The first Dragon Hill X ArtReview Writers Residency text discusses Jean Cocteau, the morality of beauty and art’s necessary isolation from the daily turmoil and churn of politics

Over the course of 2024, six art and culture writers selected by ArtReview have been joining groups of visual artists selected by London’s Unit gallery on a residency at Dragon Hill in Mougins, near Nice. This historic home, designed and built in 1964 by Jacques Couëlle, is set in a private domain that has counted Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Yves Klein, Yves Saint Laurent and Leo Castelli among its residents. Some of the writers on this residency have written previously for ArtReview, others have not; some of the artists are represented by Unit, others not.

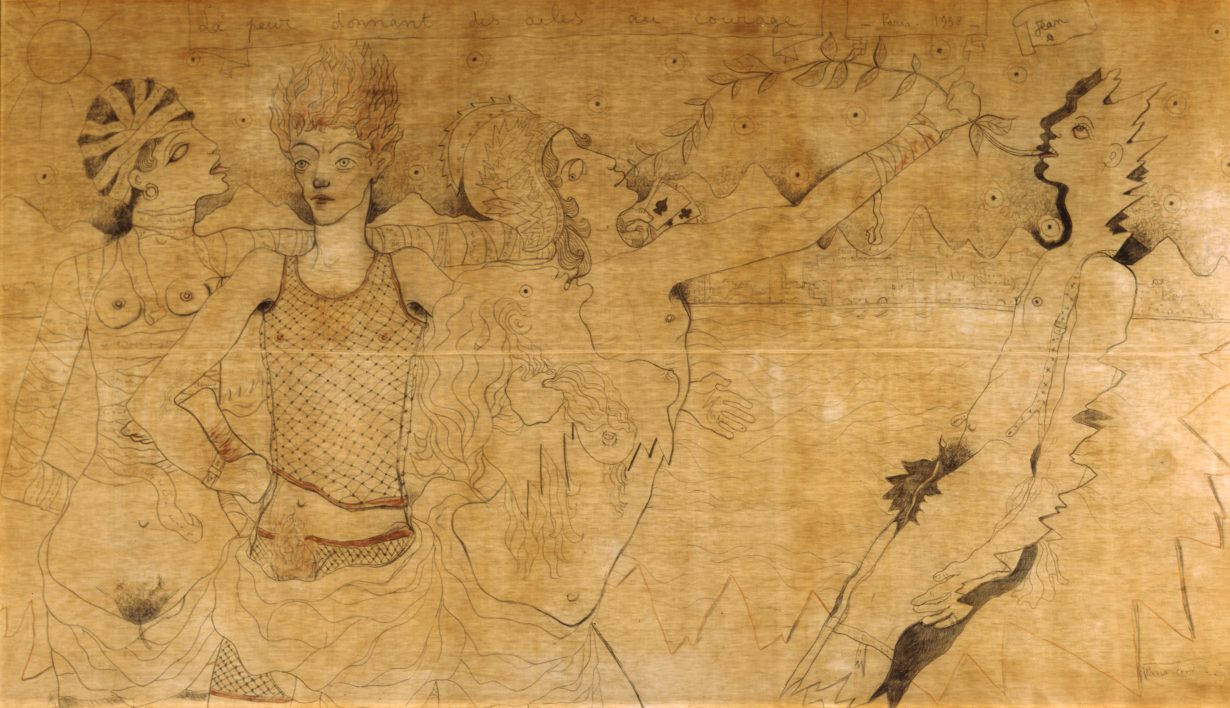

The first resident, London-based writer and editor Lydia Figes, lived at Dragon Hill in May and early June. She has written a text on the subject of beauty, and specifically art’s necessary isolation from the daily turmoil and churn of politics, violent conflict or even a moral consciousness, as expressed by Jean Cocteau in his short collection of writings Secrets de Beauté, first published in 1945 and republished this year in a translation by Juliet Powys.

The decision to turn away from politics – towards an aesthetic, poetic life – prompts an age-old debate: in times of crisis, what is the moral responsibility of the artist? In March 1945, Jean Cocteau’s car broke down en route to visiting his lover, the actor, director, painter and sculptor Jean Marais. Abandoning the vehicle for a Paris-bound train, Cocteau, himself an artistic polymath, grabbed any scraps of paper he could find and began writing. This is the context in which Secrets de Beauté (1945), a collection of ruminations and aphorisms, the inspired musings of a man who shamelessly lived a poetic life – one bridging the imaginary and tangible, the mythical and real – began life. That life continues in a new English translation, Secrets of Beauty, translated by Juliet Powys and published earlier this year, in a reminder that the pursuit of beauty during times of immense conflict raises moral questions that unsurprisingly continue to play out in the present day.

