In 2019, after a decade-long break from making music, Johanna Hedva released the album The Sun and the Moon, a black slurry of rich, harsh noise, industrial beats and grainy samples. They describe this music as ‘Hag Blues’ made ‘for those who feel best in caves’. One song repeats the phrase “Man, beauty is so fucking dumb, the fuck” for minutes. Like much of Hedva’s work, the album is a celebration of darkness, an evocation of the swampy zone where the sacred and profane meet.

Hedva’s upcoming album, Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House, is radically different in technique though similarly thick in its mood, a lugubrious fuzz of doom guitars and vocal aching in the form of a eulogy for their mother. “In one song”, Hedva says, “I feel like I am death itself, in others I am my mother, encountering it.” To convey this, Hedva has studied operatic and Korean pansori singing styles as a way of expressing the binary quality of their Korean- European identity through a single throat.

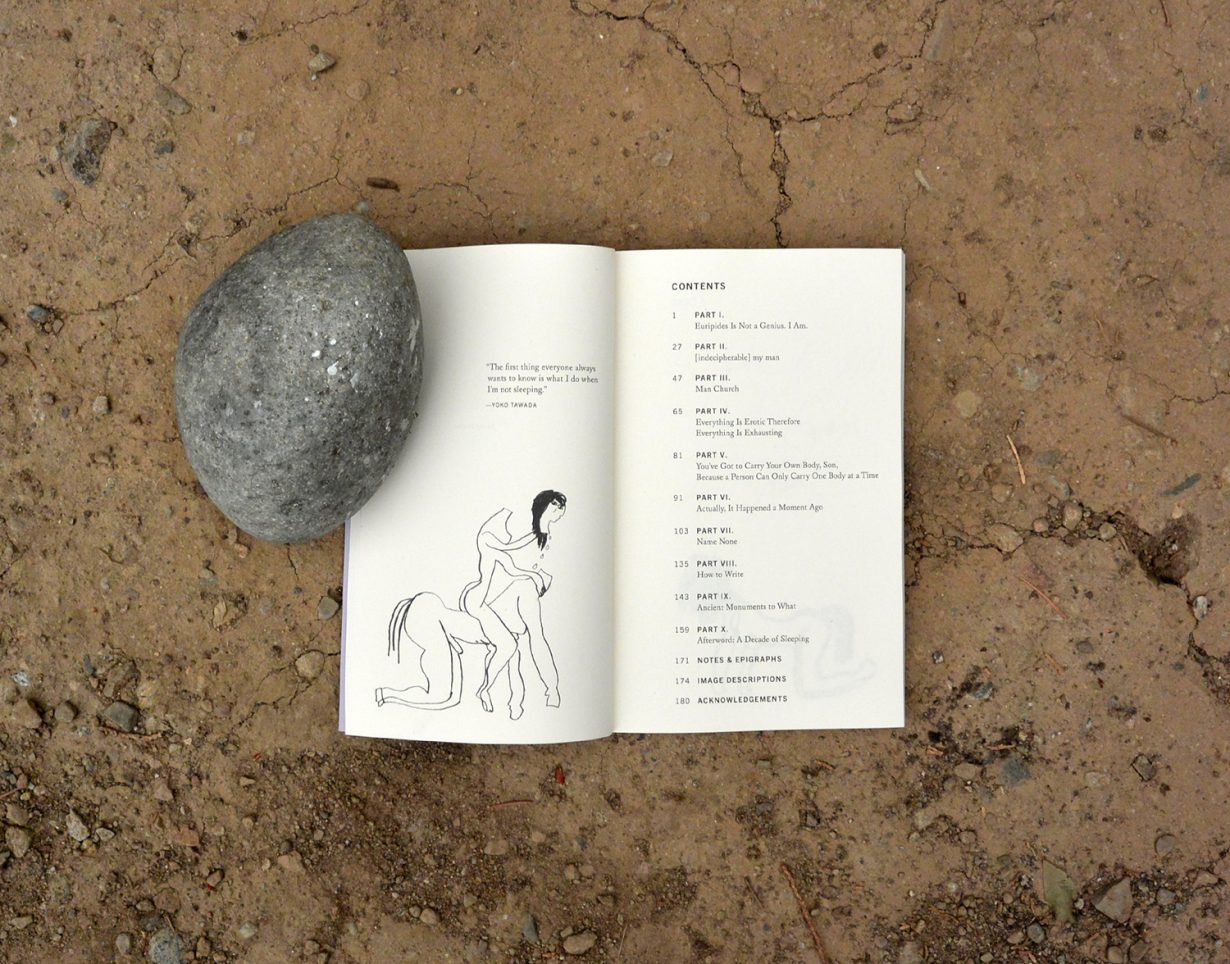

Hedva is also a writer who wades into prickly subjects: they court murderous rage, embody internet conspiracy and wax with blowjob poetry. Many of these forms are documented in their new collection, Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain (2020, Sming Sming Books), which includes drawings and documentation from performances. In 2016 they published a manifesto, ‘Sick Woman Theory’, in response to a chronic illness that prevented them from engaging in street protests, but offered a new kind of bedridden revolution. Other works include On Hell (2018), a paranoid, profane rant of a novel, and They’re Really Close to My Body (2020), a thoughtful ‘hagiography’ of Nine Inch Nails that treats the band as a kind of mystic saint.

Over the last few months, Hedva and I spoke multiple times over video chat for the ArtReview podcast Subject Object Verb. They were demonstrative and warm in these exchanges, laughing more often than their work would suggest. Soon after, we began a parallel exchange online, to capture the satisfyingly direct sting of their writing.

Illustrations by Isabelle Albuquerque. Courtesy Sming Sming Books

Ross Simonini Is there a philosophical perspective on death that feels most true to you?

Johanna Hedva Well, I’m a goth, so I’m partial to the ones who speak of death as the totalising divine. Georges Bataille, for whom God was death, comes to mind. I like [Eugene] Thacker’s book Cosmic Pessimism, it’s so emo.

