The light festival of Saudi Arabia’s capital might sound a bit lacklustre or corny, but it did exactly what it set out to do: amuse, entertain and maybe even educate locals after a difficult year

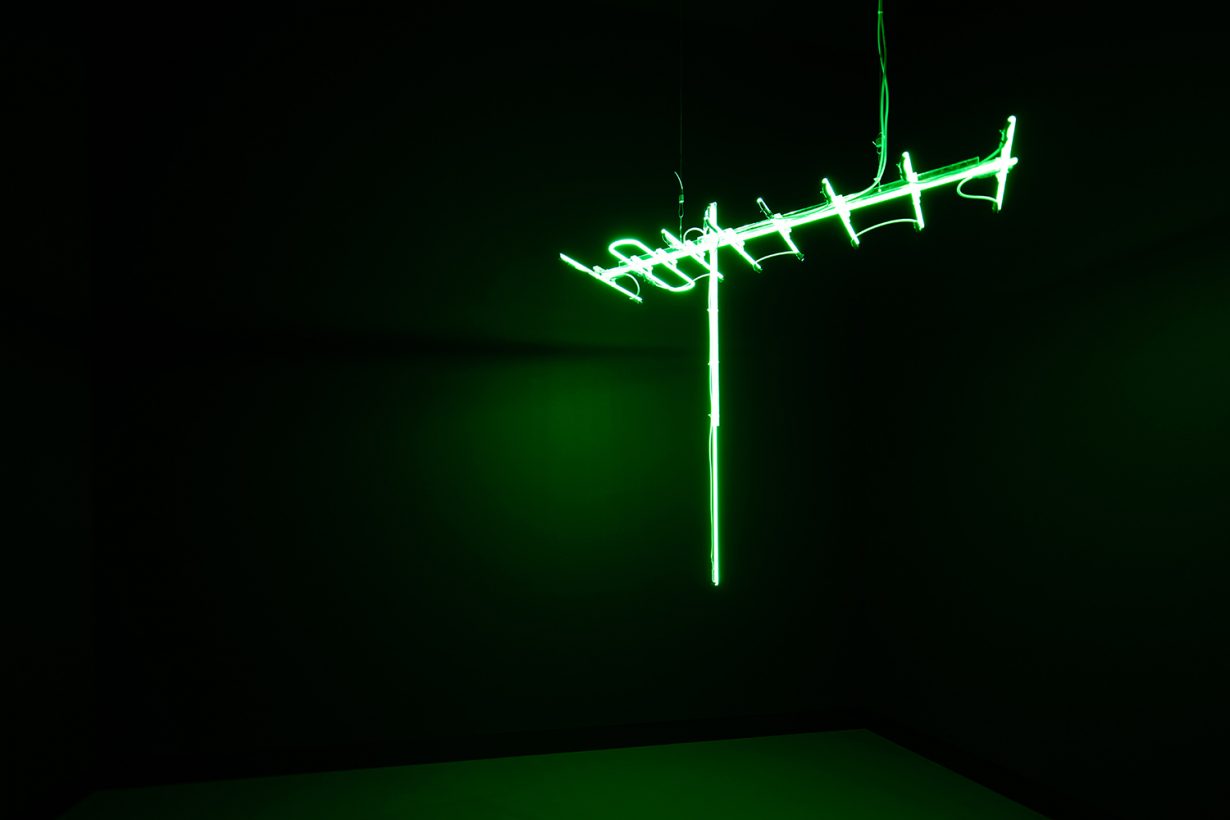

Light comes at you fast. In Rashed AlShashai’s kinetic sculpture Searching for Darkness (2021), crazily spinning lights describe a disarticulated conifer, a whirling dancer. In Abdullah AlOthman’s Casino AlRiyadh (2021), neon signage harkens back to a popular 1960s dinner spot in the Saudi capital as well as the embarrassment of creative, rather kooky signage that lights up the city. And in Ahmed Mater’s unshowy Antenna (Green) (2010), a neon aerial casts an acid-green glow. It’s a remembrance of the artist’s childhood in the southwestern mountain city of Abha, fiddling with the TV aerial to receive signals from nearby Yemen or Sudan, but it feels more like an antenna broadcasting the New Saudi Arabia to the world.

This is Light Upon Light: Light Art since the 1960s, part of the inaugural Noor Riyadh festival, which is in turn part of a recursive series of blueprints for the city’s and country’s future. There’s a heavy reliance on infinity mirrors in the exhibition too – including a Kusama room – most notably in Nasser Al Salem’s God Is Alive, He Shall Not Die (2012), in which a calligraphic ‘Allah’ is articulated in lights and reflected to repeat ad infinitum. I’m oddly moved. There are some of the Western greats of Light art too, including James Turrell, Mary Corse, Lucio Fontana, Dan Flavin and Robert Irwin. But the rather cramped temporary venue erected in a financial-district conference-centre largely dulls their effect, making the exhibition feel more like a glancing survey of ‘Light and No Space’ artists.

Outside, there’s a cluster of the monumental and light-based works that make up the citywide installations portion of the programme. Mostly bombastic and spectacular, they function as interactive entertainment and as an indexical map of Riyadh. Here is where you make money, here is a star precipitously suspended from the tallest building in the city, here’s an upscale megamall, here’s the tech hub, here’s the charming historical centre. Especially pointed is a Robert Wilson work that projects crashing waves onto the wind-eroded but magnificently conserved At-Turaif, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and – lest anyone forget – the birthplace of the House of Saud.