Known for his abundant creative energy, Cocteau spent the final months of the Second World War writing compulsively, albeit questioning his subconscious motives. ‘Why do these thoughts come to me, to someone who is so reluctant to write?’ he scribbles, perhaps disingenuously, on the impromptu train journey. ‘It’s probably because… I am writing them on the move, in a third-class carriage that keeps jogging me. I reconnect with this dear work [of writing] on the endpapers of books, on the backs of envelopes, on tablecloths: a marvelous discomfort that stimulates the mind.’

By the time Cocteau wrote Secrets of Beauty, he had already built a successful yet somewhat controversial career, one spanning poetry, literature, the visual arts, opera and even experimental film. He’d also picked up a reputation for an opium addiction and for his bisexuality. As the war drew to a close he turned his attention once again to poetry and cinema, releasing his fantastical 1946 masterpiece, Beauty and the Beast (starring Marais), shortly after publication of the first edition of Secrets de Beauté, a title he had first used for an article written for the cultural journal Comoedia in 1943.

During the entirety of the German occupation Cocteau remained in Paris, neither explicitly opposing the Nazi-supporting Vichy regime nor joining the Resistance. And although he presented himself as apolitical, he nevertheless befriended certain individuals with right-leaning tendencies, including the Nazi sympathising sculptor Arno Breker and his lover Marais. ‘A poet must concern himself with poetry alone,’ he asserts in Secrets of Beauty, writing from a cramped train carriage rolling through the French countryside. ‘Beauty hates ideas. It is sufficient to itself. A work of art is beautiful just as a person is beautiful. The beauty I speak of provokes an erection in the soul. One cannot argue with an erection.’

But what does it mean for the poet or artist to turn away from reality? Unlike his contemporaries Pablo Picasso, who veered towards political art during the Spanish Civil War, creating Guernica in 1937, or Max Ernst, who painted Europe after the Rain II between 1940 and 1942, Cocteau’s art remained resolutely detached from current affairs. His reluctance to join artistic cohorts and movements – underpinning his constant juggling act of creative expression – ultimately served to undermine his reputation during his lifetime and perhaps too posthumously. Cocteau was criticised as capricious, tagged with the nickname ‘coq-a-l’ane’, meaning to change the subject abruptly, or to be all over the place. Dismissed as a dilettante; a jack-of-all-trades and master of none, he flitted between European avant-garde groups, all of whom grew exasperated with his lack of commitment to any movement or manifesto, and attracting, among other reasons, the disapproval of the Surrealist leader André Breton. His friend, the writer François Mauriac, characterised him somewhat disparagingly as an “ubiquitist”.

Yet in Secrets of Beauty, we sense that Cocteau is grappling with his own resistance to notions that he should conform to expectations. It almost reads as a defence of the solitary, creative act itself, one upholding art for art’s sake. Undoubtedly, it was also his neutrality and apoliticism that served him poorly in posterity, especially in the postwar context of thinkers such as Theodor Adorno, who famously pronounced that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”. Yet Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory (1970), in which he later investigated whether art could genuinely transform society, also concludes that true art – embracing the contradictory forces and interpretations – must at least appear to be autonomous from modern society, and therefore not beholden to everyday politics.

Cocteau’s naval-gazing (with the underlying question being: why do I write?) lies at the heart of Secrets of Beauty, which is not merely about disclosing his artistic secrets, but about legitimising the struggle and life of the artist – the decision to escape into the imaginary, into an uninhibited realm of possibility beyond moralism or didacticism. Like the Ancient Greeks, he illustrates creativity as omnipotent and mythical; an external entity that overwhelms the mere mortal (“The poet is a servant of forces that he does not understand,” he writes). On the one hand, Cocteau viewed himself as a kind of martyr of the inexplicable forces of the universe, but also as a soldier in combat with creativity. “The canvas hates to be painted. The colours hate serving the painter, the paper hates the poem, and the ink hates us. What remains of these struggles is a battlefield, a famous date, a hero’s testimony.”

To reread Secrets of Beauty helps ascertain why Cocteau was disliked by many of his contemporaries, yet also why he was misunderstood during his life. Perceived as forever sleepwalking through life, he was in fact, on the weight of evidence here especially, propelled by instinctual, creative impulses rather than the politics of the day or a moral consciousness. For all his disdain for reality, Cocteau believed that the liberated poetic act – unencumbered by rules and limitations – is in and of itself political. Its power lies in its very futility and absurdity – its opposition to the everyday. And ironically, Adorno was himself partial to this notion, concluding “insofar as a social function can be predicated for artworks, it is their functionlessness”.

For all of the accusations that Cocteau’s art reflects his shallow whims, he understood the need for art to stand outside of the everyday. “Poets who get involved in politics find themselves led astray in what is moribund in comparison to the era in which they really live. They risk being dragged down into death,” he wrote: art must separate itself from suffering and the everyday to stay alive. In this sense, art and beauty remain forces unto themselves, embodying hope and offering an antidote to death.

Jean Cocteau, Secrets of Beauty (2024), translated by Juliet Powys, is published by Eris. Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge is on view at Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, through 16 September

Lydia Figes is a writer and editor based in London