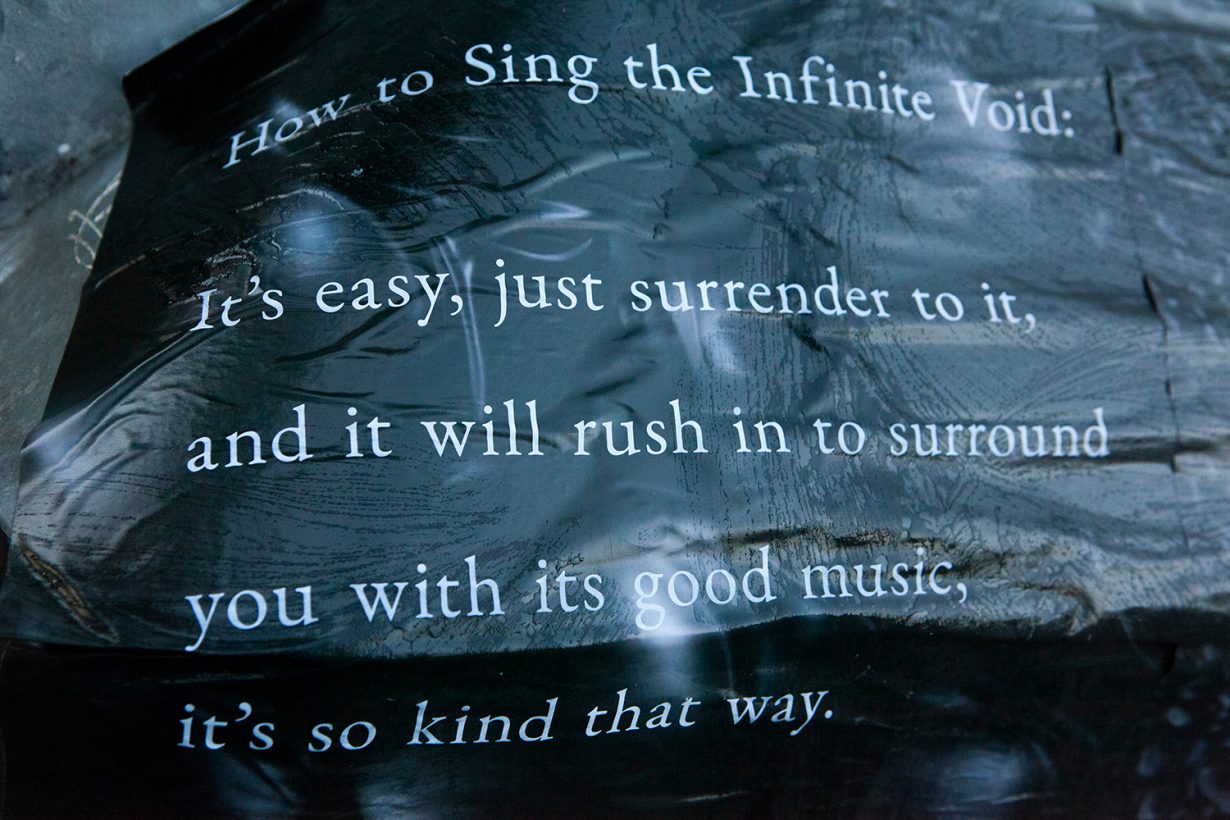

I spend probably an unhealthy amount of time thinking about the void. I’m pretty obsessed with black holes: black holes as a metaphor for death, and also as an un-metaphor, something so beyond language that it can’t be leveraged as a metaphor, feels very close. When I learned that black holes make noise, that when they collide it causes spacetime to ring, and that this is how we’ve been able to detect and articulate them – that nothingness sings – it made sense to me as a way to speak about death.

I was raised by witches, which means that the dead were very much alive in our house. They spoke constantly, and their language was tricky and multilingual, but they rarely spoke directly to you in a language you could understand. Sometimes they spoke in dreams, sometimes they turned the living room lamp on and off. I think any philosophy of death has to account for this, how the dead speak.

RS Were there any rituals, growing up with witches, that had an influence on you?

JH In a way, all of them did, but at the time, being a witch wasn’t popular or trendy like it is now. My mother and my aunt didn’t go around saying they were witches, and I didn’t tell anyone. It was a kind of kooky thing to have to go outside every full moon with your aunt to do a ceremony of pulling energy up from the earth and thanking the goddess. Or that my mother spoke to animals and named all her plants. At the time, it felt like growing up in any belief system: my mother’s family was Catholic, and my father’s family, who are Korean, were Buddhist, and the witchcraft and magic practices of my aunt and mother didn’t feel much different than these other religious practices. As an adult, I’ve come to my own spirituality and practice of