The UK political establishment still sees the housing market as a reliable source of trickle-down prosperity for all. Others see an engine for social cleansing. To paraphrase the press release for Laura Oldfield Ford’s Seroxat, Smirnoff, THC, the obsession with private ownership has created new social demarcations, bankers billeted in ‘Zones of Refuge’ and zero-hours contract workers exiled to the ungentrified ‘pogroms’ of Catford and Streatham, the ‘Zones of Sacrifice’. “The idea of a collective space is there,” she says in Pray for Love (all works 2014), a 25-minute audio piece listened to on headphones. “But surely one could do it better.”

A typical Oldfield Ford painting depicts youngish figures in downbeat municipal contexts, council flats or abandoned modernist buildings. These ciphers of the ‘melancholic left’ stare glassily into the middle distance, surrounded by handwritten text, musings on the character of suburban England, whose shifting social sands the artist has chronicled in her Savage Messiah blog for nearly a decade. The works made during her recent Stanley Picker Fellowship both consolidate and expand this format, with language given a new primacy. The paintings have a seductive, dissipating warmth, the cool pink ground showing through the drab architecture like the embers of a coal fire at dawn. Deal or No Deal (4+1 Edmunds Heirophant) shows two men and a woman in a spartan interior, the bare mattress suggesting a squat, nostalgic reflections hovering around them in white capitals: INTO TOWN CENTRE, BLEACHED WHITE IN THE NEAT PEDESTRIANISED ZONE + TREATY CENTRE WHERE ROBBO WORKED

AS FATHER CHRISTMAS 1992. The protagonists look too young to own these memories; if the words caption the image, they do so in terms that Barthes might have called ‘relay’ rather than ‘anchorage’, diverting your thoughts elsewhere.

Effectively, language is a rejoinder to the sovereignty of the painted image, lest it be seen to draw aesthetic consolation from the political status quo. Though not an explicit critique of the neoliberal hegemony ushered in by New Labour and fortified by the Bullingdon Club, the entire atmosphere of Oldfield Ford’s work is shaped by its social divisiveness. Her militant contempt for the beneficiaries can make her sound like a character from a late J.G. Ballard novel, a hoodlum psychogeographer glowering at the smug fauxhemia of Patisserie Valerie. Untitled, a freestanding MDF billboard, dispenses with painting altogether, using printed images of flowers and a woman drinking wine as a backdrop for a handwritten rant against ‘networked leisure provision for yummie-mummies’ and ‘the rattling concerns of mumsnet’. The phrasemaking feels fresh, disparate phenomena yoked together into lists that have a peregrinatory rhythm, perhaps subconsciously metered by the writer’s own footfall as she paces the pavement.

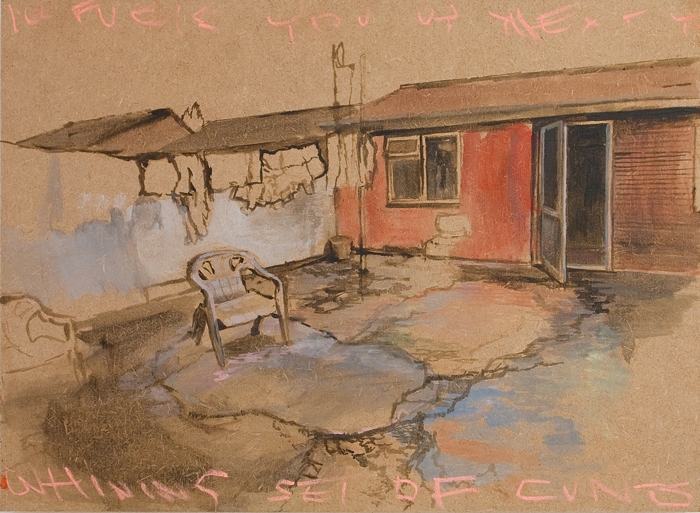

Maybe there’s room to experiment with how word and image are combined. I wondered about the possibility of embedding text within the pictorial space rather than emblazoning it across the surface – which risks promoting language to a countermanding rather than countervailing force. I kept returning to the small oil sketch A132 Hounslow, a view into a mouldering garden, bungalow in the background, washing line and white plastic chair in the foreground, the words I’LL FUCK YOU UP NEXT TIME YOU WHINING SET OF CUNTS chalked on the image. The utterance matches the mood of the painting, both texturally and semantically, the hurriedness of the hand-writing and its sentiments echoing the expedient technique. In the other paintings, an omniscient speaker cuts across them, whereas here the verbal and pictorial are interlaced, the voice in character.

This article was first published in the January & February 2015 issue.