Man, Bird and Tree at Carl Freedman Gallery, Margate provides a welcome reminder of a superlative colourist and storyteller of postwar British painting

Since his death in 2001, it has remained difficult to fix Ken Kiff’s place in the firmament of postwar British painting. A superlative colourist, who employed his pigments not as ornamentation but as the foundation of pictorial structure, he was also a beguiling visual storyteller, relating oddly affecting Jungian fables that appear to have emerged from his own private mythology. Like his lodestar Marc Chagall, Kiff had no use for angst, or macho painterly grandeur. Rather, as this welcome showcase demonstrates, he was an artist who above all essayed tenderness, nurturing the surfaces of his paintings into dreamy, almost psychedelically chromatic visions in which compassion was the whole of the law.

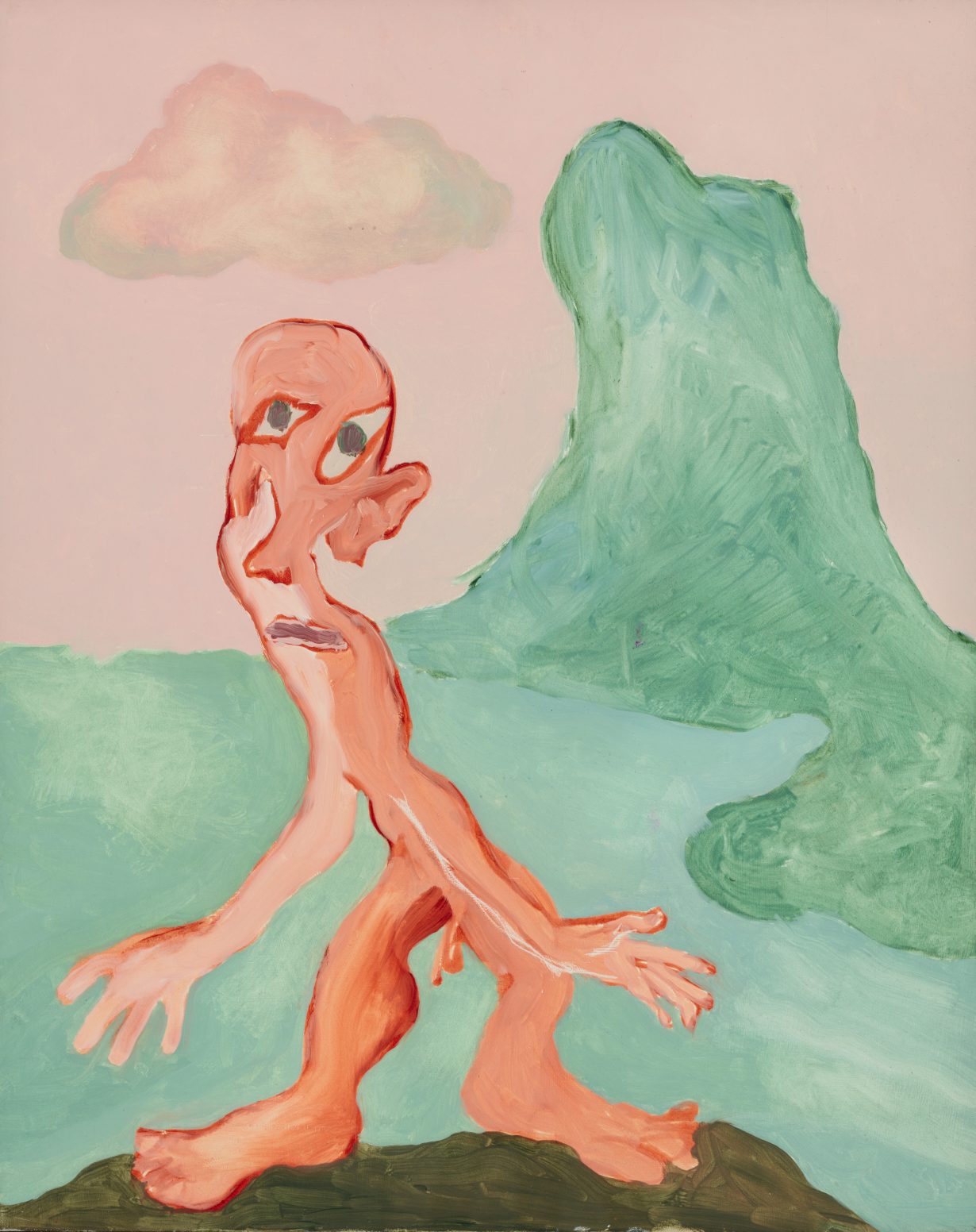

Central to Kiff ’s project was the ‘Little Man’, a recurring naked, baldheaded figure whom the artist’s great champion, the late critic Norbert Lynton, described in a 1988 catalogue essay as ‘[Kiff ] himself, a pilgrim making his way through the world’. In the painting Man and Island (1987), we see this diminutive dude stranded on a barren rock, both its sovereign and its sole, lonely resident, his pink, weirdly pliable body resembling a piece of bubblegum spat out by an uncaring god. He reappears in There was an immense laughing rat (1977), assailed by a smirking rodent as he flails and splutters in a choppy sea, and again in Man, Bird and Tree (1987), where he gingerly approaches the nest of a blue duck, perhaps to steal its eggs, all the while observed by an ineffably smiling sun and a great, unblinking eye on a purple stalk. Beset by forces beyond his control, not least his own nagging drives, he is part Prometheus, part Job and wholly sympathetic.

Kiff’s female figures are, by contrast, much more elemental: water nymphs, earth goddesses, flaming orange angels. Does this speak of reverence, or the limits of the artist’s imagination? Kiff was undoubtedly at his best when figuring men. Amazement (c. 1970s) depicts his little proxy caught in a moment of grinning, goggle-eyed rapture, although what’s triggered this (an external event, a sudden internal awakening?) is left to our imaginations. His expression is daft, yes, but also irresistibly infectious. This painting is, in its own way, miraculous: an image of masculine vulnerability suffused with carefree joy.

Man, Bird and Tree at Carl Freedman Gallery, Margate, through 5 February