mysticism, and I practice witchcraft. To me, being a witch means being in a respectful relationship with energies and forces and cycles of the natural and supernatural worlds, in particular the ones that can’t be seen or measured or explained by normative systems of meaning.

RS Do you have a preferred death ritual?

JH Living.

RS Did your family practice a specific tradition of witchcraft?

JH On my father’s side was the tradition of Korean fortune-telling. And my mother and aunt were working-class white women born and raised in LA, so I sometimes like to call them ‘sloppy Wiccans’, in that they weren’t formally initiated into any order, per se, but came to it through what was available to them at that time. This was the 1960s and 70s, so, for example, the books at their local witchy store would have been heavily influenced by Wicca, which was developed around the mid-twentieth century in England.

I think it’s important to point out here that most traditions of witchcraft have had to exist fugitively, through oral traditions passed down through generations, and the traditions can diverge greatly from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, family to family. For many, many, many years, one did not announce that one was a witch, for fear of actual persecution, so it had to be practised and kept alive in secret. It’s also true, for instance, that I’ve not had nearly as much access to my Korean heritage as I’ve had to the Eurocentric traditions, because, like most first- or second-generation Asian-American immigrants, that history has been lost to colonial migration and trauma.

part of I wanna be with you everywhere, 2019. Photo: Mengwen Cao

RS When you say that you’re a goth, what do you, personally, mean by that? Is it an identity?