The light festival, which ended on 3 April, attracted some 310,000 visitors over its shortened two-week run – a smashing success in that respect. You might call the exhibition lacklustre and the light festival overproduced and a little corny – both criticisms are fair – but that’s beside the point. It did exactly what it set out to do: amuse, entertain and maybe even educate locals after a difficult year, with a little bonus razzledazzle for international viewers along the way. I was scandalised to find myself having fun at some installations, an all-too-rare experience. Attracting tourists? Maybe next year when borders are open and international travel is a go again. Artwashing? Most definitely, though none of the international participants seemed to care; one senses that that particular moment of sniffily performed refusal has given way to avarice-as-usual.

“What brings you here? Why are you interested in Saudi?” artist Muhannad Shono asks when I meet him one day. He’s one of scores of artists who have returned to Saudi in recent years, buoyed by the radical transformation of their country. He tells me about the whiplash cognitive dissonance of seeing these shifts happen nearly overnight, and after we speak I notice it too, the young Saudis dating, holding hands on the streets, things not coming to a standstill during the call to prayer. And he tells me about an unnamed French curator who remarked, in peevish response to the changes, “What will we write about now? It will be boring if it becomes normal like Europe.”

As for his question, I still don’t know how to respond. In my hometown of Dubai, to which I’ve just returned, the answer would be easy: following the money. Noor Riyadh comes under the umbrella of Riyadh Art, whose mandate includes ten ‘pillars’ (or artistic programmes) and a thousand works of public sculpture across the city’s parks, squares and under-construction public transit system; gallerists are expanding their programmes accordingly. The numbers seem designed to scale, from consultant-produced PowerPoint to press release. It has also been retrofitted to include the city’s annual sculpture symposium, now in its third year. Riyadh Art is itself a pillar – a favourite word there – of the Royal Commission of Riyadh under ‘Vision 2030’, MBS’s blueprint to diversify the economy away from oil (one wonders about the energy consumption of all this lighting), attract tourists and improve the quality of life, mostly through ‘gigaprojects’.

Outside this structure, the Diriyah Gate Development Authority has turned an industrial area into the art-and-culture district JAX, which hosts some of the Noor Riyadh installations – among them Shono’s sprawling light and disconcertingly mossy steel-wool affair – artist studios and the kinds of shops and restaurants that lure people who self-identify as ‘creatives’. The artist adopted a stray dog he found in the area and named it Jax; Vice Arabia is already set to move in. In December, JAX will host the first iteration of a contemporary art biennial curated by UCCA’s Beijing-based Philip Tinari and featuring around 70 mostly non-Saudi artists. Double digits of heritage and art museums, and an intersection-of-art-and-tech oasis, are on their way. The Misk Art Institute is in the mix too. Whereas Misk once used to function like Mater’s Antenna, amplifying Saudi art in the wider world as an extension of the Edge of Arabia initiative (launched in 2003 to foster cultural dialogue between Saudi Arabia and the rest of the world), it has now shifted focus to emphasise programming, pedagogy and artist development, including generous grants and residency programmes. And that’s to say nothing of developments in other cities like Dhahran and Jeddah.

The most interesting part of all of this cultural infrastructure is that they aren’t merely trying to turn out artists and curators – or worse, critics – but fabricators, lighting technicians and art handlers too. “You’ll never see an Emirati or a Qatari working as a mover,” one of the festival directors explains, emphasising KSA’s demographics. Unlike its neighbours, the population of Saudi Arabia is majority Saudi and doesn’t have the luxury of reserving the prestige jobs for its own citizens while importing foreign labour to pick up the more menial slack. Equally encouraging is hearing that these foreign executives and consultants on the Gulf art circuit – most initially landed in Doha, with stints in the UAE before moving to Saudi – expect to be in Riyadh for only three to five years before moving on and handing the reins over to local teams, unlike somewhere like Dubai where they might expect to be installed for life.

Riyadh confuses me. Though it is my first visit, everything about it feels so familiar, too familiar. But instead of the ever-present humidity and coastal tang that inextricably denote a Khaleeji city for me, the air is dry enough to give you razor burn. The seven-million-strong capital has a much more robust public life, despite the even hotter climes, and a dynamic – if rough around the edges – big-city energy. A major plank of future development is aggressive greening, but the water table has been exhausted, so seawater is currently piped from the Arabian Gulf inland to Riyadh, where it is desalinated. When I visit the wadis (the rivers, as opposed to dry beds, on whose banks the city developed) on the outskirts of the city, where ducks have adopted a UxU Studio installation as a potential nesting ground, seeing these water bodies where settlements originally sprung up makes the land make more sense, though it still feels like an ecological disaster in the making. Everything is under construction, and the traffic barriers are draped with strip lights that look like illuminated ice cream drips. The atmosphere feels so electric – a wild energy that has nothing to do with the installations – that I find myself thinking I could move there.

I find myself thinking about this when I return to visit some of my favourite works, which are all clustered around a lovely old park. I find myself again unexpectedly moved by the way that residents seem to find both pleasure and solace under and around the installations. Quietly stunning is a VOUW work that shows the spatial expansion, and by extension increased light pollution, of the city itself. Suspended above a patch of grass, it’s a time-lapsed map of Riyadh that begins with a single lit-up square, the historical centre where it’s installed, and expands outwards as the city sprawls. I’m surprised to hear Urdu, then Tagalog, in Marwah Almugait’s video, projected onto a mist-and-water screen, and delight in the simple pleasure of Saeed Gamhawi’s carpets projected onto sand to form a plan of his mother’s house. And in Ayman Zedani’s trio of carmine-tinted climate-fiction films, the near future that plays out on each screen is obstructed by date palm trunks and, fittingly, pillars.

Noor Riyadh, various venues, Riyadh, 18 March – 3 April 2021