The Contractor finds the artist burnt out, ambivalent, showing up for work because there’s a job to be done and kids to feed

Jesse Darling’s exhibition The Contractor is accompanied by an eponymous text, authored by the artist and speaking about himself in the third person. ‘The contractor is here in the city with a job to do,’ it begins, foregrounding that making art is labour like anything else, its makers subject to alienation effects. If it’s particularly difficult to justify artmaking, which ‘only serves to reinforce a war machine’, amid the daylit nightmare of the 2025 news cycle, this contractor will nevertheless do it anyway, because ‘there are kids to feed’ and, perhaps, by now – though Darling has in the past publicly mooted quitting art – they’ve nowhere else to go. The tone is one of pragmatic workaday resignation, near-burnout meeting determination and resulting in deep ambivalence. The gallery’s storefront window is half-covered with a sea of painted vertical marks and diagonal strikethroughs, like a prisoner’s daily wall markings. There have, these numberless glyphs suggest, been many days like this one to struggle through, and there’ll be more.

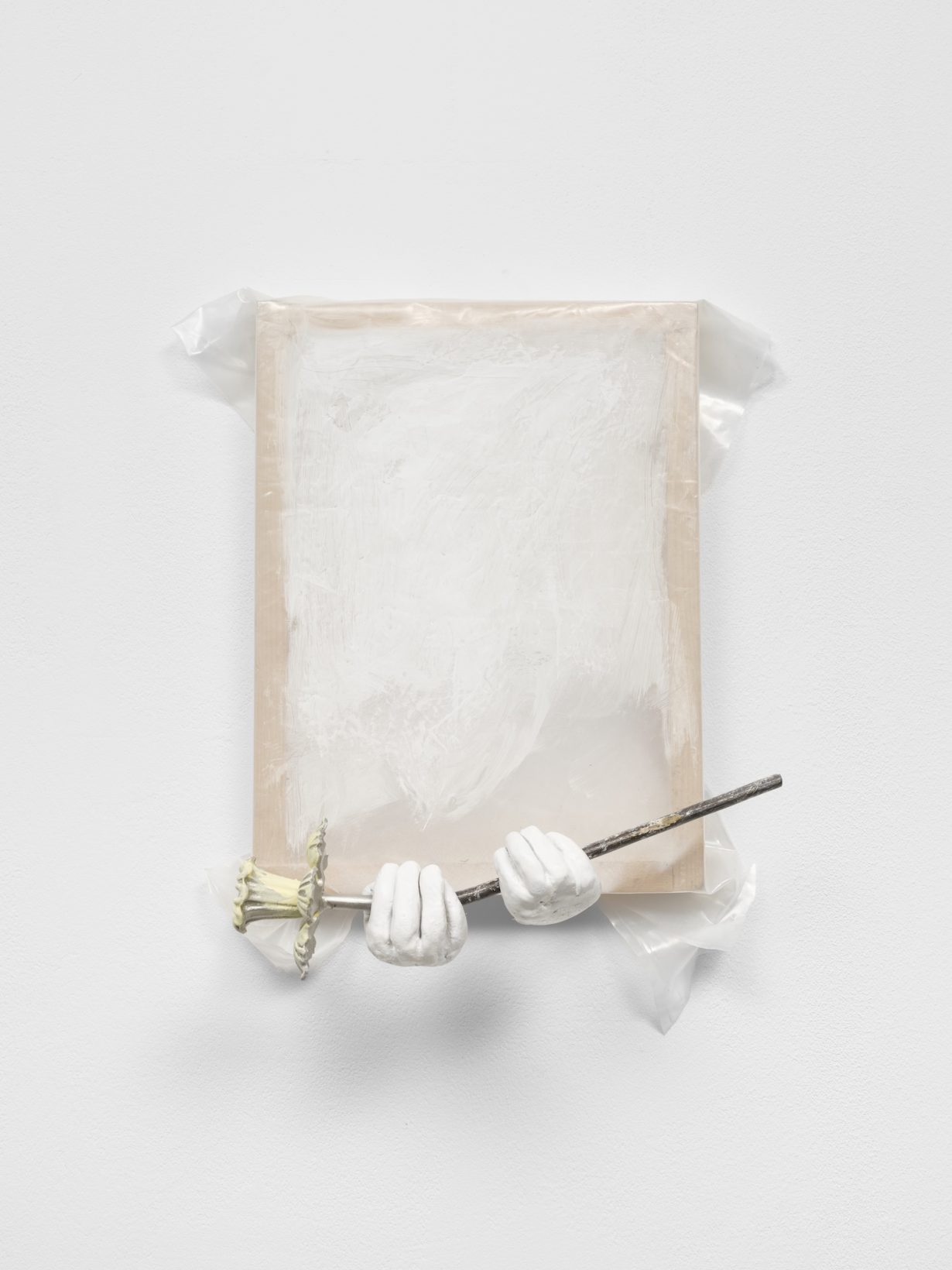

The chief risk of this framing is that the artworks themselves could be seen as an afterthought, that it doesn’t really matter what they are. But the inclusions are frequently slippery enough to sidestep that. Some do refer directly to labour and financial matters: the wall-mounted assemblage Contractor I (all works but one 2025), one of several works infused with a Funk-art flavour, wraps a ragged hessian moneybag like a shawl around an olive-green welding helmet, topping it off with a decorous metallic filigree of leaves. Das Wirtschaftswunder II, which refuses definition as either a painting or a sculpture – translucent plastic loosely wrapped around a stretcher is daubed with white, while a pair of outstretched hands in white plaster protrude from the lower edge, gripping the stem of a metal daffodil – is titled after the West German ‘economic miracle’ of the 1950s and 60s. Other pieces ostensibly revolve around notions of home and family but bend their signifiers aslant. The luminously pastel-toned, pencil-and-acrylic drawing Die Familie, on a framed scrap of crumpled paper, lines up a female, male and two gender-ambiguous, genital-free figures – one leaning on a bent crutch, a longtime Darling shorthand for damage and support – all nude, heads covered in baglike hoods, and against a background battalion of doodled pointed-roof houses that double as upward-pointing arrows. The results land somewhere between warped cabaret and photos from Abu Ghraib, with the one thing clear about the embattled quartet being that they’re in this together.

The chief flavour of such work, with its knotty tangling of iconographies, is a kind of pithy obduracy: you’re compelled into looking, but at what you’re not entirely sure. That’s a quality inherent even in signature-style pieces like Epistemologies (Amtsschimmel) (2018/25), a vitrined trio of administrative ring-binders containing not pages but blocks of concrete the size of a ream of A4; and mechanical sculptures like Der Ordoliberalismus (Home), an open-sided wooden box crowned with a doll’s-house window that rotates, while a pair of fists poke combatively from the work’s base. Things you can’t read, things functioning without apparent motive, things that want to punch back, a preponderance of masks: Darling seems to be addressing, in formally diverse ways, how you give and withhold at once, contract yourself out but shelter your soul. If The Contractor, accordingly, frequently feels slightly out of reach, that may be not a bug but a feature.

The Contractor at Molitor, Berlin, through 8 November

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next “I think about modernity as a fairytale”, Jesse Darling tells Louisa Elderton