JH I will refer to Leila Taylor’s Darkly: Black History and America’s Gothic Soul here. It’s one of my favourite books ever, I cannot recommend it enough. When I first read it, I just felt electrocuted with recognition. I agree with Taylor’s definition of goth as a sensibility and perspective on the world: she says it’s ‘the melodramatic élan to the dull hegemonic culture of positivity’, that it’s a dissent against a mainstream insistence on optimism, but specifically it’s very romantic and over-the-top about it. There’s always an overabundance with the gothic, in terms of emotion – it’s too much, too dramatic, too extreme, and I love that. It’s a refusal to just chill out and get over it. The gothic is devoted to the spectres and secrets of society that we’ve tried to repress – ghosts, haunted houses, the weird, the horrifying – and for Taylor, this is political. Darkly is about the social and cultural meanings of the gothic and goth, which is entangled for her personally as a Black goth. For Taylor, Blackness, especially in America, is core to the gothic, and Blackness is inherently gothic, and I think she’s absolutely right. Obviously I cannot relate because I’m not Black, but there was always something for me in being a goth that had to do with my being an outsider to whiteness and normativity, as a Korean- American queer person, as a disabled person.

RS Do you feel a part of a larger goth community?

JH Not really, but maybe that’s what makes me feel like a goth? Like, I’ve been wearing all black and probably too many capes since I was a kid – at age nine, I used to wander around my neighbourhood in a black cape, I obviously had no friends. I got made fun of and bullied endlessly at school, including by teachers, for what I wore (lots of burgundy velvet). I’ve never been part of any community of goths, but as an adult I would say that most of my friends were goths as kids, or still are. We clock each other in rooms, this ripple of recognition, like, hey, I saw you over there in your Rick Owens, wanna be friends? I think it’s a healthy subset of the queer community too – those of us who were goth loners and queer. Now that I’m older, I feel quite warm and loving toward younger goths, like when I see piles of goth kids sitting on the sidewalk smoking cloves, I’m like, awwwww yes you, keep writing that poetry!

RS What current goth artists are compelling to you?

JH Oh my god, so many. Obviously, the deity Diamanda Galás. Just. Everything. About. Her. Although she has explicitly said she’s not goth, but Greek, making a distinction in terms of the Germanic goths. M Lamar is an artist who detonates what’s possible. I am lucky that we’ve been able to play a couple shows together. His work constantly inspires me. Lingua Ignota is someone who I respect and admire immensely, and I love how she makes rage feel almost like wealth, that abundance of what is taboo in her work hits a gothic note for me. My dear friend Isabelle Albuquerque (who drew the illustrations for my book) just had her first solo show of sculpture open in LA, and there’s something a little goth in it for me, the sensuality that slips between the sexual and mystical. I’m a huge fan of Arthur Jafa, and I find his films to have some of this goth perspective that Taylor talks about, their dissent, their teemingness, in terms of Blackness.

RS I recently read Thomas Ligotti’s The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, which is a kind of history of pessimism, and I always find that philosophy of meaninglessness to be surprisingly uplifting.

JH I haven’t read Ligotti, but yes, I find meaninglessness totally liberating. That’s not to say I don’t believe in meaning, I just take great solace in how slippery it is. Meaning is always political, because when it gets bound up with institutions of power it is often used as a weapon, as a way to police. I guess, as someone who suffers because of such weapons, I tend toward the places where meaning is fugitive, exiled, banished, and the fact that it can shapeshift – that meaning is ultimately an invention, a costume that can be worn or taken off – is not just a consolation, but a strategy for how to think and live that helps me get by.

RS Another identity you’ve spoken about is that of the Sick Woman, which isn’t limited to gender or even illness. Since you wrote ‘Sick Woman Theory’, has your thinking around this identity evolved?

JH I proposed the Sick Woman as an identity that gets ascribed to anyone who is defined by care, by which I mean either that you work in care, or that you need it, and who doesn’t need it? (I don’t like the give/take binary in regards to care, because care doesn’t work like that, but anyway.) No matter your gender, if you are defined by care, you are feminised, rendered ‘weak’ and ‘vulnerable’, and devalued. The ‘sick’ part of the Sick Woman speaks to an identity that gets defined by ableism: if you are defined by the care you give and take, you are a person who is sick, or crazy, or unproductive, or a drain on resources, or dysfunctional, or disordered, or incurable, or worthless, etc, ad infinitum – in other words, your embodied existence deviates from ableist standards. Ableism is, to me, perhaps the most pernicious ideology, because it’s the very bedrock of how we decide whether a person is valued or not. White supremacy, racism, misogyny, transphobia, heteronormativity – all of these things need ableism in order to work because they are means of oppressing people based on an invented hierarchy of superiority and normativity.

