The artist levels an ominous critique at middle-class America that feels less science-fictional than rational

More than 40 percent of Americans think that, in the next decade, a civil war is not only possible but likely, according to a 2022 poll. Josh Kline’s survey exhibition captures with clarity the inauspicious mood of recent American life. The exhibition’s title references a neoconservative, interventionist think tank supported by former vice president, and architect of the Iraq invasion, Dick Cheney. Assembling over a decade of Kline’s work – not-so-easily divided between pseudo-documentary videos, sculptures and new-media installation – the exhibition is literal, bleak and prescient. Historically bracketed by twinned financial crises – 2008’s bank failures and 2020’s pandemic-induced economic shocks – the show leaves little room for optimism. Yet these genre-eluding installations are not quite dystopian: Kline’s work, in a certain sense, comes across as more rational than science-fictional, which is perhaps the exhibition’s most disconcerting quality.

With the plush crush of mushroom-coloured carpet underfoot, Kline’s sculptural series Civil War (2016–17) offers visitors a near-future vision of middle-class America. Presented in one of the first galleries on the Whitney’s fifth floor (the exhibition continues on the museum’s eighth), it chimes an ominous tone for what’s to come. Piles of cast-concrete rubble, arranged like lunar debris, form small mountains of working-class relics. Cairns of commodities, those signifiers through which the working class demonstrates a sense of upward mobility, become the ruined aftermath of this speculative conflict. The piles consist, for example, of disintegrating symbols of commodity comfort: Shop-Vac pull-along vacuum cleaners, lawnmower parts and a sawhorse. Placed on the stage of domesticity, the kind of carpet to which my parents – a car salesman and nurse – aspired to in our suburban Maryland home, these relics hammer on a foreboding sense of future collapse. Kline offers visitors a diagnosis of frayed social fabric: the hollowing out and decay of mid-income stability.

