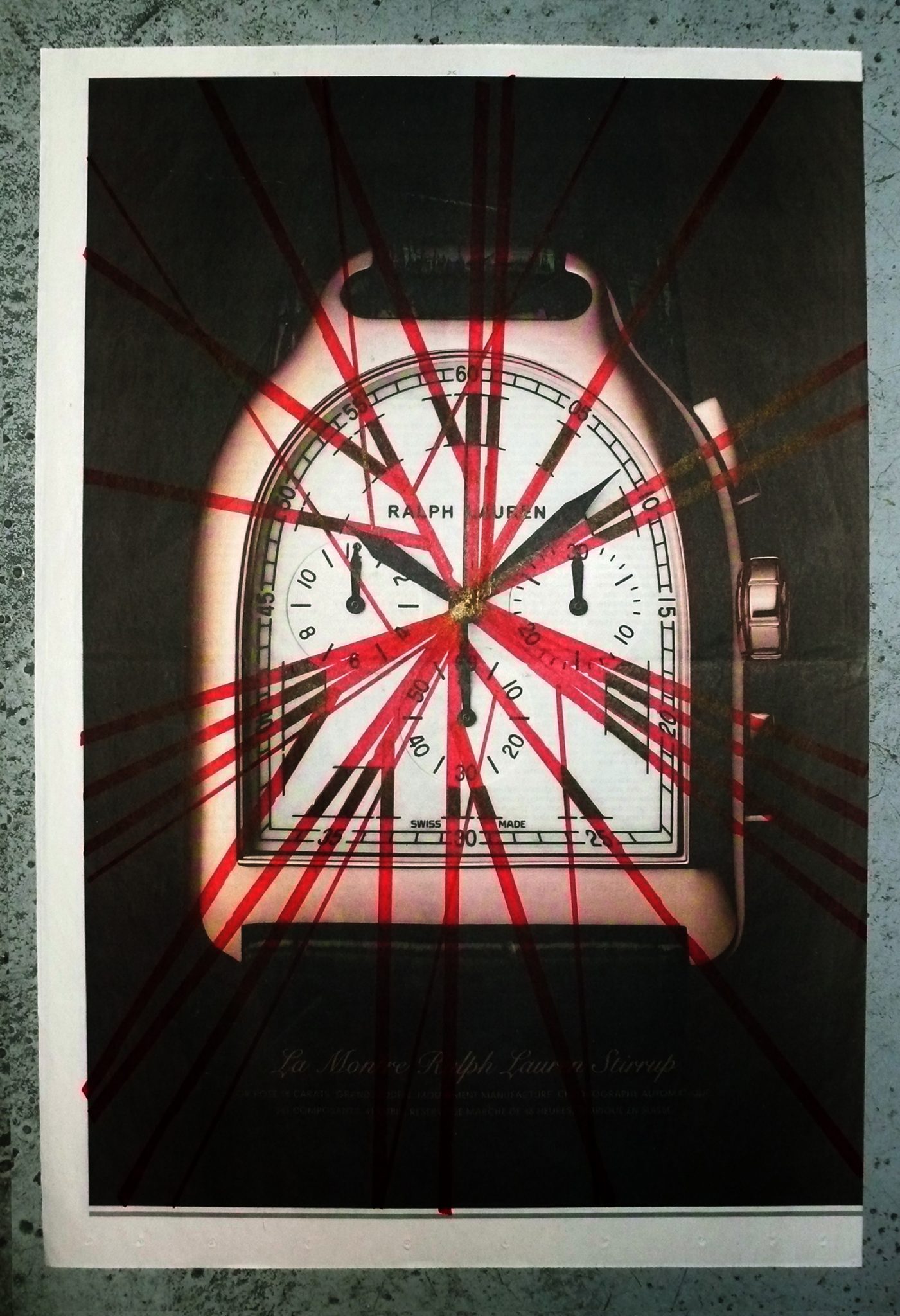

For his previous show here, in 2007, Moulène exhibited Products of Palestine (2002–4), photographs of 58 consumer products that, due to sanctions, never leave the Gaza Strip and West Bank. That’s as loaded a subject as you might find, but it’s also a metaphor for circulation. The objects can’t move, but an image of them can. Seemingly fixed things can move in diverse ways (here’s where glass and stretchy material meet on the metaphoric plane): in the imagination, for example. So Moulène’s two tastefully defaced advertisements for high-end watches, one from Le Monde and the other from The New York Times, both titled Ralph Lauren’s (2012) – spokes in black or red felt tip pen radiating outward from pictured clockfaces – are at once comprehensible and suggest an attitude to luxury goods. Nearby, meanwhile, is Trou d’ A380 (2012), a model aeroplane retrofitted with bars erupting from the wings; from the crossbar dangles a vaguely noose-shaped twist of green wire. None of these works are exactly indicting; they foxtrot around critique, suggesting but not reifying an attitude to the thing modified.

If there’s a model here for that equalising of prompt and constraint, it’s Moulène’s pair of iron birdcages, each filled by a glass object fitted near-perfectly to its dimensions, bubbling outward through the open cage door and the circular aperture at the top. The technics involved in fabricating such things make the brain hurt to contemplate, and they’re emphatically part of the work. But everything else about For Birds 1 and 2 (2012) resides, tantalisingly, on the other side of ‘the line of language’.

This article was first published in the January & February 2013 issue.