I wrote ‘Sick Woman Theory’ five, six years ago, and at that time I was still new to disability justice work and its discourse, and to crip theory and politics. I’ve since been very blessed in finding my crip fam (they read ‘Sick Woman Theory’ and came and got me) and being educated by folks in the disability community who’ve been doing this work for years and years. They have given me a much deeper historical background than I had then, which is why elders are so fucking important in any kind of activism, and shown me how this work is not over. I hope that the essays I’ve written since then about illness and disability can document my passage through this learning and politic, and help others as they move through it. As any abolition work, any activism work, is, it’s a lifelong process.

RS In your essay on Nine Inch Nails guitarist Robin Finck, you write about your feelings toward him less like fandom and more like worship, or hagiography. What is the distinction for you?

JH In the process of writing that essay I came to understand that the difference between fandom and hagiography primarily has to do with the question of a devotion that is communal versus one that is solitary. Hagiography is the latter. And it is specifically about the writing of one’s devotion, which is an inherently isolated endeavour, and since it’s the writing of the life of someone divine (meaning they are probably dead), it’s doubly cloistered, because it’s an encounter with that which cannot be known. Fandom, for me, is earthly: you find out your favourite rock star’s favourite food, you learn the behind-the-scenes trivia of how your favourite movie was made and you commune with others to share the enthusiasm of this knowledge. Hagiography is otherworldly, unearthly. It’s that someone is unknowable, and hagiography is the writing into this mystery with the knowledge that it can never be known.

RS Are you interested in transforming yourself into someone worthy of hagiography?

JH I think that the transforming of myself into someone worthy of hagiography is the task of my would-be hagiographer.

Photo: Philipp Baumgarten

RS You’ve often mentioned mysticism as a part of your work and life. Do you see the act of creating art as a kind of mysticism?

JH I think it can be if you allow yourself to be annihilated in the process, which is what I try to do when I’m making things. All I’ve ever wanted to be is a humble servant to a craft. I think of mysticism as an attenuation of the self with nothingness, or with the divine (to me, those are often the same), and when things are really cooking creatively, that attenuation happens with the craft itself. It varies depending on the thing, of course: writing a sentence is like giving my entire purpose over to etymology, rhythm, grammar. Like, if I write a perfect sentence, it does not bring me glory. It brings glory to the sentence. Playing music is hella fucking mystical because it’s this annihilation of the self that happens within your body, and you can hear it vibrating through you. And then of course, when you perform live, that all just expands to include everyone in the room, all of their bodies and bones and souls and breath and the walls and ceiling of the room, all yoked together in this SOUND. Ugh, I really miss playing live, can you tell?

RS What about the experience of taking in art? Is that the same kind of experience for you?

JH Oh my god, yes. I am very hungry for that always, and maybe my threshold is low, or maybe I’m actually just dissociating, but I find it in many things. I’ve written about these mystical experiences of seeing live music in the Finck piece, and the Sunn O))) piece [‘A Vacuum Is Also a Plenum and Both Make Music Make Life’, artpractical.com, 2019] and the Lightning Bolt piece [‘The Mysticism of Mosh Pits, Or, The Mess of Sociality, Or, Have You Ever Seen Lightning Bolt Live?’, Third Rail Quarterly, March 2019], and I plan to one day turn that into a book. It happens for me in reading, in looking at paintings, in seeing performances. It happens maybe most frequently in movies, I am deep into movies, I watch a movie a day. Before COVID I went to the cinema all the time. Whenever I’m back in LA (I split my time between LA and Berlin), I stay with my aunt, who is walking distance from a Laemmle’s movie theatre, so I walk down there sometimes several days in a row to see everything they have. One of my favourite things is to go to movies alone. And one of my favourite experiences, just like in life, is that moment right after the trailers end, but the movie hasn’t started yet. Being in that huge dark room, in that moment of total blackness, and there’s this little breath of silence before the screen starts to glow.

Ross Simonini is an interdisciplinary artist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast, Subject Object Verb