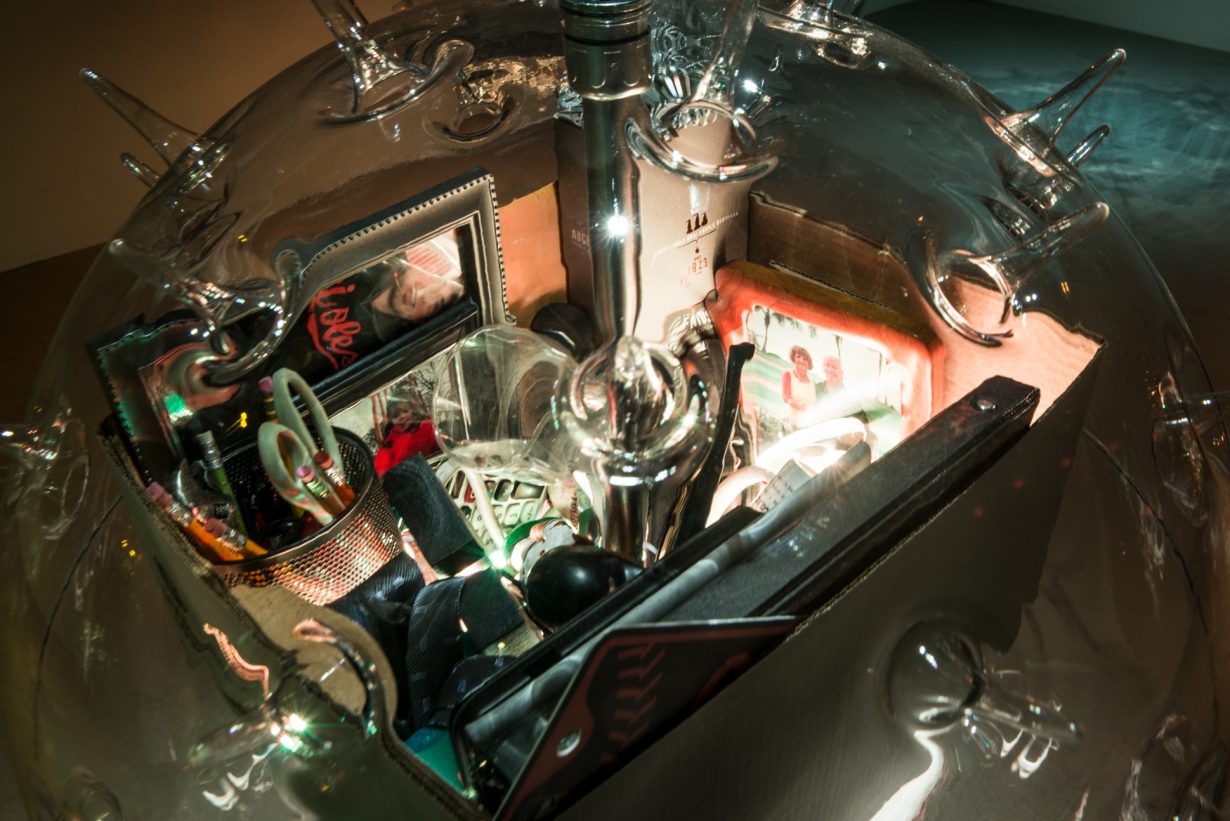

This vision of civil conflict becomes reframed as prescient after walking through Contagious Unemployment (2016). Inside clear plastic structures shaped like wriggling virus particles (the kind now etched into our post-COVID psyches) Kline has placed ‘bankers boxes’, cardboard archive boxes, stuffed with such white-collar office accoutrements as gym shoes, highlighters and family photos. Suspended from the ceiling at torso height, the works glow with the soft light of LEDs. Kline’s use of the virus visual is coincidental, sure, originally implemented as an allusion to the coming impact of automation on labour, according to the gallery’s wall text. The works have accrued an eerie aura about them in the years since 2020, undoubtedly reminding viewers of the mass layoffs that swept the world during the pandemic’s early days. In Kline’s future, the middle class is, and will continue to be, squashed, phased out, replaced.

In the context of America’s New York City, a gentrified metropolis rife with unequal wealth that has disconnected from the country’s heartland, Kline’s work emphasises the idea of class in a refreshing yet challenging – and even contradictory – fashion. What does an exhibition of art about workers’ plight mean at a privately funded museum, an institution funded by those who emerged the most unscathed (if not also the most enriched) from the financial calamities that historically frame Kline’s work? The easy, knee-jerk response could be that the institution swallows the critique whole. The exhibition’s central project is at odds with the privilege of the class that supports it. An inconvenient yet beguiling pairing indeed, especially at an institution once funded by a teargas mogul, an institution that only recently came to an agreement with its union, after 16 months of negotiations. On the other hand, might the Whitney Museum’s board be the ideal audience for this work, entreating it to seriously consider the future prospects of an increasingly shrinking middle-class and rapidly growing underclass? It seems unlikely that billionaires might yearn for democratic socialism, too.

In defiance of Postinternet labels, Kline’s new media-infused exhibition emphasises the very material consequences of what supposedly was a dematerialised era of the cloud and Web 2.0. For instance, Kline’s militarised Teletubbies are a funny, haunting take on the expansion of police surveillance. Po-Po and friends Courtesy, Professionalism and Respect (all 2015) are decked out in riot gear, handguns included. Kline face-swaps these mannequins with the queasy, androgynous facial features of the characters from that bizarre children’s television programme. Embedded in their torsos, little monitors play videos of real-life cops (whose faces are digitally swapped with those of activists) reading lines from the ‘found’ social media feeds of the featured activists, explains the work’s wall text. Kline has used face-swapping technology since at least 2013. Around the time of the exhibition’s opening, a deep-fake Drake song leaked onto the internet; pointing towards the obsolescence of technology often used in Kline’s art, but not the work itself.

Climate change, surveillance, AI, demographic shift in America: there are many profound threads to follow when discussing Kline’s survey. And here’s another: like the credits at the end of the film, Kline acknowledges the labour that produced his sculptures, featuring the names of his studio collaborators, mouldmakers and CNC specialists, among others, in the gallery labels. Ultimately a history that needs to and will be written about the role of specialised fabricators: MFAs with the minds of engineers, progenitors of DIY culture, unlikely to be rendered obsolete anytime soon, and who make the work of Kline, and the artists who show alongside him at New York’s 47 Canal, possible. They constitute a new working class that serves the gallery-going public. And, in tandem with their labour, Kline’s science-fictional art thus can become cinematic in scale, like a movie set that feels increasingly, unnervingly real.

Project for a New American Century at Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 23 August